Rural poverty and digital inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean: a case study from the provinces of Salta - Argentina

Maria Francesca Staiano (Argentina)

Introduction

Poverty is a multicausal phenomenon and, therefore, multidimensional. In fact, Spicker (2009) reconstructs twelve definitions of the term "poverty", which point out different aspects of it. The definitions correspond to different conceptions about this concept, which the author divides into three main currents: those that point to the lack of material conditions, those linked to economic deficiencies and those that link poverty with social aspects.

Under the material concept, poverty is defined as the lack of material goods or services, that is, it represents a core of basic needs and a set of other needs that change over time and space (George, 1988); poverty, in this sense, is a severe deprivation of physical and mental well-being that is not connected with economic resources and consumption (Baratz and Grigsby, 1971). From the economic perspective, poverty is related to the standard of living, that is, living with less than others. The International Labor Organization (ILO) considers that "at the most basic level, individuals and families are considered poor when their standard of living, measured in terms of income or consumption, is below a specific standard" (ILO, 1995). Subsequently, the situation of inequality was also considered as poverty: people can be considered poor because they are in a disadvantaged situation compared to others in society (Miliband, 1974). According to the social concept, poverty is related to the absence of entitlements, lack of basic security, exclusion, dependency and social class.

In 1980, the World Bank defined poverty from the perspective of deprivation; it extended the purely material lack to the social, spiritual and cultural levels. In 1990, the “Human Development Report” presented for the first time the concept of “human poverty”, which indicated that human poverty was not only one of income, but that it was the essential capacity to lead an acceptable life (World Bank, 1990). This new concept of human poverty puts general attention on human development and opens the prelude to research on “multidimensional poverty”. Later, in the “1997 Human Development Report”, another new concept was proposed: Human Poverty Index (HPI), which does not use income to measure poverty, but rather the most basic description and expression of poverty indicators, such as short life and premature death, lack of basic education and inaccessible resources. In 2010, the UN development program reiterated the connotation of human development after summarizing the experiences of the previous stage, and updated the poverty measurement indicator, which is the GDP, with the three dimensions: health, education and standard of living; its focus is to identify the multidimensional deprivation suffered by families.

There are classic and contemporary studies that allow us to approach the study of the phenomena of poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean. Among them, one of the most important is that of Altimir (1979), which not only investigates the dimensions of poverty but also provides us with different methods for drawing poverty lines.

More recently, Stavenhagen (1998) has published a classic article that provides general considerations on poverty in Latin America, while Gasparini, Cicowiez and Sosa Escudero (2012) provide inputs to relate poverty, inequality and growth. On the other hand, Gacitúa, Sojo and Davis (2000) analyze the link between poverty and social exclusion. Filguera and Peri (2004), meanwhile, incorporate the dimension of vulnerability and risk structure. In turn, Rosenbluth (1994) links poverty and informality, providing a necessary perspective to analyze poverty in contexts of economic and social crisis.

Echeverría and Reca (1998) have published an extremely interesting book on the relationship between agriculture, the environment and rural poverty, while Perfetti del Corral (2009) has analyzed rural poverty in crisis contexts. Hall and Patrinos (2006), meanwhile, studied poverty and inequality in rural indigenous peoples.

Finally, there are works that have analyzed the impact of ICTs on poverty reduction, such as Rodriguez and Sánchez Riofrío (2017).

On the other hand, there are works that carry out case studies and that will be useful, such as the one published by Villatoro (2004) within the framework of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC or CEPAL in Spanish). In turn, Raczynski (1995) has published a work within the framework of the Inter-American Development Bank that presents strategies to combat poverty based on specific programs, institutions and resources.

In such an articulated theoretical-methodological framework, the objective of this analysis is to systematize the information about the peculiarities of poverty in the Latin American continent and to analyze in detail the development of national and provincial policies in Argentina, emphasizing the case -Study of the Horus project in the province of Salta.

1. Poverty in Latin America. Current situation.

Poverty is a widespread, structural and multi-causal phenomenon in Latin America and the Caribbean. In fact, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America, the region is one of the poorest in the world. Luo and Wang (2022) point out that, from 2000 to 2014, due to the great advances made in the governance of poverty, the proportion of poverty was reduced from 45.4% (230 million people) in 2002 to 27.8% (164 million people) in 2014, while the proportion of extreme poverty decreased from 12.2% (62 million) to 7.8% (46 million) in the same period. However, starting in 2015, this trend slowed down, and even plateaued and picked up.

According to ECLAC data, by 2021 in the region 31.1% of people live in poverty, while 13.8% are in extreme poverty; that is, almost 1 out of every 2 Latin Americans does not have decent living conditions.

The Covid-19 pandemic has substantially aggravated the situation. According to data from the World Bank, Latin American economies fell 6.7% as a whole in 2020, representing the largest drop in the world for the same region. In this sense, of the 20 economies that fell the most worldwide, ten are Latin American. The economic growth of the region in 2021, of 6.8%, meant a partial recovery of the losses caused by the pandemic, but it did not reflect growth compared to the numbers of 2019.

In turn, according to the prospects of the International Monetary Fund, the economic damage caused by the conflict in Ukraine will contribute to a significant slowdown in global growth in 2022, a period in which fuel and food prices have risen rapidly, hitting a particularly heavy blow to vulnerable populations in low-income countries.

In this framework, according to the World Bank, five million more people on the continent entered extreme poverty in 2021, and it has already reached 86 million people, while 201 million are below the poverty line. The largest increases in poverty took place in Argentina, Colombia and Peru, where they reached or exceeded 7 percentage points. In Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Paraguay it grew between 3 and 5 percentage points and in Bolivia, Mexico and the Dominican Republic, it grew by less than 2 percentage points (UN, 2020).

In turn, according to ECLAC, the crisis has also highlighted the vulnerability in which a large part of the population lives in the middle-income strata, characterized by low levels of contribution to contributory social protection and very low coverage of social non-contributory protection.

In other words, in addition to the persistence of households in a situation of structural poverty, there is a large number of households that have temporarily been able to escape from poverty, but which are also in a situation of great vulnerability and instability. This is combined with the fact that Latin America and the Caribbean is one of the most unequal regions in the world and, according to the World Bank's Gini Index, 16 countries in the region are among the 25 most unequal in the world. The foregoing has repercussions in that economic growth (measured in the interannual GDP performance) is not necessarily linked to an equitable distribution of resources; in fact, in times of economic instability such as the one the international system is going through, poor populations end up bearing the brunt of the crisis.

The large number of households in a situation of poverty means that it has a multidimensional character and, in turn, that there is a multiplicity of situations to attend to when addressing the phenomenon. First, in Latin America and the Caribbean the urbanization rate is above 80%, much higher than the global average of 56%. At one extreme, we have the cases of Argentina (92% of urban population), Venezuela (88%), Chile (88%), Brazil (87%), Colombia (81%), Mexico (81%), among others. On the other hand, there are also cases of countries with a high percentage of rural population, such as Saint Lucia (79% of rural population), Antigua and Barbuda (76%) or Guyana (73%).

However, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2021), the rural poverty rate rose to 48.6% (59 million people) and the extreme rural poverty rate to 22.5 % (27 million). In this sense, the rural poverty rate doubles that of urban poverty, while extreme rural poverty is almost triple. According to the same FAO report, being born in a rural area not only brings with it a structural inequality with respect to urban space, but this is also accentuated in the case of women.

The economic slowdown in most of the countries of the Latin American region, added to the disarticulation of sectoral and social policies focused on the countryside, have been the main causes of the increase in rural poverty. Added to this, climate vulnerability and the expansion of agribusiness have forced thousands of families to migrate to large urban centers.

2. Public policies in Argentina during the COVID-19 pandemic

Historically, and as a tradition in Argentina, those who found themselves in unfavorable conditions or in poverty in rural areas forcibly migrated to the big cities in search of work and a better quality of life. For this reason (and others as well) is that the great urban conglomerates were formed around the cities of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Mendoza and Rosario. Therefore, rural poverty and its consequences are not foreign to the country, even more so when it doubles the rate of urban poverty.

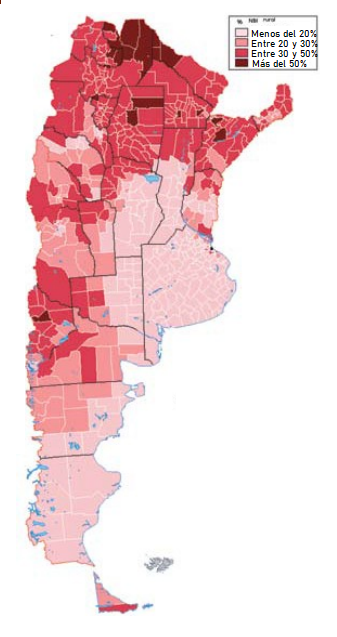

Map no. 1. Percentage of rural poverty in Argentina.

Source: Román y Monzón (2011)

Currently, and without prejudice to the internal migratory processes that occurred in Argentine history, the problem is strongly concentrated in the north of the country, particularly in the provinces of Formosa, Salta and Jujuy; and also in the north of the province of Santiago del Estero, Corrientes and Neuquén (see Map n°1). However, in the same way we find rural poverty in various parts of the map, to a lesser extent, throughout the north (northwest and northeast) and in the west (provinces of Neuquén, Mendoza, Río Negro and La Pampa).

However, until the current century, Argentina has not had a tradition of implementing strong public policies aimed at developing family farming producers and/or native communities. On the contrary, it has always been characterized by concentrating the political debate on medium and large agricultural products that, according to their characteristics and resources, are afflicted by other problems that are very different from those that suffer from rural poverty.

However, at the beginning of this millennium, Argentina began a process of approving laws and developing specific policies for this issue, which is new and interesting for the national tradition. Regarding the legal and political framework, the problem of rural poverty has been approached from "family, peasant and indigenous agriculture". In other words, it seeks to alleviate rural poverty through the application of policies for the development of activity in rural areas, concentrating on three specific groups: the peasant producer, the group of producers that are grouped together in a family regime or those who work under an indigenous community regime. To this end, various regulations have been issued to promote rural development.

3. The Province of Salta in Argentina and the use of technology as a tool to combat poverty: The Horus Project.

According to a report from the Information, Evaluation and Monitoring System for Social Programs (SIEMPO, in Spanish) of the nation State, Salta is one of the Argentine provinces with the highest levels of poverty in the country. In the second quarter of 2019, 43.9% of the population was below the poverty line, which placed it 7.5% percentage points above the national average. At the same time, 5.7% of the population in Salta was homeless, that is, their income was not enough to cover the basic food basket. Meanwhile, in Salta, 7.9% of the population up to 6 years old was homeless and 56.6% lived in poverty. In turn, the percentage of rural poverty has risen to more than 50% in that province.

3.a. General aspects

In 2016, the province of Salta, Argentina, through the Ministry of Early Childhood, created a program to combat poverty, specifically to combat child malnutrition in remote areas through the use of ICT’s. The project can be developed through an innovative partnership between local government, private entities and non-governmental organizations. The Ministry of Early Childhood of the Province of Salta was the first ministry dedicated exclusively to this in Latin America.

Through tablets and apps, data is collected from house to house and person to person in certain regions, the project was initially called “Technological Platform for Social Intervention”. These data are georeferenced, tabulated and validated by the ministry, and then made available in real time to public or private institutions so that they can contribute to the fight against poverty. All this information is placed in a central control system that allows public institutions to direct efforts immediately.

This action allows public or private institutions to quickly approach the population, avoiding citizens having to go to where services are available, which often does not happen due to management costs. The information collected had an initial focus on early childhood, alert systems help the State to act more effectively in the fight against vulnerabilities, but this data can help in the construction of several individual policies to combat poverty. After all, the fight against malnutrition, for example, has several forms.

The system developed by the participants allows public institutions to also improve their service. For example, by receiving information, a public institution can better plan the form and frequency of its visits to people at risk, it allows public education institutions to better focus on different plans for early childhood education, such as the number of places in kindergartens or vocational education and even health issues, such as improving nutrition projects for children and pregnant women.

In addition, the system links activities among all members of the public sector to identify who should act in a particular region where an alert has been activated. This crossing of data makes it possible to predict vulnerabilities and anticipate specific actions. In the way, the provincial government can develop personalized public policies, avoid intermediaries and act directly with the most vulnerable families.

Working teams from the Ministry of Early Childhood of Salta interviewed more than 300,000 people in the most vulnerable areas of the region, which made it possible to generate public policies focused on each of the problems analyzed by the data, with a greater focus on childhood and early childhood. The work is carried out with the support of third sector organizations. According to the government of Salta, there is a georeferencing and individualization of all children at risk in the province and this has allowed a significant reduction in infant and maternal mortality.

The project draws attention because it uses technology to collect data and build information that can help identify localized problems and avoid errors in the construction of public policies to combat poverty (Lafuente, 2016). Furthermore, it is interesting to observe the participation of other organizations, outside the State, in the construction of actions to combat poverty, something rarely seen so far. However,as much as it attracts attention and is an innovative project in the field of combating poverty, there are strong criticisms of the project and the way it was carried out.

3.b. Criticisms and reflections about the project

Criticisms of the Horus project in the province of Salta are observed from three angles. The first one, refers to the issue of the use of artificial intelligence and personal data, a common discussion in an increasingly technological world that is interconnected with the role played by large IT companies. The second one, of greater scope, refers to issues linked to the State, such as the evaluation of the impacts of the project and even the conduct of the project with the change of government. Finally, the negative approach to the issues involving adolescent women and adolescent pregnancy is discussed.

Couldry and Magalhaes (2021) state that this project uses artificial intelligence to permanently monitor children and women in precarious social conditions for the construction of algorithmic knowledge that allows the government to predict characteristics that lead to problems and act in advance.

In this sense, there are some criticisms of the use of artificial intelligence to build this data, for Peña and Varon (2019) this project uses total surveillance of vulnerable people and generates technical and evaluation errors. The authors recall that even in 2018 the data was only for women and that there was an initial focus on combating teenage pregnancy and school dropout, which generated a distorted view of reality (ICC, 2018).

Regarding the problems with artificial intelligence, Peña and Varon state that the use of this technology to combat poverty has grown in the world, such as the use of algorithms to make decisions about the distribution of services and investments in areas such as education, public health, housing, etc (2019: 29). However, Cathy O’Neil’s reflections show that these systems end up punishing the poor and not helping them, precisely because they are subject to errors and can generate stigmatization, discrimination and even the criminalization of vulnerable people.

The Applied Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of the Buenos Aires University (UBA, in Spanish) (LIAA, 2018), issued a report in 2018 evaluating the project and highlighting some technical errors, specially when there was still a focus on combating teenage pregnancy and school dropout, such as the collection of inadequate or insufficient data for the evaluation of this problem, unreliable data and with some mistakes, and the significant increase of some information, which would produce incorrect results and lead the authorities to take actions and develop mistaken public policies.

Based on these misconceptions, Sternik (2018) called the idea of “intelligence that does not think” and brings up an important point regarding the discussion on the use of artificial intelligence: personal data. As it is a project that captures personal data and uploads it to the clouds, there is a concern about the security of this data and the way it will be treated by the government and the organizations involved.

Microsoft, creator of artificial intelligence, affirms that the data is safe on its platform (Microsoft, 2018), but Beatriz Busaniche from Fundación Via Libre (Sternik, 2018) recalls Act Nro. 25,326, which deals with the protection of personal data, and points out that the legislation imposes special protection on vulnerable groups and prohibits the collection of sensitive data (Section 7, paragraph 3) which states that:

“The formation of files, banks or records that store information that directly or indirectly reveals sensitive data. Religious organizations and political and trade union organizations may keep a register of their members”.

Other criticisms come from authors such as Fernández and Herrera (s/f) who claim that some data disappeared with the changes in government and the ministry itself ceased to exist. The main point of this discussion is the question of how the work was carried out after the change of government, first the Ministry of Early Childhood, the body responsible for the project, ceased to exist. Also, according to current government officials, some of the project data was not approved at the time of the government transition. Other complaints are based on the idea that the former managers used the project personally and began working on it through the private sector.

In recent years, the project has been plagued by some allegations of corruption involving former directors. It is important to point out that the Horus Project was built as an innovation in the fight against poverty of vulnerable groups and became an example for several countries in the region, but several subsequent mistakes put the project in check.

3.c. National and international interest

In 2018, the government of the province of Salta claimed to have increased the number of early childhood centers by more than 200%, according to data generated by the Horus Project, which led to the project being taken to some provinces in the country. The project has attracted worldwide attention, even being reproduced in several Latin American countries such as Paraguay, Colombia, Bolivia and Brazil, and being studied by MIT and other institutions.

In 2019, Brazil signed an alliance to create the “Happy Child” project through its Ministry of Citizenship (Governo Federal, s/f). The project is already in the testing phase in medium-sized cities in the northeast of the country.

3.d. Reflections on the Horus Project

The Horus project is an important initiative that links government and private entities with the use of technology to combat the poverty of the most vulnerable, specially children and adolescents. It is part of a very important issue and has an objective that draws attention, after all, the use of technology and innovation for policies to combat poverty is necessary in this post-pandemic moment and should not be left aside.

However, the criticisms raised by social organizations also cause important attention flags to be seen, mainly because significant data is available and online, a discussion that has grown in the world. Thinking from the point of view that public policies are built from a path of mistakes and successes, of trials and failures. The Horus Project is important for these discussions to arise and for future experiences to avoid making the same mistakes.

Also, it is striking how political and transparency issues continue to interfere with the continuity of projects and public policies in the region, a problem not only in Argentina, but in all of Latin America. A major challenge of the investigation was to obtain up-to-date data on the Horus project and its impacts, but the investigation found that this was also a challenge for the government itself.

4. Conclusions

In recent years, studies on absolute and relative poverty have undoubtedly affirmed the indissoluble link between poverty and inequality. From a socioeconomic point of view, we can affirm that poverty is the product of inequality because it is a consequence of inequalities in income, wealth, class, gender, and race, generating an intersectionality of constant social discrimination (Stezano, 2021). In fact, at the normative level, it has been perfectly considered how poverty is, in practice, a serious and systematic violation of the possibility of fully exercising economic, social and cultural rights (Mancini, 2018).

This particular category of human rights, strongly linked to economic and human development, is now going through a serious post-pandemic crisis due to the concentration of wealth in a small group of an elite more attentive to a financialization of profit than to a reduction in inequality. According to the ECLAC report on Poverty 2021, “the constant growth of inequality in the last three decades has been, more than an unexpected result, an option. This option has been enshrined through certain policies chosen by governments: the margins and limits of capital mobility, the imposition of austerity behaviors in public spending and the levels of market deregulation. These policies have led to (often modest) growth, but above all they have increased inequality” (Stezano, 2021).

In this sense, objective 17 of the Sustainable Development Goals, "Strengthen the means of execution and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development", recalls in its sub-goal 17.16: "Improve the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, in order to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in all countries, particularly developing countries.” Global governance based on the realization of fundamental rights, such as freedom from poverty and hunger, is a crucial issue when implementing national and local programs.

Poverty, in all its definitions, meanings, peculiarities and manifestations, beyond any scientific characterization, represents a failure of humanity. In this document it became clear that this is a complete phenomenon. For this reason, it must be addressed as such, through strategic actions in synergy between local, provincial and national governments and within global governance. Only through an in-depth study of the characteristics of local variables and within a framework of international cooperation can we hope to achieve human development that reaches an acceptable global standard.

Therefore, we must consider the small case study of the province of Salta, Argentina (albeit with all its contradictions) as a starting point and an end point of international cooperation so that peoples are not subjected to poverty and inequality. The starting point is a meticulous study, house by house, to closely resolve one of the most serious situations of poverty in the country, through the principle of subsidiarity of Argentine institutions. But also the final point of a broader discourse, global in scope, that cannot be postponed: international cooperation as the only tool that can promote human, peaceful and sustainable development, through an exchange of good practices.