Obligation-based Theory vs. Right-based Theory: Confrontation of Ideas Between Warrender and Strauss

TANG Xueliang*

Abstract: There is a transition from the objective laws or moral orders that precede human will in classical natural law to the subjective demands or rights emanating from human will in modern natural law, and it represents a historical debate on the shift from an obligation-based theory to a right-based theory. Strauss, within the context of this transition across time, assesses Thomas Hobbes’s philosophy of law and recognizes him as the founder of modern natural rights theory. Using Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld’s analysis of jurisprudence, Howard Warrender assesses the privilege nature of Hobbes’s concept of natural rights and concludes that, since Hohfeld’s privilege is the opposite of obligation and related to no-right, obligations cannot be derived from natural rights. Therefore, Warrender argues that Strauss’s assertion requires correction. However, Warrender places excessive emphasis on Hohfeld’s static separation of the concept of privilege within his theoretical system, overlooking the dynamic transformation from privilege to claim rights. In this regard, Hobbesian scholar Carlan’s criticism of Warrender is valid. Meanwhile, Warrender’s research holds theoretical significance in that he, under the premise of being a part of Hobbes’ natural law tradition, transforms Hohfeld’s flat, two-party legal rights relationships into a three-party legal rights structure, which could represent a potential innovation in the 20th century legal philosophy.

Keywords: obligation · nature rights · privilege · Warrender · Strauss

Strauss’s discussion of Hobbes is well known in Chinese academic circles. To put it simply, Strauss reads Hobbes’s philosophy of right in the light of “the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns” — the distinction between the traditional natural law that is an objective rule and measure, a binding order prior to the human will, and the modern natural law that is a series of rights of subjective claims originating in the human will, and then recognizes him as the founder of modern political philosophy. This is to say, in Strauss’s view, Hobbes was the first to make the shift from the classical philosophy of duties (or obligations) to the modern philosophy of rights. The so-called foundation of modern political philosophy is essentially the foundation of modern theories of rights. Warrender, on the other hand, in his famous book, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, explicitly presents the traditional view of Hobbes’s theory of obligation. On the face of it, Warrender makes it clear that of all the publications he has benefited the most from are the works of Oakeshott and Taylor. Strauss’s name appears only five times in the footnotes, and there is no mention of Strauss in the text of the book. And more importantly, in three of these five footnotes, Strauss does not appear as the lead author. Even so, a close reader of this Warrender book can read between the lines and see Strauss.

Any dialogue between scholars is based on the strict demarcation of concepts and categories. Before the dialogue with Strauss, Warrender had already prepared his own conceptual toolbox, that is, his digestion and absorption of the Oxford School of ordinary language philosophy (or the Oxford philosophy), or more directly, Hohfeld’s analysis of jurisprudence. On this basis, he conducted a profound criticism of Strauss’s modern right theory.

I. Warrender’s Application of the Hohfeldian Analysis

A. Hohfeld’s theory of rights

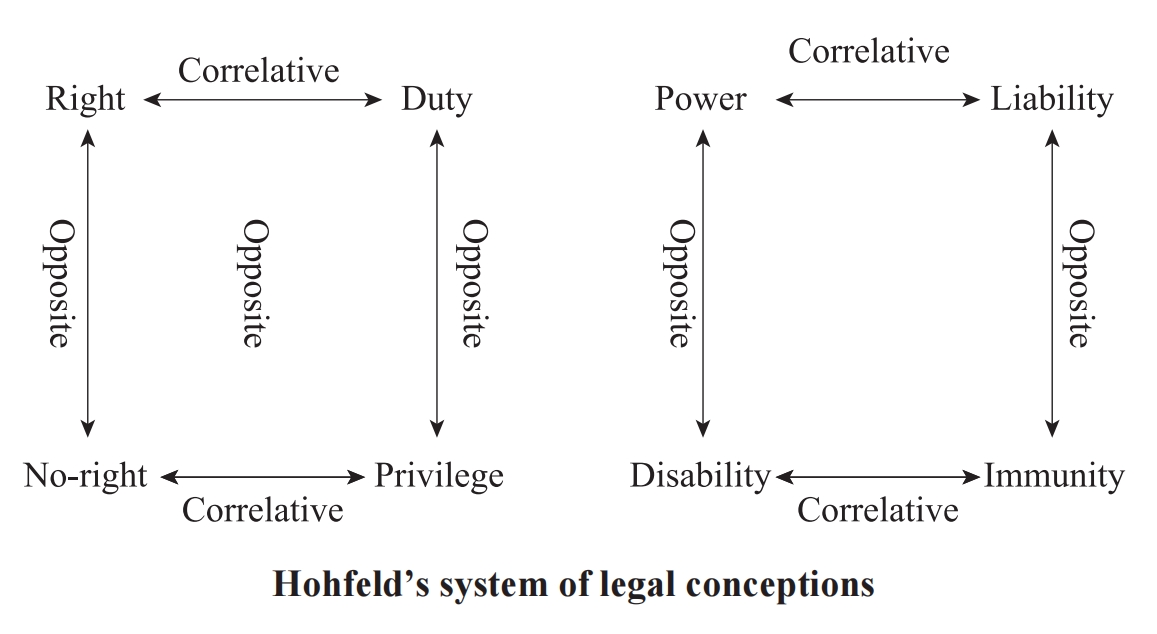

Before discussing Warrender’s conceptual toolbox, it’s worth a quick overview of Hohfeld’s jurisprudence or analysis of legal rights. Based on the studies of Bentham, Austin, Gray and others, Hohfeld first proposed eight basic conceptions as the “lowest common denominators” for the analysis of all legal relations. For a closed logic, he further divided the legal relations into correlative and opposite relations,1 as shown in the figure below.

In the above figure, “right” (in the narrower sense), “privilege”, “power” and “immunity” are the different interpretations of right in the wider sense, namely, we mean in daily life in different situations and relations. They are collectively referred to as legal interests or benefits, while “duty”, “no-right”, “disability” and “liability” are collectively referred to as legal burdens or ligations. So how to understand the connotations of these conceptions? Based on the examples or instances given by Hohfeld on different occasions, we can illustrate them with a simple ownership relation. Assuming that Person X has complete ownership of Land A, Y, the other person, has a duty not to enter the land; X has a right or claim that Y should stay off the land, and such claim is also a concept of right in the narrower sense mentioned above. In the opposite case, X has no-right to enter. So, one’s right (or claim) is the correlative of the other person’s duty and is the opposite of his own no-right. In the meantime, as X himself has the privilege of entering Land A; or, in other words, X does not have a duty to stay off, and Y has no-right to ask X to stay off. So, one’s privilege is the correlative of the other person’s no-right and is the opposite of his own duty. If X makes an offer to Y to sell the land, then Y has the power to change the ownership relation of Land A by undertaking, and X must bear the related liability; otherwise, Y is under a disability (i.e., has no power) to change the legal relation, and X shall enjoy a corresponding immunity, that is, the freedom from Y’s legal power. The essence of these conceptions can be roughly clarified through a simple ownership relation, but the complexity lies precisely in the conception of “privilege”, which is particularly addressed in this paper. As a civil law scholar stated, “privilege is the most intricate but most important conception in Hohfeld’s theory.”2

To Hobbes, right, especially natural right (or right of nature), is basically equivalent to liberty: “Right consisteth in liberty to do or to forbear.”3 “The right of nature, which writers commonly call jus naturale, is the liberty each man hath to use his own power as he will himself or the preservation of his own nature.”4 Hohfeld also regards right in the sense of privilege as liberty: “The closest synonym of legal ‘privilege’ seems to be legal ‘liberty’.”5 But on closer examination, there are slight differences between the two conceptions. Hohfeld once distinguished them using Gray’s upsetting shrimp salad example, roughly as follows. A, B, C, and D, being the owners of the salad, might say to X: “Eat the salad, if you can; you have our license to do so, but we don’t agree not to interfere with you.”6 In this case, we might say X has the privilege of eating the salad, so that if X succeeds in eating the salad, he has violated no rights of any of the parties. But X does not have the right to ask the owners of the salad not to interfere with his eating of the salad. Even if they had succeeded in putting the salad somewhere where X couldn’t eat the salad, no right of X would have been violated. That is, they are under no obligation or duty to serve X the salad; in terms of right discourse, they have a privilege of not letting X eat the salad. It follows that there may be two privileges which are the opposites of each other in the same matter. This shows the subtle distinction between privilege and liberty, because a liberty in general is often accompanied by a claim right, at least a claim right that the other party does not interfere; otherwise, such liberty may be meaningless. But in strict judicial reasoning, privilege is not like this. Thus, one important distinction between them is that liberties are often guaranteed while privileges are not. However, for Hobbes and Hohfeld, a liberty obviously does not come with a claim right, but is a natural liberty without a duty or obligation. Although both liberty and privilege can be expressed with no-duty, “the term ‘privilege’ is the most appropriate and satisfactory to designate the mere negation of duty.”7

B. Warrender’s acceptance of Hohfeld’s theory of rights

In the research community, a Hobbesian right, especially the natural right, is often interpreted as liberty or privilege. In this regard, Warrender was the initiator. Warrender stated, “Hobbes uses the term right with two distinct meanings: (1) as that to which one is morally entitled; (2) as that which one cannot be obliged to renounce.” He also believes the latter sense was more common for Hobbes and of greater philosophical significance. The rights in the former sense are merely the shadows cast by duties, while the rights in the latter sense are the opposites of duties.8 This paradigm seems to dominate later Hobbesian studies. According to Gauthier, Hobbes’s natural right indicates something that an individual can do, but does not indicate any claim right on others; and the natural right is not a correlative of a related duty.9 Kavka also argued that natural rights are fundamental rights in Hobbes’s system. Like Gauthier, he explicates such rights as permissions, which are not the correlatives of the duties of others.10 Hampton makes it clear that Hobbes’s right is a privilege or a liberty, and is the opposite of a duty. “If I have a liberty to use land in a certain way, I may do so or not, as I desire.”11 It also means that other people have no right to claim whether “I” do so or not. More recently, scholars represented by Zagorin believe that “Hobbesian natural right and a certain idea of freedom are interwoven.”12 Keen readers may see that while these authors, with the exception of Hampton, do not directly mention Hohfeld by name in their respective texts or references, this paradigm of rights research has undoubtedly been greatly influenced by Hohfeld, directly or indirectly. Warrender is no exception.

In the 20th century, philosophy went through the so-called “linguistic turn”; and at the time of Warrender’s study at Oxford, the ordinary language school or “Oxford school” of philosophy was at its heyday. In addition, in terms of personal interactions, Warrender was very close to J. L. Austin, the leader of the Oxford ordinary language philosophy. In the preface of The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, he clearly stated, “More immediately, I am indebted to Prof. J. L. Austin, Prof. W. G. Maclagan, and Mr. W. Harrison for reading through my manuscript, and should like to express my gratitude for their valuable advice and criticism.”13 Based on Warrender’s academic background and his familiarity with the legal theorist Austin and legal positivism shown in his works, it is reasonable to assume that he must also be familiar with Hohfeld’s analysis of jurisprudence. And more importantly, from Warrender’s analysis of Hobbesian rights, we can clearly feel the strong presence of the Hohfeldian analysis of rights. For example, Warrender defines a right “as that which one cannot be obliged to renounce”;14 for example, in Hohfeld’s system of conceptions, privileges can only be denied, not transferred, because they are negative rights; while Warrender also stated, a natural right could only be a possible liberty, freedom from obligation, so that in a strict sense, it would be meaningless to discuss the transfer of a natural right;15 for another example, when discussing the authorization of the sovereign and his rights, Warrender stated that this might mean it also requires “active cooperation from the citizen in addition to the privileged action of the sovereign”,16 where Warrender directly uses Hohfeld’s conception of privilege. All of this shows that Warrender was deeply influenced by Hohfeld’s analysis of rights; it may be that he did not mention Hohfeld directly because of factors such as academic citation habits at the time. Based on the demarcation of conceptions, Warrender launched a serious ideological debate with Strauss.

II. Confrontation of Ideas Between Warrender and Strauss

A. Debate on rights-based and duty-based systems

Strauss’s interest in Hobbes continued throughout his academic career, during which, except for some adjustments on some individual issues such as Hobbes’s positioning and the relationship between political science and natural science, his basic views remained the same, which are mainly demonstrated in his early publication The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. The book contains a preface (including a new preface in the American edition) and eight chapters. In the preface, Strauss goes right to the point and makes an argument about the change from traditional to modern natural law, that is: “Traditional natural law is primarily and mainly an objective ‘rule and measure’, a binding order prior to, and independent of, the human will, while modern natural law is, or tends to be, primary and mainly a series of ‘rights’, of subjective claims, originating in the human will.”17 This passage is the highlight of the book, initiating Strauss’s awareness of “the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns” that lasted throughout his life. On this basis, Hobbes is measured within the framework of such a larger paradigm shift. “For Hobbes obviously starts, not, as the great tradition did, from natural ‘law’, i.e., from an objective order, but from natural ‘right’, i.e., from an absolutely justified subjective claim which, far from being dependent on any previous law, order, or obligation, is itself the origin of all law, order, or obligation.”18 In this way, Hobbes’s science of politics, unlike either the idealistic objective moral order or the purely natural desire, lies somewhere in between. Strauss believes that there is a huge obstacle to understanding this intermediate nature, which is the attempt to base Hobbes’s political philosophy on the modern science of nature. In fact, this obstacle not only comes from the analogies to tradition that are habitually used in academic circles, but also from Hobbes’s own self-declaration of his philosophical trilogy. However, Strauss believes that such analogies are destined to be confusing, because modern metaphysics, unlike traditional metaphysics, is not teleological. Thus, it is impossible to use the conceptions of modern natural science to understand people and their moral and political life, or to distinguish the relations between “rights” and pure natural desires. Strauss, accepting Robertson’s view,19 believes that Hobbes’s principle of rights is based on a unique outlook on life and moral attitude, and the acquisition of such outlook on life and moral attitude is the result of Hobbes’s acquaintance with traditional and modern science. Therefore, it will more accurately grasp his unique outlook on life and moral attitude if the process of such acquaintance is included in Hobbes’s system, especially the early works, for comparison and examination. In this regard, Strauss spends about four chapters, focusing on Hobbes’s educational background, professional experience, and early translation history as well as the system of his works, to deliberately explore and interpret the “new moral attitude” as the substance of Hobbes’s political science. This new moral attitude, in form, is the replacement of aristocratic virtue by middle-class virtue. In essence, it is a new view of passion. This ideological journey confirms Strauss’s argument earlier in his book that the real foundation of Hobbes’s political philosophy is not natural science, but the theory of human nature, which can be summed up as “two most certain postulates of human nature”, or, the opposition between two outlooks on life: one is vanity (or vain conceit), which is the root of natural appetite; the other is the fear of violent death, which is the passion that awakens people’s reason. The former is the ultimate cause of injustice, while the latter is the ultimate cause of all justice and morality.

This may not mean much if it is merely to reveal Hobbes’s morality, because every era and even every person has their own moral values, and why should Hobbes’s moral philosophy be so worth reading and writing about? Strauss further states: “Not the moral attitude itself, but the unfolding of its universal significance, of the whole nexus of its presuppositions and consequences, is the result of the genesis of Hobbes’s political philosophy.”20 The “universal significance” may be reflected in two aspects: the significance to Hobbes’s political philosophy, and the significance to political philosophy itself or the ancient and modern political philosophies. As far as the former is concerned, moral attitude is only the material or substance of Hobbes’s political philosophy, which must be combined with the methods of natural science to make Hobbes’ political science. In this regard, Strauss lacked an in-depth understanding of it both in The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis and in his later studies. The reason is not only that Strauss failed to grasp the connotation of Hobbes’s metaphysics,21 but also that he simply equated Hobbes’s natural science with analysis and synthesis as scientific methods. This only received a coherent and systematic explanation from the French scholar Zarka.22 The latter, that is, the “new political science” created by Hobbes and the consequent quarrel between the ancients and the moderns, is the focus of Strauss. “According to Hobbes, the basis of morals and politics is not the ‘law of nature’, i.e., natural obligation, but the ‘right of nature’. The ‘law of nature’ owes all its dignity simply to the circumstance that it is the necessary consequence of the ‘right of nature’. It is from this standpoint that we can best recognize the anti-thesis between Hobbes on the one hand, and the whole tradition founded by Plato and Aristotle on the other, and therewith at the same time the epoch-making significance of Hobbes’s political philosophy.”23

If the “universal significance” is regarded as the foundation of philosophy, then Strauss’s demarcation of Hobbes’s moral outlook on life has only instrumental significance. The real teaching it wants to convey is the change from the duty-based theory to the rights-based theory in ancient and modern times. If Hobbes were to be understood in this way, the book might be better titled The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Theory of Rights than The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis. Warrender, on the contrary, believes that obligation is the core theme of Hobbes’s moral and political philosophy, and that this obligation runs through the entire process from the state of nature to political society. As can be seen from the previous assessment, for Hobbes, the typical use of right does not refer to a person’s entitlement to something (the right to do it or have it), but that a person is under no obligation to give up doing it or having it. If this is the case, then Hobbes’s right, like Hohfeld’s privilege, is not connected with the obligation of the person to whom the right is directed, but is only the result of logical or empirical analysis of the obligations. For example, the right to life does not refer to the right to claim against others, but only that a person is under no obligation to give up his life. This does not mean that others cannot kill him for some reason. And of course he is not obliged to yield without a fight when others do so.24 Just like the Salad Case mentioned above, can such a conception of right in the sense of privilege support Strauss’s argument? If translated into the Hohfeldian terminology, Strauss’s right is more of a right in the sense of a claim or in the true sense of right. So Curran, who specializes in scholarly research on Hobbes’s works and opposes the interpretation of Hobbes’s concept of right using the Hohfeldian privilege, sees Strauss as a fellow.25 That’s why Warrender also stated: “(Hobbes) he has tended to be taken as the father of modern political philosophy in basing his defence of the State upon rights; or, for example, he has been held to deduce obligations from his ‘right of nature’. Such estimates, however, are in need of revision.”26. Although Warrender does not mention Strauss by name in the text or in the footnotes, it is obvious to a discerning reader that he is talking about Strauss. The reason why Warrender makes this argument is that the “right” in the first proposition generally refers to substantive entitlement or claim, which is obviously not the case with Hobbes’s conception of right. As for the latter proposition, it is a logical paradox. For if a right implies immunity from a duty or obligation, then just as existence cannot be founded on nothing, a duty cannot be founded on no-duty. Thus, Strauss’s “estimates are in need of revision”, actually means Strauss’s The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Theory of Rights should be revised to Warrender’s The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation. Of course, whether Warrender’s argument holds up will be further analyzed as follows.

It is also worth noting that Warrender’s denial of Strauss’s theory of converting right does not mean that he thinks the natural rights theory is meaningless, as he stated that it is not meaningless to regard a purely formal principle as constituting a natural right,27 and that “the validating conditions of law prescribe by negative inference the circumstances in which obligations to God or man can have no place, and therefore in which blame and punishment can have no place. They may be taken, either as the minimum statement and perhaps the only justifiable statement of a theory of natural rights, or as a beginning in the analysis of the terms of ‘obligation’ and ‘law’. To this extent, Hobbes’s theory of right is more fundamental than his theory of duty.”28 So, from this perspective, Strauss’s argument still holds true, but we need to be vigilant about it. This is not only because their conceptions of “right” are largely different from each other, but also because duty or obligation is the primary conception of Hobbes’s philosophical system, with rights being the result of its analysis.

B. Debate on the source of obligation

As mentioned above, unlike Strauss, Warrender believes that the basis of Hobbes’s philosophy was not the right as a privilege, but the obligation. In order to advance the study on Hobbes’s theory of obligation, first, Warrender demarcated the meaning of the term obligation. He opposed Oakeshott’s concept of rational ob ligation, and believed that, for Hobbes, there were only physical and moral obligations, and physical obligations were more of a rhetoric and played almost no role in Hobbes’s philosophy. Then, Warrender activated and developed Hobbes’s theory of obligation into a system with several core conceptions, which include: the grounds of obligation, the validating conditions of obligation, and the instruments of obligation. Through these conceptions, Warrender was able to reveal some relations that seem ambiguous or even obscured. The so-called ground of obligation refers to the source of establishing an obligation. Because it is somewhat speculative, Warrender discussed it in the last part of his book. And he said that even if his explanation is untenable, it does not affect the understanding of the theory of obligation itself. The conceptions Warrender focused on are the validating conditions and the instruments of obligation. The validating conditions of obligation refer to the conditions that must be satisfied for a ground of obligation to function or be operative. They specify the class of persons who incur obligations, such as sanity and maturity. Therefore, if expressed negatively, they will be called invalidating principles. For if a person has a mental illness or not an adult, then he does not bear the obligation. In Hobbes’s theory, the validating conditions of obligation mainly include: first, an individual must be able to know the law; second, the individual must be capable of having a sufficient motive to obey the law, which is also the principle of “Ought Implies Can”. These two conditions are logically deduced based on Hobbes’ conception of obligation; but for the motive involved in a specific action, it must be supplemented by Hobbes’s psychological principles that have been reflected on experience. For example, according to this hypothesis, an individual may not be capable of having a sufficient motive to kill himself, and such.29

If readers have not forgotten the above Hobbes’s concept of right, then we can deduce that the validating conditions of obligation are actually an expression of right, and that the absence of validating conditions also means that a person enjoys freedom from obligation, that is, he enjoys a certain right. Thus, we can see that, Warrender, unlike Strauss who takes right as the fundamental concept of Hobbes’s philosophy, tries to see right under the conceptual structure of the validating conditions of obligation. But when we say this, we do not mean that the concept of right can be completely covered by the concept of obligation. Because as Warrender said, from the catalog of obligations we can only infer what is not an obligation, but not what cannot be an obligation. From the negative inference of the concept of right, we can only get what may be an obligation but not what is an obligation. Therefore, in Warrender’s eyes, Hobbes, in addition to proposing a theory of obligation on which one would be obliged to do something, also proposes a theory of obligation on which one is not obliged to do something. This complete theory of obligation is not only the basis for understanding Hobbes’s philosophy, but also his unique contribution to political philosophy.30 If viewed in this way, then Hobbes’s philosophy is still a philosophy of obligation rather than a philosophy of rights as claimed by Strauss. The instruments of obligation are the standard means to incur obligations, and they answer the question of how rather than why we are obliged. In Hobbes’s system, the sole means to incur obligations are laws that passively impose obligations upon a person and covenants by which a person actively takes obligations upon himself or herself. Since laws and covenants are the means to incur obligations, if the laws or covenants are invalid, there will naturally be no corresponding obligations. Hence, in this sense, the validating conditions of laws or covenants also become the validating conditions of obligation. This means that they can also be transformed into the rights discourse.

Hobbes is usually regarded as a contractarian philosopher, which shows the important position of contract in his philosophical system. Naturally, contract is also one of the focuses of Warrender’s research. Warrender took an interest in analyzing the validating conditions of a covenant. In this regard, he distinguished two types of invalid covenant: those that are initially invalid from the time when they are made, and those that became invalid after a period of time. Regarding the former type, any covenant that violates the law, requires an agent to perform something that is impossible for him, takes away his right of self-defense in an emergency, or is performed without knowing to whom it is performed is initially invalid. For the other type, an already concluded covenant may become invalid after a period of time. This includes the cases in which the obligations to the covenant have been fulfilled or waived, in which circumstances change and the conditions of the initially valid covenant are no longer satisfied, or in which one party to the covenant has reasonable doubts about the other party’s willingness to perform.31 Readers who are familiar with Hobbes know that the fundamental reason why the state of nature is an existential paradox lies in the fulfillment dilemma. According to Warrender, this is not because natural law is not law or that there are no moral obligations in the state of nature, but because the state of nature is a generally insecure one. Therefore, one party to the covenant generally has reasonable doubts about the performance of the other party. As mentioned above, it is precisely because of such doubts that even a covenant that has been established would become invalid. This shows that, in Warrender’s view, it is the reasonable doubts about the other party’s willingness to perform the covenant brought about by general insecurity that make the covenant in the state of nature invalid, hence the obligation being in a state of suspension. However, the suspension of obligation does not imply that the obligation does not exist. This means that the state of nature is not a moral vacuum. The biggest distinction between political society and the state of nature is that the sovereign in political society can maintain basic domestic and foreign order, that is, people in political society are generally in a secure state. For this reason, the parties to the covenant cannot invalidate the covenant due to security or reasonable doubts about the other party’s willingness to perform, as there is an authoritative and powerful sovereign-based punishment mechanism. This also shows that, the distinction between the state of nature and political society is not whether there are obligations, but whether there is an authoritative power mechanism. The sovereign does not create obligations, but creates a secure environment to ensure that obligations can be fulfilled.

In this regard, Strauss insists all along that obligations originate from contracts and are self-imposed. If converted into Warrender’s terminology, in Strauss’s view, the ground of obligation is free will. What comes from free will actually comes from consent and contract. In The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, Strauss stated that “obligation comes only on the basis of a covenant between formerly free and unbound men,”32 and “for Hobbes...the denial of a natural law, of an obligation which precedes all human contracts”;33 in the Natural Right and History, he stated: “...all obligations to others arise from contract... All material obligations arise from the agreement of the contractors, and therefore in practice from the will of the sovereign.”34 While Warrender believed that a contract or covenant is only an instrument that incurs an obligation and does not itself create the obligation. According to him, Hobbes tends to describe the obligations of citizens as merely fulfilling the terms of a covenant, but when he considers the full scope of such obligations, he turns in fact to the law of nature in a broader context.35 In other words, the reason why a covenant or contract is binding or can incur obligations is not because the breach of contract makes a formal contradiction, but because it is a requirement of natural law, and therefore obligations originate from natural law.

It can be seen from the above that, like Oakeshott, Strauss based obligation on the free will established by Hobbes, while Warrender believed that Hobbes still resided in the natural law tradition and based obligation on natural law. The fundamental difference lies in the understanding of Hobbes’s natural law. Strauss maintained that, for Hobbes, natural law was not a law in the strict sense. In The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, Strauss makes it clear that Hobbes explicitly “denies that the natural moral law is really a law.”36 For Hobbes, the denial of natural standards was irrefutably evident on the basis of his materialist metaphysics;37 in his Natural Right and History, he also states: “The moral law became, therefore, the sum of rules which have to be obeyed if there is to be peace. Just as Machiavelli reduced virtue to the political virtue of patriotism, Hobbes reduced virtue to the social virtue of peaceableness.”38 In his paper On the Basis of Hobbes’s Political Philosophy, he came to a similar conclusion that Hobbes proposed that, prior to the establishment of civil society there is no law or no natural law independent of the command of the sovereign.39 Warrender took Hobbes’s words very seriously: “These dictates of Reason, men use to call by the name of Lawes; but improperly: for they are but Conclusions, or Theoremes concerning what conduceth to the conservation and defence of themselves; whereas Law, properly is the word of him, that by right hath command over others. But yet if we consider the same Theoremes, as delivered in the word of God, that by right commandeth all things; then are they properly called Lawes.”40 So why does Warrender hold so tightly to the conception of God in the subjunctive mood in the second half of the passage? For if natural law were merely a deliberative or reflective theorem, it would be no more capable of imposing normative obligations on man than that in the robber situation.41 So if Hobbes’s theory of obligation is to be saved, Warrender must, with textual interpretation techniques, treat natural law as real law, and only real law can impose normative obligations. For Hobbes, “Law in general, is not Counsell, but Command; nor a Command of any man to any man; but only of him, whose Command is addressed to one formerly obliged to obey him.”42 Therefore, he must remove the virtual veil of God in order to construct a coherent theory of obligation. Strauss explicitly denied the role of God in Hobbes’s philosophical system. He stated that “the denial of creation and providence, is the presupposition for Hobbes’s conception of the state of nature;”43 “Hobbes’s is the first doctrine that necessarily and unmistakably points to a thoroughly ‘enlightened,’ i.e., a-religious or atheistic society as the solution of the social or political problem;”44 and that “Hobbes’s unbelief is the necessary premise of his teaching about the state of nature.”45 Without the conception of God, natural law would not be real law, and there would be no room for normative obligations, so Hobbes’s philosophy would in a sense be a pure philosophy of power, which is what Strauss insists.

III. Criticism of the Hohfeldian Interpretation of Hobbes’s Theory of Rights

As mentioned above, Warrender started an academic trend that continues to this day to make Hohfeldian interpretation of Hobbes’s theory of rights; and based on which, he launched an in-depth criticism of Strauss. In recent years, this research paradigm of Hobbesian interpretation of Hobbes’s theory of rights has been severely criticized by scholars represented by Curran. Based on Curran’s theory, the core of its criticism is that whether in the state of nature or in political society, if Hobbes’s natural rights or civil rights are merely regarded as the Hohfeldian privileges or freedoms, for one thing, it will prevent us from seeing the transference or movement between rights, and therefore lose the opportunity to see the changes in the internal mechanisms of rights during the transition from the state of nature to political society; for another, it will prevent us from seeing the direct or indirect role of the sovereign and other fellow citizens in protecting citizens’ rights. Therefore, the Hohfeldian interpretation will distort Hobbes’s theory of rights and even make it difficult to constitute a theory of rights.46 So, what does Curran’s anti-criticism mean for Warrender? Can it save Strauss’s argument?

A. On the transference of rights

For Hobbes, the key step from a precarious state of nature to a secure and peaceful political society is the issue of renunciation and authorization. In the former case, it is Hobbes’s famous second law of nature: “That a man be willing, when others are so too, as farre-forth, as for Peace, and defence of himselfe he shall think it necessary,to lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himselfe.”47 So what effect on right does such renunciation (or redoundeth) have? Hobbes makes it clear: “To Lay Downe a mans Right to any thing, is to Devest himselfe of the Liberty, of hindring another of the benefit of his own Right to the same. For he that renounceth, or passeth away his Right, giveth not to any other man a Right which he had not before; because there is nothing to which every man had not Right by Nature: but onely standeth out of his way, that he may enjoy his own originall Right, without hindrance from him; not without hindrance from another. So that the effect which redoundeth to one man, by another mans defect of Right, is but so much diminution of impediments to the use of his own Right originall.”48 It seems that for Hobbes, the renunciation or transference of natural rights will not change the basic pattern of the right-obligation relation between the parties, but only the convenience of exercising the original freedom. It is on this theory that Warrender asserts that “the individual who resigns or transfers a right, takes upon himself a duty which he did not have before, but the rights of other people remain the same, whether the transference of the right in question was to them or not. Thus if, for example, the individual transfers a right to person ‘p’, but not to person ‘q’, he will have a duty not to hinder ‘p’ in some respect and no duty to ‘q’ in this respect; but the rights of both ‘p’ and ‘q’ will remain the same as before.”49 Given the limitations of the times, it is understandable that Hobbes did not interpret the changes in the right-obligation relation between the parties caused by the renunciation or transfer of natural rights; however, Warrender, who has been influenced by 20th century analytic philosophy, particularly Hohfeld’s analysis of jurisprudence, really should be able to see such golden touch in right. Because, as for the effect of right produced between the involved parties due to the transference of natural right or the Hohfeldian liberty, Hobbes explicitly states “because there is nothing to which every man had not Right by Nature: but onely standeth out of his way, that he may enjoy his own originall Right, without hindrance from him.” This actually means that an obligation has been created on the transferor; and in contrast, for the other party P, it has correspondingly added a claim right against the transferor, namely “without hindrance from him”.

If we apply such relations to Hohfeld’s system of legal concepts, in this context, the transfer of a privilege will create a new obligation on the transferor; and at the same time, the other party will have a new right or his original privilege will become a real right — a claim right or what Warrender calls an entitlement. From this point of view, the legal relations between the parties will be completely changed. Perhaps Warrender attaches too much importance to a clear distinction between Hohfeld’s four forms of ascription of rights (right, privilege, power, and immunity), which prevents him from seeing the transference between rights and leads him toward a certain metaphysical view of rights. So in this sense, Curran’s criticism is rational.50 Because of this, his criticism of Strauss that no obligation can be derived from natural rights (i.e. privilege) is untenable; but this does not mean that Strauss correctly grasped the legal principles involved. As mentioned above, Strauss believes that obligations originate from static contracts, rather than from the dynamic conversion from privileges to claim rights. Of course, the problem with the conceptual analysis lies with Warrender rather than Hohfeld, because Hohfeld does not deny the transference of rights. It’s just that he died young and didn’t fully develop his theory in this regard. So from this perspective, Curran’s understanding of Hohfeld might be one-sided and superficial.51 Complicating the matter, however, is the fact that the state of nature lacks what Warrender calls sufficiently safe conditions for the validity of laws. So Hobbes stated: “The force therefore of the law of nature, is not in foro externo, till there be security for men to obey it, but is always in foro interno, wherein the action of obedience being unsafe, the will and readiness to perform is taken for the performance.”52 This means that an action of obligation formed by the second law of nature is in a state of suspension, and since the inner or conscience realm is always safe, the person on the other part always has natural law obligations in conscience. From this point of view, in addition to the possible conversion of legal relations at the same level of action, there is the definite conversion of legal relations at the level of conscience and morality that are different from the action. Such dual legal relations and the conversion principle may not be accommodated by Hohfeld’s theory of legal relations. This three-dimensional theory of the relationship between rights and obligations may have wider applicability and more explanatory power for legal and moral phenomena in life. For example, regarding the so-called “natural claims” beyond the statutes of limitations, it is difficult to explain using only this flat conceptual system. At this time, the fundamental reason why the debtor has no right to request a return after the creditor is paid may not lie in the relationship between rights and enforceability,53 but in the fact that the debtor still has the moral obligation to repay. Therefore, in this case, a three-dimensional legal structure is presented because of the intertwined relationship between law and morality. This is where Hobbes or Hobbes’s theory of rights constructed through Warrender might bring to the innovation of legal and moral philosophy.

B. On the issue of civil rights

As mentioned above, Warrender argued that Hobbes’s concept of rights has two basic meanings: claim right, and privilege, with the latter being more common and important. But the rights of sovereign are standard claim rights, that is, citizens as the other party bear the related obligations. The rights of citizens are more of a freedom from obligation, namely, privilege.54 This is in terms of political or moral rights as a whole. However, for Leviathan is an artificial man, it can only be ruled with an artificial will, i.e., laws.55 In this way, the vast majority of moral or political rights will be transformed into positive legal rights, and a considerable number of civil rights will accordingly be transformed into rights in the sense of claims, and even so, such claims can be used against sovereignty. “If a Subject have a controversie with his Soveraigne, of Debt, or of right of possession of lands or goods, or concerning any service required at his hands, or concerning any penalty corporal, or pecuniary, grounded on a precedent Law; He hath the same Liberty to sue for his right, as if it were against a Subject.”56 This is very similar to modern administrative litigation, in which the rights enjoyed by citizens are not just a freedom or privilege called by Hobbes, but a claim right or real right. Similarly, in the legal context, Hobbes’s right to punish is no longer a natural right or privilege as claimed, but is converted into a claim right.

However, in the Hobbesian community, the civil rights discussed by scholars do not mainly refer to those in the positive legal sense, but to what Hobbes calls “civil liberties” and citizens’ “real freedom.”57 The mainstream opinion among Hampton and others still indicates that it is the Hohfeldian privilege. If this is the case, then Hohfeld’s theory of the relations between rights and obligations can certainly be easily applied to it, but as mentioned above, what complicates the issue is that Hobbes clearly stated that the sovereign has a natural law obligation to protect the rights of citizens. “The OFFICE of the Soveraign, (be it a Monarch, or an Assembly,) consisteth in the end, for which he was trusted with the Sovereign Power, namely the procuration of the Safety of the people; to which he is obliged by the Law of Nature, and to render an account thereof to God, the Author of that Law, and to none but him. But by Safety here, is not meant a bare Preservation, but also all other Contentments of life, which every man by lawful Industry, without danger, or hurt to the Common-wealth, shall acquire to himselfe.”58 It is precisely because Hampton and others adhere to Hohfeld’s system of conceptions that they cannot see the misplaced protection of such rights, but insist on its privilege-based nature. But because Warrender insists on Hobbes’ system belonging to natural law tradition, he can see the possible changes in rights in the political or natural sense due to the sovereign’s protection of natural law obligations. In this way, the relations between rights and obligations are no longer between two parties on the same level, because it is clear that natural law obligations are to God rather than citizens, and citizens are just beneficiaries of such protection.59 As we see now, in such a hierarchical structure of rights and obligations, it is not like the Hohfeldian legal relations that are only applicable to two parties, because there are three parties involved — citizens, the sovereign and God; besides, this structure of legal relations is no longer flat but three-dimensional. One is political and natural, and the other is moral and divine. Therefore, if Curran’s criticism applies to Hampton and others, it does not apply to Warrender, because Warrender just uses but does not copy Hohfeld’s theory. And more importantly, from Hobbes’s perspective, he transformed this flat legal relationship between two parties into a three-dimensional legal relationship of three parties, thus making the theoretical model more explanatory.

This shows that, Curran’s criticism of the Hohfeldian interpretation of Hobbes’s theory of rights has its merits. However, for that there are some intellectual flaws in his understanding of Hohfeld’s analysis of jurisprudence, and his criticism is mainly applicable to the Hobbesian studies in the field of social science by scholars such as Gauthier, Kavka and Hampton, but not applicable to Warrender’s research, its theoretical significance is destined to have limitations. In addition, because Warrender believes that Hobbes’s system belongs to the natural law tradition, in the analysis of legal rights relations, he can see the three-dimensional structure of legal relations among three parties that Curran cannot see. This may also constitute an important innovation in legal philosophy.

IV. Conclusion

In the Hobbesian research community, Warrender is often referred to together with Taylor, particularly, the Taylor-Warrender thesis, even though this is valid only in the sense of the general outline of the obligation theories. If based on the historical background, Taylor’s theory of obligation is of greater political intent than academic intent,60 then Warrender’s theory of obligation has the unique pertinence of academic thought, particularly, pertinent to Strauss’s theory of rights. Contemporary scholars generally accept Strauss’s important assertion that Hobbes is the founder of modern political philosophy. Strauss’s awareness of question is the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns, and the core focus is the legal right theory on the conversion from obligations to rights. As a scholar deeply influenced by the Oxford school of ordinary language philosophy and analytical positivist jurisprudence, Warrender draws on Hohfeld’s perspective to analyze the privilege-based nature of Hobbes’s concept of rights. For Hohfeld, privilege is the opposite of duty and is the correlative of no-right. If this is the case, then for Warrender, Strauss’s argument does not hold up, because Strauss mistakes privilege for substantive claim or moral entitlement. Obligations cannot in any way be constructed on the basis of privilege (i.e., no-duty). However, Warrender’s argument does not hold up, because he places too much emphasis on the static oppositions in Hohfeld’s system of conceptions and ignores the dynamic conversion among the conceptions. The renunciation or transference of natural rights or privileges of a natural person can make him assume a new obligation. At this point, the transferee’s privileges are also transformed into rights or claims in the true sense. In Warrender’s analysis of legal rights, what is more theoretically significant is that, on the basis of constructing Hobbes’s theory of obligation, Warrender transformed Hohfeld’s flat legal relation between two parties into a three-dimensional hierarchical structure involving three parties that is of greater explanatory power. This constitutes a possible innovation in legal philosophy in the 20th century.

(Translated by JIANG Yu)

* TANG Xueliang ( 唐学亮 ), Doctor of Philosophy, Associate Professor at the Xi’an Jiaotong University School of Law. This paper is a phased project of two general projects: the Translation and Study of Hobbes’s Of Man (Project No. 22YJA720009), a project of the Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund by the Ministry of Education; and the Research on Early Modern Western Sovereignty Theory (Project No. SK2022010), a project of the Basic Scientific Research of the Institutions of Higher-learning affiliated to Central Departments.

1. Wesley Hohfeld. Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning, translated by Zhang Shuyou (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2022), 54.

2. Wang Yong, An Analysis and Reconstruction of Private Right: Analytic Jurisprudence as a Methodological Basis for Civil Law (Beijing: Peking University Press, 2020), 102.

3. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 79.

4. Ibid.

5. Wesley Hohfeld, Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning, translated by Zhang Shuyou (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2022), 69.

6. Ibid., 61.

7. Ibid., 65.

8. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 18-20.

9. David P. Gauthier, The Logic of Leviathan: The Moral and Political Theory of Thomas Hobbes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), 30.

10. Gregory S. Kavka, Hobbesian Moral and Political Theory (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 315.

11. Jean Hampton, Hobbes and the Social Contract Tradition (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 51.

12. Perez Zagorin, Hobbes and the Law of Nature (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009), 29.

13. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 3.

14. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 22.

15. Howard Warrender, “Obligations and Rights in Hobbes,” 37 Philosophy 142 (1962): 355-356.

16. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 120.

17. Leo Strauss, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, translated by Shen Tong (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2001), 2.

18. Ibid.

19. George Croom Robertson. Hobbes (London: Forgotten Books, 2015), 57.

20. Ibid., 155.

21. Michael Oakeshott, Hobbes on Civil Association (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1975), 17.

22. Yves Charles Zarka, La Decision Metaphysique De Hobbes: Conditions De La Politique, translated by Dong Hao, et al. (Beijing : SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2020).

23. Leo Strauss, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, translated by Shen Tong (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2001), 186-187.

24. Howard Warrender, “Obligations and Rights in Hobbes,” 37 Philosophy 142 (1962): 355.

25. Eleanor Curran, Reclaiming the Rights of the Hobbesian Subject (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 101.

26. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 21.

27. Ibid., 275.

28. Ibid., 277.

29. Ibid., 99-102.

30. Ibid., 26.

31. Ibid., 35-51.

32. Leo Strauss, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, translated by Shen Tong (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2001), 28.

33. Ibid., 66.

34. Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History, translated by Peng Gang (Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2006), 191.

35. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 249.

36. Leo Strauss, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, translated by Shen Tong (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2001), 66.

37. Ibid., 199.

38. Ibid., 191.

39. Ibid., 166.

40. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 100.

41. L. A. Hart, The Concept of Law, translated by Xu Jiaxin and Li Guanyi (Beijing: Law Press · China, 2011), 75-83.

42. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 173.

43. Leo Strauss, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: Its Basis and Its Genesis, translated by Shen Tong (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2001), 147.

44. Ibid., 203.

45. Ibid., 181.

46. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 153-176.

47. Ibid., 80.

48. Ibid., 81.

49. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 54.

50. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 97-100.

51. Arthur Yates, “A Hohfldian Analysis of Hobbesian Rights,” 32 Law and Philosophy 4 (2013): 417-422.

52. Thomas Hobbes, De Corpore Politico (London: John Bohn, 1839), 108.

53. Wang Yong, An Analysis and Reconstruction of Private Right: Analytic Jurisprudence as a Methodological Basis for Civil Law (Beijing: Peking University Press, 2020), 199.

54. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 199-200.

55. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 3.

56. Ibid., 143-144.

57. Tang Xueliang. “The Political Philosophical Foundation of Hobbes’s Thought of the Rule of Law,” Journal of the History of Political Thought 2 (2022).

58. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1994), 219.

59. Howard Warrender, The Political Philosophy of Hobbes: His Theory of Obligation, translated by Tang Xueliang (Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2022), 192.

60. Charles D. Tarlton, “Rehabilitating Hobbes: Obligation, Anti-Fascism and the Myth of A‘Taylor Thesis’,” 19 History of Political Thought 3 (1998): 407-438.