Digital Development Rights in Developing Countries:Where the Governance Rules for Cross-Border Data Flows

LI Yanhua*

Abstract: The digital development rights in developing countries are based on establishing a new international economic order and ensuring equal participation in the digital globalization process toachieve people’s well-rounded development in the digital society. Therelationship between cross-border data flows and the realization ofdigital development rights in developing countries is quite complex.Currently, developing countries seek to safeguard their existing digitalinterests through unilateral regulation to protect data sovereignty andmultilateral regulation for cross-border data cooperation. However,developing countries still have to face internal conflicts between national digital development rights and individual and corporate digital development rights during the process of realizing digital development rights. They also encounter external contradictions such as developed countries interfering with developing countries’ data sovereignty, developed countries squeezing the policy space of developing countriesthrough dominant rules, and developing countries having conflicts between domestic and international rules. This article argues that balancing openness and security on digital trade platforms is the optimalsolution for developing countries to realize their digital development rights. The establishment of WTO digital trade rules should inherently reflect the fundamental demands of developing countries in cross-border data flows. At the same time, given China’s dual role as a digital powerhouse and a developing country, it should actively promote the realization of digital development rights in developing countries.

Keywords: developing countries · digital development rights · cross-border data flows · governance rules

The arrival of Industry 4.0 reflects the profound impact of data on all economic sectors. Cross-border data flows have further sped up this trend. The actual development status of various countries shows that the data divide is deepening the traditional digital divide related to connectivity, reflecting significant differences in digital capabilities between and within countries.1 In terms of international rulemaking, the U.S.template upholding the concept of freedom that advocates for the “maximum possible free flow of cross-border data” and the European template that “prohibits datalocalization and advocates for cross-border data flow with restrictions in the contextof human rights protection” have been widely adopted in bilateral and multilater alagreements. Developed countries in Europe and North America are better at promoting international digital rules in favor of their economic interests when negotiating with developing countries, a reality that has affected the national industrial interests of developing countries to some extent. As a result, developing countries are losing their bargaining power in international data governance rules. For example, only Brazil and Chinese Taipei are developing countries (regions) among the 12 members who submitted the proposal for the cross-border data flows section of the consolidated text of the December 2020 WTO e-commerce negotiations. China, a digital powerhouse,is also a developing country. Now China needs to consider how to reflect the commoninterests of developing countries, including itself, in advancing the formulation of therules on cross-border data flows in the WTO e-commerce negotiations for developing countries to realize their digital development rights.

I. Review of Digital Development Rights in Developing Countries Concerning Cross-border Data Flows

A. Conceptual analysis of digital development rights in developing countries

The Declaration on the Right to Development, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in its resolution 41/128 on December 4, 1986, recognizes that“the right to development is an inalienable human right” and development is “acomprehensive economic, social, cultural and political process every human personand all peoples are entitled to”. In the wave of globalization with states as the mainplayers, the right to development of “every human person and all peoples” is subject to the realization of the right to development of each state. The right to developmentis, therefore, not only an individual right but also a collective right. With the rapid development of the digital economy, the right to digital development has gradually taken shape in recent years. As for the concept of the right to digital development, the paper argues that it is not a reshaping of the concept of the right to development, but a theoretical update of the right to development in the digital age, which re-emphasizes the importance of realizing the right to development in the digital sector given that data have been widely used in all political, economic, cultural and social aspects. The paper holds that both individuals and collectives are the subjects of the right to digital development, and particular attention needs to be paid to the rights of vulnerable collectives, i.e., developing countries. Individuals, corporations, and states are all subjects of obligations concerning the right to digital development. States and corporations should fully respect the right to development of the data subjects to promote and protect human rights. At the same time, each state should respect the permanent data sovereignty of other states. In particular, developed countries should fully respectthe rights of developing countries to promote the establishment of a new international economic order.2 Furthermore, each state, as the subject of rights and obligations,should abide by the principles of international law on cooperation. The right to digital development encompasses not only the right to develop digital citizenship, that is, theright to data equality and data self-determination for equal participation in digital activities, but also the right to develop the digital economy, that is, the ability to access the resources of the digital economy. For developing countries, it especially means the right to receive technical assistance from developed countries in digital capacity-building and bridging the digital divide. Furthermore, globalization has laid a solid foundation for developing countries to realize their right to development. However, their development is largely restricted by the resource allocation of developed countries due to their less competitive position. In this context, developing countries should adopt development strategies based on their development situations to promote the further realization of the right to development. This leads to the theme of this paper — “the digital development rights in developing countries” in the context of globalization. In brief, digital development rights in developing countries are based on establishing a new international economic order and ensuring equal participation in the digital globalization process to achieve people’s well-rounded development in the digital society and the ultimate transformation and upgrading of the political, economic, social and cultural development of developing countries in the digital sector.3

B. The relationship between cross-border data flows and digital development rights in developing countries

The relationship between cross-border data flows and digital development rights in developing countries is quite complex. To demonstrate the importance of cross-border data flows, the United Nations revised Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 2016. It encourages the promotion, protection, and enjoyment of human rights through the Internet and recognizes the global and open nature of the Internet as an enabler for accelerating all types of development, including the achievement of sustainable development goals. It affirms the importance of adopting a comprehensive human rights-based approach to the provision and expansion of Internet accessand invites all states to work toward bridging the digital divide in its many forms.4 In this context, the right to digital development has become an important aspect of theright to development of individuals and states, as well as an important goal in designing the mechanisms for cross-border data flows. To realize the right to digital development, it should not only facilitate the access rights of data subjects to enable a freer flow of data based on data security but also pay special attention to the economic demands of developing countries. Developing countries as a whole have long recognized the importance of cross-border data flows, as reflected in the “Declaration”(A/36/573)adopted by the Foreign Ministers of the Group of 77 on September 29, 1981, in which they expressed support for the United Nations Development Programme to developthe information network.5 Data as an economic resource plays an increasingly important role in cross-border data flows. Despite the growth of the digital economy indeveloping countries in recent years, the traditional “digital divide” between developed and developing countries remains deep from the perspective of Internet connectivity, access, and use.6 The UNCTAD’s Digital Economy Report 2021 — Cross-border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow points out that the reason is that only 19% of the population in developing countries uses the Internet compared to 87% in developed economies.7 And developing countries cannot turn data into digital intelligence. Therefore, on the one hand, most developing countries are in a subordinate position in the global digital economy, and some of them can only be raw data providers for global digital platforms;8 On the other hand, countries in Europe and North America maintain their advantageous position in international competition by implementing European and U.S. cross-border data flow regulations. As a result, most developing countries can only be recipients of global digital governance rules and are suffering from the negative impact of “digital colonialism”9. The least developed countries with poor digital infrastructure, weak digital capabilities, and limited regulatory capacity are subject to significant challenges. For this reason, some developingcountries have begun to oppose the establishment of cross-border data free flow agreements at the international level. One important reason is that if a country participates in cross-border data transfer systems before its domestic data ecosystem is firmly established, its data assets may be divested by foreign entities, and intellectual property rights and key data resources will be owned by companies of developed countries.The majority of developing countries will not be able to benefit from the global digital value chain. In addition to the economic dimension, data often concern the protection of individual privacy and human rights, as well as important national security interests and national sovereignty. Therefore, some developing countries claim that data restriction measures are necessary for developing their domestic digital sectors and protecting their economic and social interests, including data localization, content filtering measures, and continuing to impose tariffs on electronic transmissions.10 However, it should be admitted that access to data is rather a necessary than sufficient condition for development. For countries with weaker industrial capacity, refusing cross-border data flows will exclude them from the world network system, which will to some extent reduce their economic development opportunities and their citizens’ welfare.

This paper holds that developing countries are currently facing the dilemma of the squeezed development space of the domestic digital industry and the weakened negotiating power of international digital rules. Therefore, to realize the digital development rights in developing countries and ultimately build an international data rule governance system in the context of cross-border data flows, how to balance the interests of various stakeholders and address concerns about the participation of developing countries in international rule-making has become one of the key issues to besolved urgently. In this context, this paper intends to evaluate and further analyze thecurrent situation of cross-border data flow governance from the perspective of developing countries to break the shackles of studying cross-border data rules formulated by developed countries in Europe and North America.11 It also has great significance for the economic and trade agreement negotiations between China and other developing countries, as well as between developing and developed countries. This will be addressed in the final part of this paper.

II. The Dual Approaches to the Realization of Digital Development Rights in Developing Countries

As mentioned above, the realization of digital development rights as specified in international law includes both respect for sovereignty and international cooperation. Therefore, the approaches to the realization of digital development rights in developing countries are to defend data sovereignty through regulatory measures internally and seek international cooperation in cross-border data flows externally. Developing countries have adopted different regulatory approaches based on their different roles in governing the digital sector. The following section will elaborate on the setting of specific rules under different regulatory approaches in developing countries, and summarize the overall trends reflected by these specific rules.

A. Developing countries defend their data sovereignty through unilateral regulation

Data sovereignty is the extension and expression of national sovereignty in the field of data in the digital economy era. Data sovereignty means that a state has full control over the data stored and processed and independently determines who has access to such data. Claims to data sovereignty stem from the emphasis on national autonomy and national infrastructure security, with the most important practice being data localization; Claims to data sovereignty also stem from states competing for economic autonomy, which is mainly reflected in the national economy’s independence of foreign technologies and service providers; Furthermore, claims to data sovereignty can also stem from the realization of user autonomy and individual self-determination.12 The international game of data legislation is a competition between states for data sovereignty, behind which lies the real interests of these states. Russia and China place greater emphasis on maintaining national security and public safety; India is more focused on the development of its domestic digital economy; Latin American countries, influenced by the European Union, emphasize the importance of the right to privacy and data protection; and African and Southeast Asian countries encompass all diverse interests mentioned above.

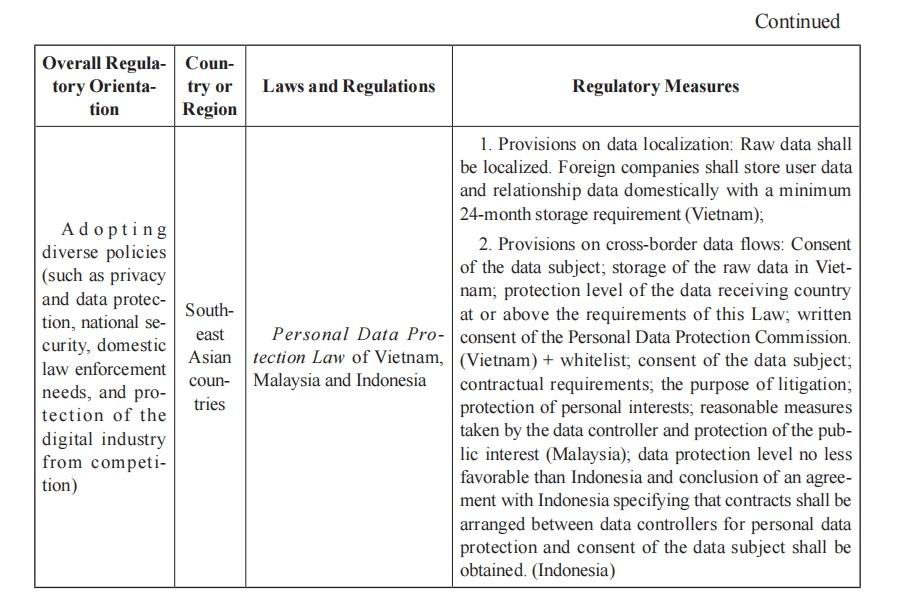

From the perspective of legislation regulating cross-border data flows, countries mainly maintain their data sovereignty through provisions on data localization and provisions on outbound data transfer (as shown in Table 1). Data localization is a widely used legal tool in most developing countries. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development defines data localization as a mandatory legal or administrative requirement directly or indirectly stipulating that data be stored or processed, exclusively or non-exclusively, within a specified jurisdiction.13 Data localization can be classified into de jure and de facto data localization. Compared to the EU’sefforts to increase restrictions on cross-border data transfers and thus form the world’s largest de facto data localization framework, data localization in developing countriesis more about strengthening control over data through direct provisions for data localization. Recent trade agreements have translated key elements of data localization into restrictive market access requirements that do not require the use or establishment of computing facilities as a precondition for conducting business. It can be seen from the analysis of data localization provisions in Table 1 that, the degree of local storage of data mainly depends on the type of data: in Russia, Brazil, and Vietnam, all personal data of citizens; in China, personal data contained in the critical information infrastructure and data processed by personal information processors up to a specified amount; in South Africa, data contained in the critical information infrastructure and natural resources data; in Kenya and Nigeria, sensitive data; in India, “sensitive personal data” and key person data; in Chile, “important” or “strategic” outsourced data;in Sener, government data; or rather than depending on the type of data, preferential treatment is given to domestic storage of data or otherwise, so as to achieve the same effect of data localization, such as in Peru, Ghana, and Seychelles; or making use of domestic infrastructure an access requirement, such as in Venezuela. However, with the development of geopolitics of data localization, large tech companies in the Westand those in India and China are competing with each other, while Indonesia and Vietnam have bowed to pressure and loosened certain regulations on data localization.14 With the development of digital globalization, most developing countries have provisions for outbound data transfer in their data laws, though the least developed countries (such as Libya, Namibia, and Congo) have not yet implemented any cross-borderdata flow regulations. Following the example of the EU, some countries have adopted tools such as adequacy protection lists, data subject consent, legitimate purposes,standard contract terms, binding corporate rules, institutional certification, national institutional approvals and security assessments, and binding international agreements.Developing countries can combine the above tools in various ways to safeguard their respective key interests. There are very few restrictive measures for data inflow, for example, China only blocks information that is prohibited by laws and regulations from being published or transmitted through cross-border data security gateways.15 On the contrary, a few developing countries, such as Ghana, have even ceded data sovereignty by governing foreign citizen data processing with foreign data protection laws.16

.png)

.png)

B. Developing countries cooperate on cross-border data flows through international trade agreements

Firstly, in terms of bilateral agreements, there are generally three types of data flow clauses according to the binding degree of cooperation: non-binding, binding,and intermediate clauses. Non-binding clauses have no legal effect on both parties who only consider cross-border data flows as part of their cooperative activities.19 For example, the 2017 Argentina-Chile Free Trade Agreement is one of the few to mention only that both parties “recognize” the importance of prohibiting data localization.Binding clauses have a legal effect on both parties who commit to the cross-border flow of data.20 Intermediate clauses infer that both parties agree to take into consideration commitments related to cross-border data flows in future negotiations.21 In terms of the trade agreements regulating cross-border data flows through bilateral cooperation involving Latin American countries, 62 preferential trade agreements are related to e-commerce and data flow, of which 29 agreements were concluded with developed countries and 33 with developing countries.22 India has also concluded digital trade clauses in free trade agreements with other countries, such as the emphasis on mandatory localization in the UAE-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement and the prohibition of data localization in the India-EU Free Trade Agreement negotiations. For African countries, only the EU-Tunisia Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (Draft) addresses data protection and prohibition of data localizationin cross-border data flows. In contrast, the bilateral free trade agreement between China and Russia contains no provisions on cross-border data flows.

Secondly, In terms of regional agreements, cross-border data flow clauses involved are mostly binding and have the following characteristics: (1) The cooperationdegree varies a lot in different regional agreements concluded by developing countries.For example, ASEAN countries have the highest degree of cooperation on cross-border data flows. The ASEAN Framework on Personal Data Protection, ASEAN Data Management Framework, ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses for Cross Border Data Flows (MCCs), and ASEAN Cross Border Data Flows Certification Mechanism comprehensively regulate cross-border data flows within ASEAN countries. Latin America comes next. The Additional Protocol to the Pacific Alliance Framework Agreement signed by Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru does provide a prototype for provisionson cross-border data flows and data localization.23 A signatory state to the Conventionfor the Protection of Individuals concerning Automatic Processing of Personal Data,Russia has signed the amended Protocol to ensure the free flow of data to and from European countries. However, due to geopolitics, Russia’s cooperation with other European countries on cross-border data flows is limited.24 Africa has the lowest cooperation degree on cross-border data flows. Only 5 countries have ratified the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection, and cross-border data flow has not yet been included in the development agenda. (2) The rules of international law governing cross-border data flows are fragmented, with different developing countries joining different or no agreements. For example, Brunei, Malaysia,and Vietnam are all members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). To protect its cyber frontier from infringement by other advanced digital economies and avoid conflict with its policy priorities of data localization,India has shown great reluctance in negotiations concerning digital affairs such as the framework of the Osaka Declaration on the Digital Economy and the RCEP. (3)Most digital agreements regulating cross-border data flows are currently led by developed countries, such as the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DE-PA,)25 the Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR), the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement(USMCA), and the CPTPP.

Thirdly, In terms of multilateral agreements, developing countries are generally negative about WTO plurilateral negotiations. Due to different national stances, Singapore advocates for freer data flow highly in line with the U.S. India has reservations about the plurilateral approach and emphasizes the importance of policy space in cloud computing, data storage, and data flow. Cambodia and Vietnam are not part of the WTO plurilateral negotiations. Some African countries have opted into the WTO plurilateral negotiations on e-commerce, but have not proposed provisions on cross-border data flows. Important members such as South Africa remain outside the negotiations.26 China has emphasized the rules of traditional cross-border e-commerce and the rights and interests of developing countries but has not proposed any provisions on this part, considering the difficulty of reconciling its data security concerns with most developed countries’ stance on free data flow. Russia has divided e-commerce issues into those to be further clarified in WTO agreements and those not yet covered such as personal data protection and “secure data flows”, although it has not further elaborated on what constitutes “secure data flows”.27 It is worth noting that Brazil follows the provisions of the CPTPP, with the same substance as the U.S. and Canadian proposals, but recognizes the regulatory requirements of members in terms of data flow, and lists in detail the “legitimate public policy objectives” in the text of the WTO’s e-commerce chapter28, although the legitimacy of some objectives remains to be discussed.

In summary, international digital trade rules are organized under “isolated” and “overlapping” fragmentation, which will affect the bridging of the digital divide and the stability of the international digital trade governance system.29 Under “isolated”fragmentation, some developing countries have been influenced by the “Brussels effect” of the EU and adopted regulations similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).30 By learning from the rules, most developing countries have also safeguarded their security by embedding data localization clauses to control data. Under “overlapping” fragmentation, various trade agreements, including CBPR, USMCA, CPTPP, RCEP, and DEPA, have overlapping paradigms on cross-border data flow provisions, leading to a complicated spaghetti bowl phenomenon.31 In the courseof negotiations under the WTO framework, developing countries have rarely raised the issue of cross-border data flows or emphasized the need to retain certain policy autonomy in this area.32 In this context, developing countries will undoubtedly faceinternal and external difficulties in the process of realizing the right to digital development.

III. Internal and External Difficulties in the Realization of Digital Development Rights in Developing Countries

A. Internal conflicts between national digital development rights and individual and corporate digital development rights

The benefits of the realization of national digital development rights are not always consistent with those of the realization of individual and corporate digital development rights. For developing countries, the way to maximize the benefits in the short term is to utilize digital resources and strengthen digital infrastructure capacity building, while at the same time achieving the effect of safeguarding data security and national security. Data localization provisions have undoubtedly served as one of the legal tools for developing countries to achieve these goals. In the past 4 years,the number of data localization measures implemented around the world has doubled.Compared with 35 countries implementing 67 barrier measures in 2017, 62 countries around the world have implemented 144 restrictive measures today. Furthermore,another 38 data localization policies have also been proposed or drafted in additional countries.33 Developed countries regard restrictions on cross-border data flows and localization requirements as major digital trade barriers while developing economies enforce such measures by advocating “digital nationalism”.34 Some scholars argue that data localization is the data defensiveness of the state to pursue the goal of “satisfaction” rather than “optimization” in its policies on cross-border data flows.35 Thequestion is whether data localization can truly realize digital development rights indeveloping countries. If data are stored domestically, the government will have to work on the operation and efficiency of the system operators and incur double operational costs. Consumers may have to bear additional costs, which will curb early development in developing countries. Data localization will lead to excessive government control and monitoring of citizens’ data, leading to public power interference in the private rights of data subjects. For example, in June 2022, the Indian government required VPN providers to provide customer data, otherwise subject to one-year imprisonment, which in fact could lead to a violation of customer privacy and increase the risk of data breach. Pakistan has allowed the telecommunication authority to intervene on behalf of law enforcement agencies to demand user data from social mediacompanies by circumventing existing data access and privacy protection measures.36Most developing countries lack adequate infrastructure to collect and manage data,making it difficult to protect data security and thus weakening data subjects’ right todigital development. Even if some developing countries establish reliable infrastructure to store data, they may not have sufficient incentives in their market environment to attract leading cloud service providers. Therefore, data localization will preventcloud service providers from best practices for cybersecurity. Since the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict, considering the serious threat to national data security dueto the war, Ukraine has been discussing or already moved abroad about 150 registered databases or backup copies of important data from different government departments and offices.37 Data localization will put companies, especially start-ups, under tremendous financial pressure and affect their technological innovations. Data localization will also prevent data subjects from enjoying high-quality digital services and achieving full development. According to the report,38 developing countries have low capacity indicators to create a data-driven economy and seem unable to manage data well.Instead, they need to look externally for robust cloud computing solutions to manage and protect data to benefit from a data-driven economy. For example, Microsoft and Amazon have opened their first African data centers in South Africa.39 However, as acounter-example, based on India’s huge market potential, its fintech companies support data localization to ensure a fair environment for the competition between India’s startup ecosystem and global tech giants.

In terms of cross-border data flow provisions, the whitelisting and prior approval mechanisms of some developing countries seem to pose potential limitations on the consent mechanism of data subjects, i.e., the former is a precondition rather than an optional condition for the latter. This is different from the understanding of the consent mechanism in developed countries such as Japan. This means that if the data inflow country does not meet the conditions, the data cannot be transferred to that country even if the data subject has given consent, thus making it difficult for the data subject to enjoy convenient digital services. The cumbersome prior approval mechanism also adds to the filing burden of digital companies and causes a short-term impact on their digital economic performance. In addition, as an IT and IT service export center, India’s restrictions on the cross-border transfer of sensitive personal data such as medical and financial data, may affect the demand for Indian IT services from other countries. When the restrictive nature of data flow provisions moves very close to the strictest level, it could lead to the effect of data localization, resulting in the improper interference of the state in individual and corporate digital development rights.

B. External contradictions in the realization of national digital development rights

1. The long-arm jurisdiction of developed countries constitutes interference in the digital sovereignty of developing countries

A state’s sovereign decisions on Internet affairs, whether voluntary or not, will have a direct or indirect impact on other territories, thus violating the principle of non-interference in sovereignty to a certain extent.40 Developed countries are seeking to expand this impact. In terms of the allocation of interests in data sovereignty, in addition to attracting data and digital infrastructure back to its traditional jurisdiction, the EU also understands data sovereignty to include the ability to protect personal data,thereby enhancing its international influence, including indirect control over enterprises in data inflow countries as well. The U.S. has spared no effort in promoting the free flow of data backed by its powerful digital enterprises. The U.S. restrictions on TikTok and Huawei are seen as a major step in its fight for data sovereignty.41 At the sametime, it has adopted a minimum level of contact to exercise long-arm jurisdiction overcross-border data flows, and, through the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act(CLOUD), enabled law enforcement agencies to have access to data owned, stored, and controlled by U.S. companies, regardless of whether the data is stored within oroutside the U.S. It can be drawn that Europe and the U.S. have pursued their data sovereignty strategies and realized their power distribution over large digital companies through different ways of extraterritorial jurisdictions. Unlike Europe and the U.S.,which are actively expanding digital sovereignty, developing countries tend to maintain digital infrastructure and data resources in the traditional sense of sovereignty. On top of this, they also actively respect the data sovereignty of other countries. The result of these two different regulatory approaches is that developed countries, through the exercise of their legislative power, have transcended the sovereignty of other countries and expanded their digital interests. In short, developed countries seek to solidify their established “data advantages” by excluding the sovereign jurisdiction of other countries within their territories, thereby depriving emerging developing countries of their digital development rights in related areas.42

2. Developing countries are either rule recipients or rule excluders in rulemaking cooperation on cross-border data flows

Both developed and developing countries have participated to varying degrees in preferential trade agreements containing e-commerce provisions, with 49% negotiated and concluded between developed and developing countries and 47% between developing countries.43Bilateral,regional,and multilateral agreements are mostly extensions of the U.S. and European templates. From a historical perspective, traditional developed countries,taking advantage of their rich experience in international economic and trade rule-making, have been better at promoting international digital trade rules in favor of the economic interests of developed members in the course of negotiations with developing countries. From the perspective of cross-border data flow provisions,the U.S. template has focused too much on the open end of cross-border data flows and thus ignored developing countries’ goal of legitimacy. On April 21, 2022,the U.S. issued the Global Cross-border Privacy Rules Declaration 44 based on the CBPRs system, transforming it into a system that all countries or economies can join to enable the flow of global data to U.S. companies through relaxed cross-border privacy standards. The U.S. template was first followed by the CPTPP,45 which stipulates in Article 14.11 that members may formulate their regulatory requirements for the cross-border transfer of personal data except for a “legitimate public policy objective”,provided that it does not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade. Due to the ambiguous definition, the “respective regulatory requirements” are not as binding and enforceable as they should be. The USMCA just removed the exception provisions46 for “regulatory requirements”, showing an increasingly obvious sign of “prioritizing cross-border data flows”. The European template, due to its overemphasis on strict protection of personal data privacy,has overlooked developing countries’ demand for realizing their digital economic development rights. The 2018 EU Model Contract Clauses only prohibit specific restrictions on data flow rather than restrictions on personal data transfer under the GDPR,which includes a wide range of privacy and data protection exceptions.47 At the sametime, the EU has also adopted the adequacy decision-making mechanism as a tool fortrade negotiations. Generally speaking, developing countries have to accept the data flow clauses in FTAs under pressure and circumstances, thus giving up opportunities for the development of local industries. For example, some overseas companies in developing countries choose to store data locally for fear of high fines. In addition, some countries, as contracting parties to many agreements, bear overlapping obligations,leading to fragmentation in the application of the rules. When Argentina and Uruguay transfer data from the EU as data inflow countries and transfer data out to a thirdcountry, it may constitute a violation of EU cross-border data rules. On the other hand,data localization has become a highly controversial issue between developed and developing countries. In recent years, led by developed countries, clauses prohibiting data localization have become parallel provisions for cross-border data flows. Almost all agreements have binding clauses on data localization in contrast to cross-borderdata flows. The 2015 Japan-Mongolia Free Trade Agreement is the first agreement with such clauses.48 Article 14.13.2 of the CPTPP makes the prohibition of data localization a rule of principle and adopts exception provisions similar to the cross-border data flow provisions.49 Although the USMCA reiterates the demand for “implementing non-compulsory localization of data storage”, and removes the contracting parties’regulation exceptions and legitimate public policy objective exceptions, the “policy space” for data industrialization in developing countries is still undoubtedly reduced.

Compared to other developing countries, China is the world’s second-largest data collector,50 and the world’s largest e-commerce market, and leads one of the three major data governance models. Compared to Europe and the U.S., China emphasizes more on the crucial role of the government in data governance, and its concept of data sovereignty is more related to data security and national security. This is reflected in the RCEP, which expands CPTPP exceptions to a certain extent. First, it increases the flexibility of national regulatory power of contracting parties in their discretion “asthey deem necessary”; second, it adds specific national security exceptions through provisions on cross-border data flows and location of computing facilities, namely the“essential security interests” clause, which is restricted by necessary measures, but not subject to challenge by other parties.51 However, such a clause is sometimes disguised as a tool for national commercial protection, which may seriously affect the free flow of data. Out of the concern about data outflow to China, the U.S. and Europe have restricted the flow of data to China through investment screening mechanisms and other measures to curb the risk of extensive data monitoring in China.52 At the sametime, China is excluded from the new global CBPR, and the OECD Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities also indirectly precludes China from entering into agreements with Europe, the U.S., and Japan concerning government access to data.53 In particular, China faces increased pressure from the U.S. when it engages in regional cooperation.54 As China is excluded from various rules, large Chinese tech companies have to establish local data centers in Europe and the U.S. or arrange local cloud storage for data sourced there, thus increasing their operating costs, reducing their data resource integration ability,55 and ultimately affecting their global development.

3. The realization of digital development rights in developing countries may conflict with international rules

Different countries have different measurements for the use and flow of data based on various considerations such as cybersecurity, national security, privacy protection, industry competition and taxation, law enforcement needs, and the regulatory environment in the technology sector. While the realization of digital development rights requires a dynamic balance between trade and non-trade goals, data localization measures in some developing countries are of questionable purpose and exceed the need and proportion as required, posing significant regulatory risks and failing the compliance check of WTO and other trade agreements. In this regard, WTO jurisprudence effectively demonstrates that the WTO dispute settlement mechanism can beapplied to solve trade conflicts arising from the Internet sector. The U.S.-Gamblingand Betting is a classic case to prove that the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) can be applied to services provided electronically and clarify the key concepts of service regulation, such as the defense scope of “public morality/publicorder” stipulated in GATS Article 14.56 Under the GATS, due to the discriminatory nature of data localization measures, foreign companies may be forced to bear additional operating costs or leave the market, with favorable competitive conditions skewing domestic suppliers.57 Data localization measures in developing countries may therefore violate the specific market access commitments under GATS Article 16 and the specific national treatment commitments under Article 17. Even though the general exception clause in GATS Article 14 provides possible exemptions for member states to pursue non-trade goals, industry competition and taxation, law enforcement needs,or the regulatory environment in the technology sector should not constitute any ofthe measures. In addition, it is also difficult to pass the necessity test for data localization measures to safeguard privacy and national security, and the legal contexts of different developing countries are subject to different legal comments by the Dispute Settlement Body Panel. For example, India practices economic protectionism in thedigital sector, as mentioned earlier, in the name of protecting the security and privacy of citizens’ personal data. However, data localization measures contribute very little to the purposes in pursuit, with other effective alternatives existing as well. The practice has shown that the invocation of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Article 20/GATS Article 14 is often “fruitless”. Only one of the 44 attempts to invoke the“General Exception Clause” in GATT Article 20/GATS Article 14 has been successful in defending the challenged measures.58 Furthermore, despite Chinese companies’support of data localization in India, with Alibaba, Xiaomi, and Tencent Cloud settingup local data centers in India, India banned more than 200 Chinese mobile apps by the end of 2020.59 In the name of protecting the security of citizens’ personal data, such practice has seriously violated market principles and WTO rules. In addition, Vietnam’s latest provisions on data localization, mentioned above, have been opposed by developed members of the CPTPP and boycotted by large tech companies. It is argued that such provisions are “difficult to reconcile with Vietnam’s obligations under relevant international agreements — not to restrict the use or installation of computing facilities within its territory”, and are detrimental to the digital trade development of multinational tech companies. Later, CPTPP members agreed not to sue until 2024 as Vietnam has shown the intention to put the effective date on hold.60

However, for developing countries with relatively high political sensitivity, data localization reduces data security risks, although in some cases it does not protect against data access by hostile foreign powers or organizations. Data localization measures may constitute essential security exceptions to the legal basis for restricting cross-border data flows, as set out in GATT1944 Article 21 and GATS Article 14, In the Panel Report on the Russia Cross-border Transport Case issued in 2019, the WTO Panel for the first time clarified its jurisdiction over the essential security exceptions and required that the “emergency exceptions in international relations” shall meet the time requirements for emergency, the purpose requirements for protecting essential security exceptions, and the necessity requirements between means and ends.61 However, data localization measures often take precedence over the point when an emergency occurs. For example, Russia’s data localization measures were taken before the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which effectively avoided Western cyberattacks and, therefore, inevitably failed the WTO compliance examination. During the Russo-Ukrainian War, a Russian court imposed high fines on an Amazon company for refusing to store the personal data of citizens in Russia.62 However, essential security exceptions are only “limited exceptions”, making it difficult for another country to invoke them. China’s data localization measures stem from the government’s concern for national security and the special needs of digital companies to serve the domestic market.63 Accordingly, China’s data localization measures may violate WTO obligations, and it is also uncertain whether China can join the CPTPP.

IV. Approach Development for the Realization of Digital Development Rights in Developing Countries

A. Developing countries should balance data security and openness through the WTO as a digital trade platform

In recent years, rules under compatible regional trade agreements have gradually evolved and attempts have been made to achieve a certain degree of integration between data free flow, human rights protection, and security.64 Data openness and security are by no means either-or, and good institutional tools can adjust the dynamic balance between the two. In addition, although there is no consensus among countries on the types and forms of cross-border data flows, there is more agreement on regulatory measures and the stipulation of reservations and exceptions, thus confirming the concept of “not fully theorized consensus” that “those who accept this principle donot need to agree with its requirements in specific situations”65. Given that the fragmentation of regional trade agreements can only achieve limited common interests,the WTO can play an important role in the governance of cross-border data flows.66 It recognizes the importance of protecting the interests of developing countries and integrating them into the global economy. Operating under the principle of non-discrimination, maximum conventions can be reached to better handle international rules on data flows than rules established in free trade agreements, which in essence reflect the vested interests of digital powers.67 In addition, the dispute settlement mechanism of the WTO serves as a key approach to the further development of the law. In terms of cross-border data flows and data protection, the WTO, as the world’s only multilateral trade organization, is better placed to formulate consistent, balanced, and universal rules for data-driven economies in the long run.68 Therefore, balancing data security and openness through the WTO digital trade platform is an optimal solution for developing countries to realize their digital development rights.69 India proposed that the relevant negotiations be conducted within the framework of the WTO as early as the G20 Summit in 2019. The Friends of E-commerce for Development has also been active in developing digital solutions for developing and least-developed countries to contribute to the WTO meeting outcomes.70 The negotiations of plurilateral agreements on e-commerce in 2019 involving China, the U.S., and Europe provided a platform for exploring cross-border data flows between countries. WTO members submitted more than 30 proposals since the start of the negotiations. In December 2020, the consolidated text of the WTO e-commerce negotiations was released, and the subject of cross-border data flows was categorized under Section B-2 “Information Flows”.71 With the development of developing countries’ domestic data legislation and international agreements, the WTO must establish rules for cross-border data flows for developing countries to promote sustainable development with the potential benefits of e-commerce.

1. Provisions on special and differential treatment shall be established through the WTO platform

To promote the development of global data transfer systems, countries should work more closely than ever before in bridging the digital divide in access, broadband,and technology, promoting international standards and mutual recognition schemes related to cybersecurity, addressing regulatory fragmentation, and clarifying or adjusting accountability frameworks. Special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries is an integral part of the WTO regime. The establishment of special and differential treatment will help to temporarily alleviate the digital divide and accelerate regulatory integration. Special and differential treatment means that within the multilateral trading system, taking into account the special circumstances and needs of developing countries, developing country members may, within a certain scope and under certain conditions, enjoy more preferential treatment than the general rights and obligations set out in the agreements.72 In view of the current situation of developing countries, the WTO plurilateral negotiations on e-commerce should include provisions that allow developing countries some flexibility in observing multilateral trade rules and disciplines. For example, developing countries should not be forced to suspend tariffs on electronic transmissions, although this is an essential requirement for the free flow of data. Provisions on longer transition periods shall be granted for developing countries and different transition periods shall be considered with flexibility for different developing countries according to their development levels, so that they can initiate their domestic institutional reforms before becoming fully bound by the rules, and progressively undertake higher levels of commitments over different time frames. The timetable approach adopted in the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) can be taken as a useful experience;73 Mandatory technical assistance clauses can be developed to provide capacity-building support to developing countries with insufficient technological capacity to bridge the digital divide and help them promote sustainable development through the digital economy; Assistance can be provided to developing countries for establishing legal and regulatory frameworks,giving priority to laws related to consumer protection, data protection and privacy protection to facilitate their digital capacity-building and reduce unnecessary barriers;And separate special and differential treatment clauses can be established for the least developed countries.74

2. The WTO should adopt a paradigm of provisions on cross-border data flows that are well-established and conducive to the development of developing countries

In terms of the design of digital trade provisions on cross-border data flows,countries have reached a considerable degree of consensus, not only recognizing respect for each other’s values as the basis for domestic data regulation but also embedding exceptions to the free flow of data into legitimate public policy objectives.Some developing countries have benefited from open trade agreements, but in terms of provisions on cross-border data flows, the USMCA is produced out of the weakening of data autonomy of developing countries by developed countries. The TPP(CPTPP) is the first regional agreement between developed and developing countries on data openness and security coordination. From a development perspective, the RCEP adopts a pluralistic co-governance approach between developed and developing countries, and allows for a variety of data protection measures based on recognizing the existence of a data divide, so as to provide a transitional period for developing countries to adapt to the rapid development of the digital economy in a step-by-step way.75 In addition, to accommodate the interests of less developed countries in the digital economy, the RCEP has established special and differential treatment clauses for the first time.76 Therefore, this paper holds that the RCEP is the optimal paradigm for developing countries to realize their digital development rights. In terms of the provisions on cross-border data flows, the free flow of cross-border data is adopted as the general principle, based on which contracting parties are allowed to take measures inconsistent with the principle to leave for necessary regulatory space to achieve what “they consider” to be legitimate public policy objectives and reshape their digital economy, as long as such measures do not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade. Compared to the exhaustivelist of general exceptions in the GATS, the absence of specific provisions not only facilitates WTO negotiations on cross-border data flows but also creates room for future considerations. It can build on any public policy interests that may be implicated by cross-border data flow obligations in the future, such as cybersecurity following a level-2 assessment or even technological sovereignty.77 In addition, existing digital trade agreements contain binding provisions on personal data privacy protection, which could therefore be embedded into the WTO e-commerce agreements, although efforts are still needed to minimize the privacy protection gap between countries, especially between Europe and the U.S.78 Also, countries attach great importance to the essential security interests related to data transfer, and the provisions on essential security interests in the RCEP offer an important approach for countries to strengthen regulatory autonomy. The establishment of such provisions is currently facing obstruction fromthe U.S.79

3. Regional data interoperability, accountability, and transparency should be developed during ongoing WTO negotiations

The competition in the technological arena has led to the fragmentation of the digital space, delay of technology advancement, increased complexity for the entry of users and businesses into the supply chain, and restrictions on the cross-border data flows, which have had a significant negative impact on most developing countries.80 Though reconciling privacy and cybersecurity laws across countries is a big challenge, interoperability between different regulatory systems is achievable. The greater trust and interoperability of the legal framework outweigh the restrictions on the free flow of data and the cost of complaints.81 Interoperability can help reduce barriers to entry into the digital market, enhance trust in data, and achieve mutual benefit under the premise of regulatory compatibility. The interoperability of laws and rules is an ongoing negotiation with many problems. Before that, policy interoperability, technology interoperability, and network interoperability shall be first addressed. At the same time, attention shall be paid to the technological and regulatory development and changes when addressing rule interoperability.82 The Digital Economy Agreement represents a flexible and accessible approach to realizing interoperability between digital economies at different levels of development. The WTO can learn from the experience of other international institutions, such as the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law, which adopt similar techniques in the fields of public and private international law to achieve interfaces between different regulatory frameworks.83 The Osaka Track Framework for Data Governance is based on the concept of data free flow with trust,with a strong emphasis on the trust of consumers and businesses in privacy protection and security, as well as the interoperability between different legal frameworks.84 Developing countries can make their voice heard by promoting transparency and good regulatory practices through advancing rule making and rule interoperability forcross-border data flows by organizations such as the WTO and G20.

B. China should actively promote the realization of digital development rights in developing countries.

The Chinese approach to sustainability must be taken into account when dealing with the global issue of cross-border data flows. To enhance the “institutional discourse” of developing countries, as a responsible major digital economy, China must explore unified, standardized, and inclusive global data rules that are in line with the interests of the vast majority of countries, especially developing countries, while ensuring the digital sovereignty of each country,85 realizing the compatibility of data protection frameworks with international data flows, so that developing countries can benefit from the global digital economy.

1. Promoting rulemaking cooperation under the guidance of the Global Development Initiative and Global Data Security Initiative

On September 21, 2021, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee delivered an important speech at the general debate of the United Nations General Assembly, proposing the Global Development Initiative, which, in terms of the digital sector, is to prioritize digital development, protect and promote digital human rights in development, pay attention to the special needs of developing countries, adhere to the innovation-driven approach, and focus on promoting cooperation in the digital economy field. This Initiative will provide ideas and inspiration for the digital development of developing countries, make positive contributions to the implementation of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and promote continuous, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth and social development through information and communication technologies. It should still be noted that a developing country like China is, it may make a difference in the digital sector. Therefore, when focusing on the digital development interests of developing countries, China should also design relatively favorable rules for itself from its perspective.

At the same time, China should promote development through security. To maximize consensus in the data security field, China proposed the Global Data Security Initiative in 2020, which received a positive response from ASEAN countries. On August 24, 2021, China launched the “China-Africa Joint Initiative on Building a Community with a Shared Future in Cyberspace,” proposing to explore acceptable ways to expand Internet connectivity based on respecting the cyber sovereignty of various countries, so that more developing countries and people can enjoy the development opportunities brought by the Internet. In addition, in June 2022, China and Central Asian countries reached the China + Five Central Asian Countries Data Security Cooperation Initiative, advocating the building of a community with a shared future in cyberspace. China should continue to promote data security initiatives in other developing countries to ensure a freer flow of data.

2. Promoting the “China Effect” by taking opportunities of the “Digital Silk Road” and economic and trade agreement negotiations

It should be emphasized that, compared to developed countries, China lacks cross-border legal arrangements in the digital field. So far, China has signed cooperation agreements with 16 countries to jointly build the “Digital Silk Road”, reached cooperation initiatives with 7 countries on the digital economy, and established “Silk E-commerce” cooperation mechanisms with 22 countries.86 On the one hand, there is great development room for China to cooperate with other developing countries in the digital field. The China-Africa and China-Latin America joint construction of the“Digital Silk Road” plays an important role in narrowing the digital divide and meeting the needs of information technology development. On the other hand, China still confronts groundless accusations of digital competition 87 from other countries, such as forming “digital authoritarianism”, threats to the national technology and cyber security of developing countries, overreliance from developing economies and intensifying the division of the international community.88 China also faces various challenges in aligning its systems with other developing countries. Taking data protection and circulation as an example, different data regulations will curb cross-border data flowsand hinder cooperation among digital economies. Under such circumstances, China can combine the existing practice of cooperation with developing countries, such as the cross-border data flow paradigm adopted in the RCEP, and combine the modular selection logic of the DEPA to achieve mutually beneficial cooperation with developing countries. For example, as of July 2022, China has several free trade areas under negotiation and study.89 For economies with a highly developed digital economy,given that WeChat and Douyin have successfully entered the markets of developed countries, China should promote the free flow of data based on consensus on security principles; While for developing digital economies, more attention should be paid to digital facilitation and digital infrastructure cooperation to help these countries accelerate the development of digital hardware, so as to enhance the interoperability of digital ecosystems in developing countries. In addition, in order to effectively implement more effective and targeted cross-border data flows, when negotiating bilateraltrade agreements, China can take into account the important concerns and information protection level of both countries to design a Cross-Border Transfer Cooperation Agreement, especially for the transfer of personal data and important data, as well as to reach a consensus on the issue of data sovereignty with the other country. China has already promoted cross-border data flows through the pilot free trade zones.90 For example, Chongqing and Guangxi have explored the convenient mechanism of cross-border data flows with Singapore and ASEAN countries, respectively.91

(Translated by JIANG Yu)

* LI Yanhua ( 李艳华 ), Doctoral candidate at Xiamen University and the University of Amsterdam. This paper is a preliminary result of the Chinese Government Scholarship High-level Graduate Program sponsored by China Scholarship Council (Program No. CSC202206310052).

1. UNCTAD, Digital economy report 2021-Cross-border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow, September 29, 2021, accessed April 15, 2023.

2. Zhu Yansheng, “The Evolution of the Right to Development and Approaches to its Realization: An Overview of the Human Right to Development in Developing Countries,” Journal of Xiamen University (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 3 (2001): 114.

3. From a theoretical perspective, with the rise of the expressions of “digital rights” and “digital powers,” scholars represented by Ma Changshan have proposed the concept of the “fourth generation of human rights” represented by “digital human rights.” See Ma Changshan, “The Fourth Generation of Human Rights and Their Protection in the Context of a Smart Society,” China Legal Science 5 (2019). Scholars represented by Shen Benqiu have proposed the technical empowerment, relational empowerment and institutional empowerment models of international data power. See Shen Benqiu, “The International Data Power Base of a State: AnIntroduction to China’s International Data Power Base and Development Path,” Journal of Social Sciences7 (2021). This paper discusses the digital rights of the states and data subjects within the system of the rightto development. The expression of the right to digital development was originally inspired by the realization of the right to development as a key element in data governance, as proposed by Prof. Rolf H. Weber of the University of Zurich at the Beijing Data Governance Architecture in the Digital Economy Seminar. In China,in his book The Establishment and Realization of the Right to Digital Development as an Emerging Right, Hu Jinhua first established the right to digital development “as an emerging right with the aim of realizing the digital development of human beings from the logical starting point of the development attributes of data, based on the theory of the right to development and combined with the theory of digital rights.”

4. General Assembly, June 27, 2016.

5. Karl P. Sauvant, “Transborder Data Flows and the Developing Countries,” 37 International Organization 2(1983): 371.

6. The digital divide was first proposed by American scholars to discuss information tools related to wealth, race,urban and rural areas, and access to the Internet in the United States. The global digital divide transplants the concept to the international community, highlighting the gap between developing and developed countries.See Wang Shumin, “Bridging the Global Digital Divide: Where Will the International Law Go,” Journal of Political Science and Law 6 (2021): 3.

7. Newsverge, Internet Access 19% in Developing Countries-UN report, accessed April 16, 2023.

8. UNCTAD, Digital economy report 2021-Cross-border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow, September 29, 2021, accessed April 15, 2023.

9. Prof. Nick Couldry argues that digital colonialism is a new way of allocating world resources by acquiring human experience and transforming it into data with potential economic value. The United Nations Conferenceon Trade and Development links the global digital divide with digital colonialism. For example, major techcompanies in developed countries have taken action to form national policy orientations in their favor through lobbying, infrastructure investment, and donations of hardware and software to developing countries. From China’s perspective, data colonialism refers to the process by which governments, non-governmental organizations and corporations claim ownership and privatization of data generated by their users and citizens.

10. Andrew D. Mitchell and Neha Mishra, “WTO Law and Cross-Border Data Flows,” in Big Data and Global Trade Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 91.

11. Hong Yanqing, “The Strategic Position of U.S. and Europe on Data Competition and China’s Response:Based on the Dual Perspectives of National Legislation and Economic and Trade Agreement Negotiations,”Chinese Review of International Law 6 (2021); Li Mosi, “The Game and Cooperation of Cross-Border Data Flow Rules between Europe, the U.S. and Japan,” International Business 2 (2021); Huang Zhixiong and Wei Xinyu, “The Game of Cross-border Data Flow Rules between U.S. and Europe and China’s Response: From the Perspective of the ‘Privacy Shield’ Invalidation,” Journal of Tongji University (Social Science Edition) 2(2021); Peng Yue, “Conflict and Resolution of Data Privacy Protection from the Perspective of Trade Regulation,” Journal of Comparative Law 4 (2018).

12. Julia Pohle and Thorsten Thiel, “Digital Sovereignty,” 9 Internet Policy Review 4 (2020): 8-13.

13. Mike Swift, “Data Localization Accelerates Globally as Privacy Is Linked with Data Transfer Restrictions,”accessed April 16, 2023.

14. Arindrajit Basu, “The Retreat of the Data Localization Brigade: India, Indonesia and Vietnam,” January 10,2020. A major stakeholder in the political ecosystem around the data localization debate is the Western lobbying group representing the interests of U.S. tech companies. Through collaborative efforts with industry-led lobbying groups and government-backed diplomatic endeavors, they have succeeded in pushing emergingeconomies to blur the scope of their data localization mandates and ease restrictions on the free flow of data.

15. Xu Chengjin, “CPTPP Compliance Study of the Cross-Border Data Flow Regulatory System in China,” International Economics and Trade Research 2 (2023): 72.

16. Idris Ademuyiwa and Adedeji Adeniran, “Assessing Digitization and Data Governance Issues in Africa,”CI-GI Papers No. 244-July 2020, page 7.

17. On September 23, 2022, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology,and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) published a list of foreign countries that provide adequate protection for the rights of personal data subjects, including a whitelist of 89 countries out of the 108 member states including China, India and Thailand. The updated list and the amended Personal Data Protection Law of the Russian Federation came into force on March 1, 2023.

18. If the processor transfers personal data to a foreign entity that cannot provide equally adequate protection,one of the following conditions must be met: (1) Written consent from the data subject is obtained; (2) Where international treaties to which the Russian Federation is a party provide otherwise on visa matters, and where international treaties provide otherwise on legal assistance in civil, family and criminal cases; (3) For the purpose of protecting the constitutional system of the Russian Federation and safeguarding national security; (4)Fulfillment of a contractual requirement to which the data subject is a party; (5) To protect the life, health or other vital survival interests of the personal data subject or others without obtaining their written consent.

19. The 2006 Nicaragua-Taiwan Free Trade Agreement recognizes the importance of both parties working to“maintain the free flow of cross-border data as an essential element in promoting a dynamic environment for e-commerce.” Article 14.05 (c) Nicaragua-Taiwan FTA. 2.

20. The 2014 Mexico-Panama Free Trade Agreement stipulates that each party “shall allow its personnel andthe personnel of the other party to transmit electronic data from and to its territory at the request of such personnel, in

accordance with applicable legislation on the protection of personal data and taking into account international practice.” Article 14. 10 Mexico-Panama FTA.

21. Under the EU-Mexico Modernised Global Agreement, both parties undertake to “reassess” the importance of incorporating provisions on the free flow of data within three years after the agreement takes effect. Digital Trade Chapter, Article XX EU-Mexico Modernised Global Agreement.

22. Including Chile (18), Peru (16), Colombia (12), Panama (11) and Costa Rica (11). See Rodrigo Polanco,“Regulatory Convergence of Data Rules in Latin America,” in Big Data and Global Trade Law (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 2021), 272.

23. In fact, the TPP provisions on cross-border data flows and data localization have followed those in the Additional Protocol to the Pacific Alliance Framework Agreement. On cross-border data flows: Article 13.11 PAAP; on data localization: Article 13.11 bis PAAP.

24. Affected by the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Russian parliament passed two bills ending the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Russia. See Reuters, “Russian Parliament Votes to Break with European Court of Human Rights,” accessed April 16, 2023.

25. The Chile-New Zealand-Singapore Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) modules (AI, e-identity,data flows, open data, fintech, e-invoice) are open to all countries. Digital Economy Partnership Agreement Modules, accessed April 16, 2023.

26. So far, the least developed countries in Africa such as Benin and Burkina Faso, as well as developing countries such as Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya and Nigeria, have joined the WTO negotiations on e-commerce,while important members such as South Africa still remain outside. Countries including India and South Africa argue that the WTO e-commerce moratorium has incurred revenue losses to them as it prohibits tariff imposition on electronic transmissions, and these countries initially opposed to continuing the moratoriumon tariff imposition. See K. Suneja, “Setback for India as WTO Extends Nil Tax on E-Transmissions,” The Economic Times, December 11, 2019.

27. Li Mosi, “Negotiations on WTO E-commerce Rules: Progress, Disputes and Approaches,” Wuhan University International Law Review 6 (2020), page 63. See also WTO, Communication from the Russia Federation,Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce Initiative, JOB/GC/190 (INF/ECOM/12), June 18, 2018, page 1-2.

28. WTO, Joint Statement on Electronic Commerce-Communication from Brazil, INF/ECOM/27, April 30,2019. Protecting public morals or maintaining public order; ensuring the prevention of deceptive or fraudulent practices or dealing with the impact of online contract breaches; protecting the privacy of citizens, consumers and patients in the processing and dissemination of personal data, as well as ensuring the confidentiality of personal records and accounts; ensuring safety; cyber security; resisting and preventing terrorism;combating and preventing criminal offenses.

29. Huang Jiaxing, “Fragmentation of International Digital Trade Rules: Current Situation, Causes and Countermeasures,” Pacific Journal 4 (2022): 70. The author points out in the paper that isolated fragmentation ismainly characterized by divergence of rules resulted from countries adopting different standards, while overlapping fragmentation reflects the conflict between internal and external rules brought about by dual stances,including the overlap between different free trade agreements and the overlap between free trade agreementsand WTO rules.

30. Mark Scott and Laurens Cerulus, “Europe’s New Data Protection Rules Export Privacy Standards Worldwide,” Politico, January 31, 2018, accessed April 16, 2023.

31. If agreement on e-commerce rules can’t be reached within the WTO, trade negotiations will shift to the intertwined trade agreements outside the WTO.

32. Feng Jiehan and Zhou Meng, “Regulating Cross-border Data Flows: Core Issues, International Solutions and China’s Response,” Journal of Shenzhen University (Humanities & Social Sciences) 4 (2021): 94.

33. Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them”.

34. Chander, Anupam and Uyên P. Lê, “Data Nationalism,” Emory LJ 64 (2014): 677.

35. Liu Jinhe and Cui Baoguo, “The Rationality and Trend of Data Localization and Data Defensiveness,” World Outlook 6 (2020): 104.

36. Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them,” July 19, 2021, page 7.

37. Catherine Stupp, “Ukraine Has Begun Moving Sensitive Data Outside Its Borders,” accessed April 18, 2023.

38. The report selected 42 countries from the World Bank’s category of developing countries and evaluated their readiness to manage data through four indices. Low-income economies of $995 or less have a capacity indicator of 45.1 (0-100) , an overall governance level indicator of 1.4 (0=worst, 5=best), a statistical capacity indicator of 64.0 (0-100) , and an open data index of 17.7%; The indicators for low- and middle-income economies from $996 to $3,895 are 46.1, 2.6, 75.0 and 26.8, respectively; And the indicators for middle and high-income economies from $3,896 to $12,055 are 51.8, 3.3, 76.4 and 41.2, respectively. See Susan Ariel Aaronson, “Data is Different: Why the World Needs a New Approach to Governing Cross-border Data Flows,” GWU and Centre for International Governance Innovation, accessed April 18, 2023.

39. Mary Jo Foley, Microsoft’s First African Data Centers open in Cape Town and Johannesburg, March 6, 2019, accessed April 18, 2023.

40. Internet & Jurisdiction Policy Network, We need to talk about data, chapter 3 on Data Sovereignty, Data Challenges to territorially-based sovereignty.

41. Zhao Haile, “International Legal Conflicts and Countermeasures for Personal Information Protection from the Perspective of Data Sovereignty,” Contemporary Law Review 4 (2022): 87.

42. Liu Tianjiao, “Theoretical Division and Practical Conflicts between Data Sovereignty and Long-Arm Jurisdiction,” Global Law Review 2 (2020): 185.

43. Country classification is according to United Nations, World Economic Situation and Prospects (New York:Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018). See also Chapter 1 in this volume.

44. U.S. Department of Commerce, Global Cross-Border Privacy Rules Declaration. CBPR sets highstandards for cross-border data processors through an American-style “accountability” approach and expands related business through a cross-border certification system.

45. TPP members included the U.S., Japan, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, and Vietnam. It was renamed CPTPP after the U.S. exited.

46. Zhou Nianli and Chen Huanqi, “Analysis of the Deepening and Expansion of the ‘U.S. Template’ of Digital Trade Rules Based on the USMCA,” Journal of International Trade 9 (2019): 4. Footnote 6 of USMCA 19.11states that if “it accords different treatment to data transfers solely on the basis that they are cross-border in a manner that modifies the conditions of competition to the detriment of service suppliers of another Party,”measures restricting the flow of data should not be considered as achieving a legitimate public policy objective.

47. EU Proposal for Provisions on Cross-border Data Flows and Protection of Personal Data and Privacy, accessed April 18, 2023.

48. Article 9.10 stipulates that neither Party shall require the use or installation of computing facilities by theother Party’s service providers, investors, or in such investors’ investments in the other Party’s territory as a condition for conducting business. However, a few agreements don’t have such binding clauses, such as the Argentina-Chile Free Trade Agreement mentioned earlier.

49. In the 2018 Brazil-Chile Free Trade Agreement, data localization provisions are not required as the minimum restrictive measure for a public policy objective. See Rodrigo Polanco, “Regulatory Convergence of Data Rules in Latin America,” in Big Data and Global Trade Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,2021), 289.

50. UNCTAD, Digital economy report 2021-Cross-border Data Flows and Development: For Whom the Data Flow, September 29, 2021, accessed April 15, 2023,

51. “Location of Computing Facilities” in CPTPP Article 14 and “Cross-border Transfer of Information through Electronic Means” in CPTPP Article 15.

52. Yakovleva and Svetlana, Three Data Realms: Convergence or Competition (Februray 7, 2022). Amsterdam Law School Research Paper No. 2022-58, Institute for Information Law Research Paper No. 2022-13, page 13.

53. Following the Schrems case, the EDPB, through its unofficial report, examined information on Chinese, Indian and Russian legislation and practices regarding government access to data, and concluded that they conferbroad

interpretations and exemptions for security and public order with no substantial protection for government access to data. See Milieu, KU LEUVEN, “Legal Study on Government Access to Data in Third Countries,”

54. Li Mosi, “China-EU Cross-border Data Flows Cooperation in the Context of China-U.S.-EU Triangle Game,” Chinese Journal of European Studies 12 (2021): 6.

55. The Economist, “How China Inc is Tackling the TikTok Problem,” accessed March 7, 2023.