Human Rights in Civil Judicial Documents: Conception and Function

ZHENG Ruohan*

Abstract: Traditional human rights theory tends to hold that human rights should be aimed at defending public authority and that the legal issue of human rights is a matter of public law. However, the development of human rights concepts and practices is not just confined to this. A textual search shows that the term “human rights” exists widely in China’s civil judicial documents. Among the 3,412 civil judicial documents we researched, the concept of “human rights” penetrates all kinds of disputes in lawsuits, ranging from property rights, contracts, labor, and torts to marital property, which is embedded in both the claims of the parties concerned and the reasoning of judges. Human rights have become the discourse and yardstick for understanding and evaluating social behavior. The widespread use of the term “human rights” in civil judicial documents reflects at least three concepts related to human rights: first, the rights to subsistence and development are the primary basic human rights; second, the judicial protection of human rights is a bottom-line guarantee; third, the protection of human rights aims to achieve equal rights. Today, judges quote the theory of human rights in judicial judgments from time to time, evidencing that human rights have a practical function in judicial adjudication activities, and in practice this is mainly anifested in declaring righteous values and strengthening arguments with the values and ideas related to human rights, using the provisions concerning human rights in the Constitution to interpret the constitutionality, and using the principles of human rights to interpret blurred rules and rank the importance of different rights.

Keywords: human rights · concept of human rights · civil judicature · judicial documents · judicial reasons

It seems to be common sense that human rights as legal rights should be judicially guaranteed. But we are unfamiliar with how human rights as discourse are presented in justice, especially civil judicature. Civil judicial documents happen to contain important clues and materials.

I. Contrary to Common Sense: “Human Rights” in Civil Judicature

There is a popular judgment in the field of human rights law that only the State (government) is the subject of human rights obligations, and thus legal issues relating to human rights are generally considered to fall under the category of public law. This judgment is rooted in the classic concept and philosophy of human rights in modern times. Regardless of the differences in the assumptions of human nature by Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke and Rousseau, the ideological interest of “the concept of innate human rights as political rhetoric”1 contains vigilance against the power of the monarch or government. The trend of individualism and the philosophy of subjectivity formed out of it advocate the autonomy of the individual, emphasize the realization of individual free will, and stress that the individual should exclude the interference of external factors such as others, society, and state.2 In fact, in the early texts of classic human rights, human rights were always concerned with public law principles such as due diligence in taxation and due process of law or were meant to express implicitly or plainly the demand for defense against central power or public power. When human rights are embodied as basic constitutional rights, the right to defense is its core power,3 and defense against public power (rather than private power) is its most common function. Even beyond the perspective of sovereign states, the defensive and confrontational logic of human rights seen in the field of public international law theory and practice remains consistent. As Joseph Raz puts it: “Human rights are the right to morally justify the means of limiting sovereignty.”4

However, the development of human rights concepts and practices has not always evolved in only one direction. After the Second World War, with the rise of human rights movements in European countries, the impact of basic human rights on the development of private law in Europe gradually became profound.5 The object of constraint on human rights and fundamental rights began to expand from the family to the private sector.6 Several civil judicial cases and the legal precedents by the European Court of Human Rights demonstrated this trend.7 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which is the consensus on international human rights, does not limit the subject of human rights obligations to the State (government), and only one right in the Declaration is one relative to the State (social security). At the same time, Article 29 of the Declaration clearly emphasizes that “everyone has duties to the community,” and the subject of the obligation is not limited to the State (government). Moreover, based on general human rights principles, it is unfair to deliberately distinguish between the perpetrators of a violation to determine whether it constitutes a violation of human rights, since, in any event, victims cannot be discriminated against because the nature of the violation is “private.”8 In this regard, although civil judicature is inconsistent with our traditional understanding of human rights, it conforms to the intrinsic value orientation and development trend of human rights and therefore should be taken seriously.

In China’s judicial practice, there are also signs of human rights entering private law. Of course, human rights mostly intervene in private law in the name of specific rights, and the term “human rights” seems redundant. However, a textual search shows that the term “human rights” exists widely in China’s civil judicial documents. Existing research has not paid sufficient attention to this. This article will examine the civil judicial documents, analyze the concept of Chinese rights reflected in them, and reveal the functional role of human rights in civil judicial adjudication.

II. An Overview: Human Rights in Civil Judicial Documents

In this paper, we searched on PKULaw.com for judicial documents by setting the search conditions as follows: the time span: January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2021; the cause of action: “civil”; and the keyword: “human rights”; scope: full texts. The search generated a total of 376,348 judicial documents. To exclude non-directly related judgments containing the Chinese words “creditor’s rights,” “parties’ rights” and “debtor’s rights.”9 A second was conducted sample screening through Python programming which obtained a total of 3,412 judicial documents containing the term “human rights”.

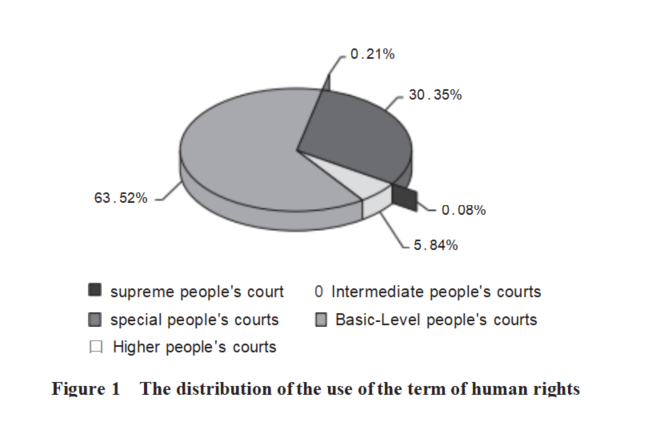

A. Distribution of Trial Levels

From the statistical sample (as shown in Figure 1), the distribution of trial levels shows a clear pyramid-shaped structure, and the civil judicial documents of the basic-level people’s courts account for the highest proportion (63.52 percent) of the total sample. Although this is related to the huge volume of the judicial documents of the basic-level people’s courts, it does not lack significance. After the release of the white paper The Human Rights Situation in China in 1991, the concept of “human rights” was officially widely used and became a “great term”;10 and in 2004, “the state

respects and protects human rights” was included in the Constitution. The concept of human rights was further desensitized. However, it is undeniable that for a long period of time, the lower-level judicial and administrative institutions adopted more cautious attitudes towards “human rights”; and it was common to “avoid reference” and “respectfully distance themselves from it.” See Figure 1.

To a certain extent, the frequent use of the term human rights in the civil judicial documents of basic-level people’s courts is a positive sign. In other words, it is not only the high-level people’s courts with higher authority that dare to handle “human rights,” and basic-level people’s courts adopt an open attitude toward human rights. At the same time, we found that 66.1 percent of the judicial document samples by basic-level people’s courts used the term “human rights,” which shows that the use of the term in judicial documents is not only on the basic level but also popular. No matter in what sense the concept of human rights is used, it has entered the public eye and become a term for the public to understand law, fairness, and justice, which is in line with the popularization of human rights in Chinese society.

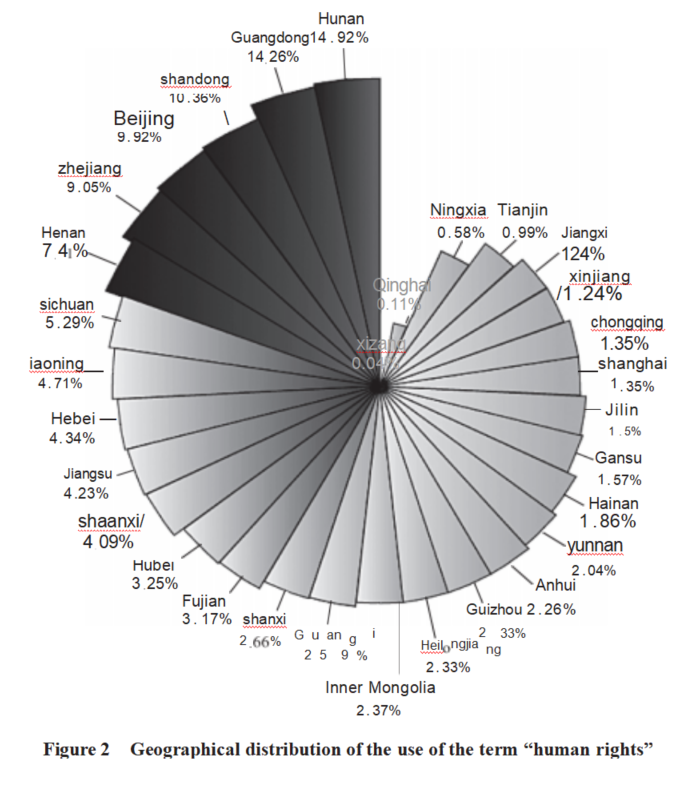

B. Regional distribution

The regional distribution by provincial administrative regions doesn’t show significant regularity. The only certain thing is that the term has entered the civil judicial documents of the 31 provincial-level administrative regions (Figure 2). In addition, from a very superficial perspective, the proportion of the sample documents in the central and eastern regions is generally larger than that in the western region. This suggests that, to a degree, the level of economic and social development is correlated with the acceptance of the concept of human rights. However, a closer look at the specific content of the judicial documents shows that the sample data does not suffice in establishing this correlation, but it reveals some special and additional information. Most samples (14.92 percent) were from Hunan Province. However, in the sample documents, the extensive use of the term “human rights” by Hunan’s basic-level courts stems from the use of “templates” in the trials of similar cases (see Figure 2). In other words, many basic-level people’s courts in Hunan make the following reference when hearing cases involving compensation for collective land expropriation: “Compensation for land expropriation is in nature compensation for rural collective land ownership, is based on status and membership, and is the protection of basic human rights.” Such “templates” are not even limited to Hunan itself. “The acquisition and loss of membership in rural collective economic organizations are not stipulated in the law, but the Constitution stipulates that ‘the state respects and protects human rights.’”11 Similar expressions can be found in civil judgments in Henan province and other places. For judges, using “templates” is a labor-saving and prudent move. But it should also be realized that reasoning based on human rights can be used as “templates” because judges believe that the term can enhance the authority of judgments and produce persuasiveness for the parties. This further shows that “human rights” as a reason is significant both among judges and the public.

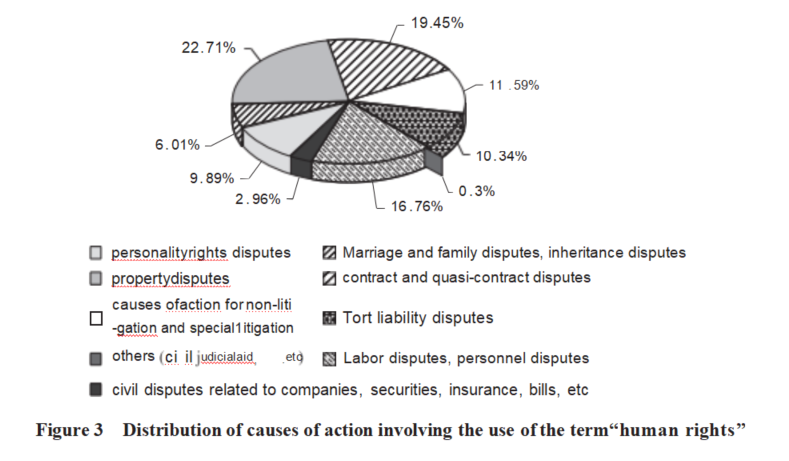

C. The distribution of causes of action

From the statistical sample (Figure 3), the use of the term “human rights” in civil judicial documents is more concentrated in property rights disputes, contract disputes, tort liability disputes, labor disputes, personality rights disputes, matrimonial property disputes, non-litigation procedures and special litigation causes (especially objections to enforcement actions). This is also reflected in aid cases in civil judicature.

Among the property rights disputes, contract disputes, and labor disputes (accounting for nearly 60 percent of the total), the term “human rights” mostly focuses on “survival interests” or “survival rights.” Typical expressions such as “the reason why the Official Written Reply makes the rights of consumers buying houses a privilege is that this right involves consumers’ right to subsistence; and the right to subsistence as a basic human right should be superior to business rights such as mortgage rights,”12 “the right to contract rural land involves the right to the subsistence of farmers, which is a basic human right.”13

In labor disputes, in addition to focusing on the right to subsistence, the right to rest is also upheld, such as “the right to rest is a legal right of workers and a basic human right.”14 Tort liability disputes are mainly over the right to reputation, life, health, and body. Typical expressions such as “the right to subsistence is the supreme basic human right, and no one can illegally deprive others of their right to subsistence.”15In general, the use of the term “human rights” is widely distributed in civil cases, and the idea of human rights has positively permeated the law system.16

It is worth noting that in the sample documents distributed in various causes of action, in addition to carefully prepared “official” expressions, there are also many popular understandings and expressions. In the eyes of the parties, the impact of new buildings on daylighting, ventilation, etc. is “infringing the plaintiff’s human rights.”17 An imparity clause “violates my human rights.”18 If the employer contributes to the “five insurances and one housing fund” without having confirmed the insurance base with the employee, and “forged my signature, this violates my human rights.”19 Even in divorce disputes, the perceived situation in which “the plaintiff’s parents interfered with the defendant’s family and caused trouble out of nothing, and this resulted in disagreements and disputes between the husband and wife” was considered “a violation of human rights.”20 In this regard, whether or not the concept of human rights is used by the public “accurately,” the idea of human rights is no longer a shelved academic concept or an abstract term alienated from public social life, and they have entered the realm of public awareness.

III. The Concept of Human Rights Reflected in the Use of the Term “Human Rights” in Civil Judicature

The use of legal concepts in judicial decisions is always based on legal norms, often with definite semantic boundaries. At the same time, although concepts regarded as principles or values such as human rights, freedom, and equality also have conventional semantics, their connotations are subject to interpretation, and their true, complete, or general meanings are not completely and directly defined by law. The socially held understanding and perception also give it implicit reason and meaning. In other words, the use of the concept of human rights in judicial documents not only reveals its legal meaning but also conveys some ideas about human rights that have been accepted by society.

A. The rights to subsistence and development are the primary basic human rights

Since 1991, when China issued its first human rights white paper entitled The Human Rights Situation in China, the idea that “the right to subsistence is the primary human right” has become part of China’s consistent discourse on human rights. “Without the right to subsistence, there would be no other human rights.”21 Of course, the concept of human rights always reflects a specific historical stage of development. The right to subsistence described in detail in The Human Rights Situation in China is concerned with problems faced by the people in their struggle for independence, such as life, food, and clothing. Moreover, the discourse of the right to subsistence at that time was more related to the collective human right in the sense of a state and a nation. After the white paper entitled Progress of Human Rights in China was released in 1995, the right to subsistence is no longer rooted in the context of national independence and instead associated with the right to development. The idea that “the right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights” has always been conspicuously reflected in the human rights white papers over the years. This discourse, which continuously gains official recognition and appears frequently in various media, reflects and shapes the Chinese understanding of human rights. This has been clearly shown in judicial decisions.

In civil judicial documents, the concept of “the right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights” is more reflected as the “right to subsistence,”22 which is most commonly found in agriculture-related disputes. For example, in the second instance of a dispute over the rights and interests of members of a collective economic organization, the appellant said: “Land, as the most basic means of production and subsistence for members of rural collective economic organizations, functions as a basic survival guarantee, and guarantees the basic right to the subsistence of farmers. It is also the fundamental expression of human rights.” In the appellant’s view, the right to membership in a rural collective economic rganization is concerned with the member’s life, and therefore related to the basic right to subsistence, which is precisely the fundamental embodiment of human rights. Similar concepts are reflected in the causes of action for a labor dispute: “Article 33 of the Constitution states that the state shall respect and protect human rights. The most basic human right is the right to subsistence. I am a veteran and an ordinary laborer who relies on labor to support my family. The factory deprived me of my labor rights without any reason, leaving me with a life of loneliness and a broken family. This not only seriously violated the minimum right to subsistence I enjoy as a citizen but also violated the basic spirit of the Constitution.”23

Of course, such a concept is not only the parties’ simplified understanding of human rights, but also judicial reasons for judges to adjudicate similar issues. The judicial “templates” mentioned above being a typical example: “The acquisition and loss of membership in rural collective economic organizations are not stipulated in the law, but the Constitution stipulates that ‘the state respects and protects human rights’, and the right to subsistence is a basic human right.”24 In land disputes, judges also adhered to a similar concept, believing that “the right to contract land management is an important part of rural production relations, a basic human right of farmers protected by law, and a guarantee for their livelihood.”25 The idea that “the right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights” is also reflected in disputes that are concerned with subsistence. For example, in a dispute over the right to abode after divorce, the judge found that the appellant’s demand for the elderly and sick appellee to be immediately removed from the disputed house would “in fact deprive him of the most basic right to subsistence” because “the right to subsistence is the most basic human right, and the Constitution stipulates that the state respects and protects basic human rights of citizens”.26 In addition, in some judicial aid decisions, judges clearly stated: This Judicial Aid Committee believes that the main purpose of the state’s judicial aid is to protect the parties’ basic human rights such as the right to subsistence and the right to development. This shows that the idea that “the right to subsistence (the right to development) is the most basic human right” has become part of the civil judicature; and that this concept is supported by the consensus of both judges and parties, and is an easily accepted and even “useful” reason.

B. Judicial protection of human rights is a bottom-line guarantee

There is always ambiguity in the connotation and extension of human rights, and the public’s concept of human rights is different from that of human rights in legal practice. If there is a large overlap between the two, human rights are a “living” concept that can be effectively implemented. Conversely, if the two are far apart, human rights are reduced to an empty and ambiguous term. In civil judicature, although the expression of the public’s concept of human rights lacks legal rigor, and the concept of human rights in the eyes of legal adjudicators is far narrower than the public’s understanding, the two maintain a cognitive and logical tacit understanding to a certain extent. In other words, the judicial protection of human rights is a bottom-line guarantee.

In a dispute over reputation rights, the plaintiff asserted: “The defendant’s unbearable malicious words and deeds to the plaintiff caused great mental harm and losses to the elderly plaintiff and his family, and openly run afoul of the important principle of our Constitution, which states that ‘the state respects and protects human rights.’”27 In the plaintiff’s view, human rights are a bottom-line guarantee for human dignity. In a dispute over the cost of upbringing, the appellant stated: “the enforcement of the first-instance judgment, carried out knowing that the appellant is unable to pay, may jeopardize the appellant’s current family stability and seriously affect the minimum living security and the most basic human rights of the appellant, the appellant’s mother, and the family.”28 Here, human rights are a bottom-line condition for the appellant. Similarly, in a tort liability dispute, the appellant asked: “Where is the human right if the only dwelling is demolished without having made arrangements for resettlement?”29 In short, in the above-mentioned cases, regardless of whether the parties’ application of the concept of human rights is legally supported, in their inherent and simplified concepts, human rights violations are always associated with serious damage to the spirit or grave impact on material life.

Judges do not use the concept of human rights as broadly as the parties to the disputes, but their use of human rights often expresses or implies a view of human rights aimed at achieving bottom-line protection. The most typical case is the above-mentioned one in which the judge believed that “the right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights”. This also recognizes that the value of human subsistence is the minimum human rights value.30 In addition, the concept of bottom-line protection is more commonly seen in tort disputes involving personal injury compensation and labor disputes involving illegal termination of contracts. When a judge says that “the right to subsistence and health is the most basic human right enjoyed by citizens, is protected by law, and may not be illegally violated by any organization or individual,”31 it means that the right to subsistence and health, as the most basic human rights, are a bottom-line issue and enjoy inviolability. In a labor rights dispute, after finding that the employer had illegally terminated the labor contract, the judge also argued: “It should be emphasized that the right to work is the basis of the right to subsistence, and the right to subsistence is a core human right... The illegal termination of the labor contract violates the labor rights of the pregnant female worker.”32 In general, judges are more cautious and restrained in citing “human rights” as the reasons for their judgments, the concept of human rights in civil judicial documents is mostly associated with those rights and interests that are most inviolable.

C. The protection of human rights aims to achieve equal rights

Both international human rights norms and human rights doctrine recognize equality as a core human right. But it should also be noted that the popular view of equality is plural.33 When the judge invokes “equality” in an argument, he must take into account the acceptability of equality as a human rights reason in individual cases. In civil judicial documents, human rights and equality are both cited, most commonly in traffic accident liability disputes. Although the image of equality in these cases is three-dimensional and multi-faceted, its meaning is clear and focused, and it mainly has two dimensions: First, equal treatment is given based on equality of human dignity; second, differential treatment is given based on the fact that people are not equal in status and ability, that is, the weak are given preferential care.

As far as equality in the first meaning is concerned, the typical example of civil judicial documents is a response to “equal life but a different price.” For a considerable period of time, the amount of compensation paid for those who died in the same traffic accident was quite different due to the difference in urban and rural hukou (household registration), thus violating the human rights principle of “equality before the law.” On April 27, 2022, the Supreme People’s Court issued A Decision on Amending the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Personal Injury Compensation Cases, equalizing the compensation standards for urban and rural residents. However, before that, many local courts had promoted an “equal price for life” in judicial trials. In many similar cases, some courts not only adopted a uniform standard of compensation between urban and rural residents, but also made special explanations in their judgments, emphasizing that “calculating death (disability) compensation according to the same standard in the same traffic accident is an expression of respect for human rights and reverence for life,”34 or that “the principle of higher death compensation is adopted, and the calculation according to the standard of urban residents is an expression of respect for human rights and a good embodiment of equal rights”.35

In terms of equality in the second meaning, typically, civil judicial adjudication tends to protect the vulnerable party in traffic accidents. In modern society, every individual faces multiple risks, but different individuals have great differences in risk control and tolerance. Fair laws must treat the weak well.36 In the field of road traffic cases, the law generally finds that the party driving a motor vehicle is in an advantageous position and is better able to control risks. The judge finds that “the party who uses the higher speed vehicle should bear a higher duty of care for the resulting danger,” reflecting “respect for basic human rights and the protection of vulnerable groups in road traffic operations.”37 Here, human rights and the protection of vulnerable groups for substantive equality become the most acceptable grounds for the distribution of rights and obligations. Of course, taking a traffic accident liability dispute as an example, the judge has a more explicit explanation for the intrinsic relationship between the two: “The economic compensation function of mandatory liability insurance for traffic accidents guarantee that victims of motor vehicle accidents can be compensated in a timely and reasonable manner, help protect the legitimate rights of victims of motor vehicle road traffic accidents, protect the interests of more vulnerable groups as much as possible, and embody the spirit of people-oriented, caring for life and respecting human rights.”38 The simple idea of protecting the weak represents the spirit of human rights, which not only conveys a view of judicial human rights but also implies a practical technique of human rights: The expression and implication of an effective concept of human rights in the administration of justice must not be abstract. In other words, the validity of the concept of human rights does not lie in grand abstract theories or professional and profound reasoning, but in simple truths that the general public can accept and have become accustomed to.

IV. The Function of “Human Rights” in Civil Judicature

Human rights are an intrinsic value of justice, and scholars have even suggested that: “Human rights are the highest form of judicial value and are the fundamental starting point and ultimate goal of all judicial activities.”39 Regardless of the actual situation, it is undeniable that human rights have an extremely important discourse power in judicial practice. This discourse power, as mentioned above, also reflects the concept generally recognized and accepted by society, and is therefore bound to become a “judicial reason” used in judicial decisions. The term “human rights” has indeed played a complementary and practical function in civil judicial adjudication.

A. Declaration of value

Justice is the application of legal rules. However, such an application is not a purely technical activity that is mechanical, passive, and value-free but is deeply rooted in or committed to the realization of legal values. Value as a premise or purpose not only underlies the judge’s judicial thinking process but sometimes directly appears in the argument of the judicial document, playing the role of value declaration. In some cases, the use of the concept of human rights in civil judicial documents is not related to the analysis of legal issues or the interpretation of legal rules but is only intended to emphasize a legal value that cannot be questioned and needs to be taken seriously. In a dispute over the confirmation of land contract and operation rights, the plaintiff claimed that the defendant’s house building affected the plaintiff’s cultivation and harvest. From the perspective of legal provisions, the general provisions on land contract and operation rights and adjacent right clauses in the Property Law of the People’s Republic of China are sufficient for adjudication,40 and there is no need for “human rights” to provide additional arguments, or in other words, “the protection of human rights is not an indispensable reason.” The court did cite the relevant provisions as the basis for its decision, but still directly stated in the first sentence of the argument section: “This Court believes that food is the foundation of livelihood and the cultivation of land by farmers is the most basic human right.”41 This is common in civil judicial documents. For example, in the aforementioned case, the judge argued that “the right to life is the supreme basic human right, and no one can illegally deprive others of their right to life, and citizens themselves should cherish it” and “this Court believes that the right to subsistence and health is the most basic human right enjoyed by citizens, is protected by law, and may not be illegally violated by any organization or individual.” In all these statements, “human rights” as a reason are not indispensable, but mainly interpret, emphasize and advocate the legal value contained in the disputed issues. In a traffic accident liability dispute, the value the court judgment advocated is particularly obvious: “When a motor vehicle accident occurs, human life and health should be given top priority, victims should be sent to hospital promptly. This Court advocates a positive and healthy social custom of cherishing life and respecting human rights.”42

In a sense, the function of value declaration and practice of “human rights” in civil judicial documents are the result of the integration of society, law, and politics. In recent years, the concept of human rights has been further desensitized. “Respect for and protection of human rights” are no longer just legal values, but have developed into a particularly important political discourse instead, which can often provide additional persuasion for legal reasoning. At the same time, these judicial cases in which the value is declared will further shape (or at least profoundly affect) the public’s perception and understanding and even internalize the respect for and protection of a human right as a premise that can be fully accepted without thinking, thereby consolidating and strengthening the legitimacy of human rights values.

B. Strengthened argument

“Legal norms themselves are abstract, ambiguous and fluid, and the judges must have sufficient discretion,” but “the arbitrary appearance of the judge’s discretion determines that almost any judgment might be rejected, so the judicial document must explain to the audience why this result was chosen over other results.”43 In some cases, although the judges can obtain definitive decisions by applying specific rules of law, they still choose “human rights” to make their decisions more persuasive.

In summary, judicial documents are strengthened through the use of human rights mainly in three forms. (1) It explains the purpose of the law or the purpose of the legal system, as in the sentence “The legislative purpose of Article 17 of the Tort Liability Law of the People’s Republic of China is to demonstrate the equal protection of human rights and the basic principle of equality before the law”.44 Such an argument usually does not involve “subsumtion,” and does not need shuttling back and forth between legal norms and the facts of the case. Rather, its main function is external perception so that the reason does not “look” weak, to a certain extent. Its strengthening effect is mainly formal, not substantive. (2) It justifies discretion. Such arguments are commonly used in the adjudication of traffic accident disputes. In one of the aforementioned judgments, the court’s argument was a typical one. In this case, the court attempted to resolve the issue of the motor vehicle party bearing more (60 percent) of the civil liability in excess of the compulsory insurance when the motor vehicle and the non-motor vehicle had the same liability in the accident. In the argument part, the court first clarified the legal basis, that is, Article 76 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Road Traffic Safety stipulates that “if there is evidence which proves that a driver of the non-motor vehicle or a pedestrian violates the laws and regulations on road traffic safety and the driver of the motor vehicle has taken the necessary measures to cope with the situation, the liability to be borne by the motor vehicle driver shall be lightened...” The court went on to cite “respect for basic human rights and the protection of vulnerable groups in road traffic” in its argument that “the party who uses the higher speed vehicle should bear a higher duty of care for the resulting danger,” so as to justify and rationalize its “discretionary determination” to impose a higher civil liability on the driver of the motor vehicle. (3) It assists in the demonstration of the validity of civil acts. In a dispute over the distribution of compensation fees for the expropriation of contracted land, the court ruled that the “distribution plan for land expropriation land payment” approved by the villagers’ group meeting was invalid. In the argument, the court first explained the importance of membership rights as basic civil rights by citing the nature of human rights, that is, “the membership rights included in the membership of collective economic organizations are a basic civil right of farmers, which is related to the protection of survival interests and basic human rights.”45 Then the court associated the general exclusion of basic civil rights with the principle of “public order and good custom” in civil law that is, “the general exclusion, by signing a letter of commitment or agreement, of the basic civil right that members of a collective economic organization should enjoy is a violation of “public order and good custom.”46 At this point, it is sufficient to conclude that the “distribution plan for land expropriation land payment” is invalid.

C. Constitutional interpretation

In a considerable number of judicial documents, human rights appear as a constitutional provision that “the state respects and protects human rights,” which is a constitutional interpretation. Constitutional interpretation usually means that when the court interprets the law, it chooses the interpretation scheme that best conforms to the constitutional principles. In a dispute over the exclusion of nuisance, “human rights” were used to interpret a clause of the Land Administration Law that states that “for villagers, one household shall only have one house site.” The plaintiff intended to take back her former daughter-in-law’s house on the grounds of advanced age and lack of means of subsistence. The owner of the house site certificate in the land plot where the disputed house was located was indeed the plaintiff. As far as the legal relationship was concerned, there was no obvious legal dispute in the case. However, the plaintiff, the plaintiff’s eldest son, the family of the former daughter-in-law, and the family of the plaintiff’s second eldest son conducted complex “changes of houses,” and it would be unfair to simply confirm the legal relationship while ignoring the complex reality. In the end, the court did not support the plaintiff’s claim. Instead, it interpreted housing as the most basic right of citizens. The court believed that housing must be guaranteed based on the provision of the Constitution that “the state respects and protects human rights,” that is, “the legitimate rights and interests of citizens are protected by law. Paragraph 3 of Article 33 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China stipulates: “The State respects and protects human rights. Housing as a place for citizens to live is one of the most important carriers of citizens’ most basic rights.” Then, from the perspective of constitutional interpretation, the court explained that the legislative purpose and function of that provision (for villagers, one household shall only have one house site) in the Land Administration Law is to protect the right to housing. The court found: “The plaintiff and his spouse now have housing to live in, and their housing rights and interests have been guaranteed.”47 From the logic of the argument, the court did not use the human rights provision of the Constitution as the basis for adjudication, but as the basis for reasoning, explaining the connotation and extension of the clause based on the understanding of the Constitution. In a dispute involving the rights and interests of members of a collective economic organization, the “married woman” was denied membership in the collective economic organization because of her status as a married woman, and thus could not receive compensation. The focus of the dispute was the boundary of the autonomy of rural collective economic organizations, that is, how to interpret the Organic Law of the Villagers Committees of the People’s Republic of China, which stipulates that “No villagers charter of self-government, rules and regulations for the village, villagers pledges or matters decided through discussion by a villagers assembly or by representatives of villagers may contravene the Constitution, laws, regulations, or State policies, or contain such contents as infringing upon villagers’ rights of the person, their democratic rights or lawful property rights..” The court defined the rights and interests of members and property rights involved in this case as the right to subsistence related to basic material security and thus associated specific civil rights with the human rights provision of the Constitution with the help of the right to subsistence as a human right. It then constructed a constitutional interpretation: “The Constitution states that ‘the State respects and protects human rights’ and the right to subsistence is a fundamental human right... Although the law grants villagers the right to autonomy, this right is limited by boundaries, and members of collective economic organizations may not be deprived of using land as a basic material guarantee for survival.”48

The judicial practice of such cases shows that although people’s courts do not have the right to engage in “authoritative constitutional interpretation” at the level of constitutional review under the current institutional framework, “practical constitutional interpretation” is needed judicially and practically. The projection of the requirements of the Constitution into departmental laws not only helps to unify the legal system, but also allows the Constitution to develop in practice,49 and the concept of human rights can be integrated into specific laws in this process and truly implemented. However, when the court tries to meet this judicial need by taking spontaneous and active measures, it might become arbitrary and imprecise to a certain extent. For example, in the above-mentioned dispute over the exclusion of nuisance, the text of the judgment cites the human rights clause, which should have been used as the “basis for reasoning,” as the “basis for adjudication” and appears in the form of Paragraph 3 of Article 33 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. This unnecessary invocation make the application of the Constitution appear premature in individual cases and also reflects the immature side of constitutional interpretation in practice.

D. Interpretation of fuzzy rules and the ranking of rights

In civil judicature, human rights are also incorporated into judicial reasons in the form of universally accepted human rights principles to clarify the proper meaning of legal provisions with unclear meanings. More specifically, human rights are used to interpret ambiguous rules in a way that deals with the ordering of rights, or rather, the ambiguous rules that human rights principles attempt to explain are usually concerned with the ordering of rights. For example, Article 311 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China: “Where an outsider or the applicant requesting for execution lodges a lawsuit to object to execution, the outsider shall assume the responsibility of presenting the evidence to prove that he/she enjoys the civil rights and interests in the execution subject which are sufficient to exclude compulsory execution.” However, the law and judicial interpretations do not specify what constitutes “the civil rights and interests in the execution subject which are sufficient to exclude compulsory execution.” In a lawsuit against the enforcement of an objection by an outsider, the outsider demanded the freezing and deduction of 550,000 yuan in unpaid wages in the bank account of a construction company be cancelled. The money was the wages of migrant workers applied for by the construction company from the township people’s government for special project funds for immigration. As to whether 550,000 yuan was a “civil interest sufficient to preclude enforcement,” the court first made a special determination on its nature: “Money is generally regarded as a special type of thing, i.e. possession is ownership. However, the money in this case has been clearly defined as the wages of migrant workers including Huang Yongquan, and should be regarded as a particular thing.” After being clearly defined as a particular thing, the key to the judgment is whether the plaintiff has a priority right to compensation. Through an explanation of human rights principles, the judge finally determined the priority of compensation for migrant workers’ wages: “For migrant workers, their wages play a

role of survival guarantee. The judge believes that labor compensation is not an ordinary civil right, but a right related to basic human rights and an absolute right; and that it takes precedence over other rights. The wages of migrant workers are an important factor in social stability and the workers depend on the wages for their basic survival. If compensation is not given priority, the right to the subsistence of the workers will be undermined.”50 It was through the analysis of priority compensation that the judge completed the interpretation of “civil interest sufficient to preclude enforcement”.

Interpreting rules according to human rights principles can be regarded as the judicial application of jurisprudence or legal doctrine. “When legal norms cannot be directly applied simply and inclusively but must be further concretized, by introducing elements other than rich legal provisions through jurisprudence, [the court] interprets the overall meaning of the legal provisions, and subsumes legal norms more smoothly into the facts of specific cases”.51 According to the Guiding Opinions of the Supreme People’s Court on Strengthening and Standardizing the Interpretation and Reasoning of Adjudicative Instruments, the interpretation and reasoning of judicial documents should “explain the jurisprudence”, and “jurisprudence and popular academic views” can be used as judicial reasons, “to improve the legitimacy and acceptability of adjudicative conclusions.” Of course, the human rights principles as jurisprudence in the practice of civil judicial adjudication are usually more consensual than general jurisprudence or legal doctrines. Especially, the principle that “the right to subsistence takes precedence” is a derivative of the human rights concept that “the right to subsistence and the right to development are the primary basic human rights,” which is not only a theoretical consensus but also a position of the state. However, it is also worth

noting that although the principle of human rights in civil judicial adjudication has a stronger consensus, it remains controversial in dealing with the ranking of the rights. For example, when it comes to selecting wage claims or mortgage rights of bankrupt enterprises as the priority rights, some courts hold that “when there is a competition between wage claims and mortgage rights, if the wage is not given priority to the mortgage, it is not enough to protect the defendant’s right to subsistence, since the wage, in this case, is the consideration for the defendant’s labor and the defendant’s sole source of income. The right to subsistence is a human right, which is higher than creditors’ rights.”52 However, many courts have made decisions to the contrary.53 Although the human rights principle of giving priority to the right to subsistence is universal, it remains controversial whether it meets the applicable conditions as judicial reasons and whether it is sufficient to produce the interpretive power for individual cases. Moreover, even the connotation and extension of the right to subsistence itself remains controversial. From this point of view, the human rights principle only provides a possible interpretive reason, which may sometimes make an adjudication result seemingly more acceptable. However, this does not put an end to the legal dispute, and the hasty and generic use of the concept of human rights will lead to judicial uncertainty.

Conclusion

Human rights are not abstract, mysterious, or static, but open, practical, and “living.” They have entered China’s civil judicature in a way that goes against traditional theoretical understanding. In the sample 3,412 civil judicial documents, the use of the term “human rights” is popular among the basic-level courts, covering disputes of various types of causes of action and judicial practice in the 31 provincial-level administrative regions across the country. The concept of human rights has penetrated the positive law system and into the daily life of the public and is becoming an important discourse for evaluating the legitimacy of behavior in social life. The use of the term “human rights” in judicial documents also clearly reflects China’s understanding of human rights. First, the human rights concept that “the rights to subsistence and development are the basic human rights of paramount importance” is now deeply involved in civil judicature and has become an important part of the concept of fairness and justice for judges and parties to disputes. Second, the judicial protection of human rights is usually understood as a bottom-line guarantee; human rights violations mean breaking this bottom-line; and protection of human rights often means upholding those rights and interests that are most fundamental. Finally, the protection of human rights also aims to achieve equal rights. It emphasizes that equal treatment should be given based on equal human dignity and preferential consideration must be given to the weak because of de facto inequality in the status and ability of human beings. Human rights as a concept are not only reflected in judicial documents but also play multiple practical roles in civil judicial adjudication as an important value and reason. First, the use of the term “human rights” has a function of value declaration, which reflects the integration and interaction of society, law, and politics. Second, the introduction of “human rights” helps interpret the purpose of the law or the legal system, provides a legitimate basis for “discretionary” adjudication, assists in the determination of the validity of civil acts, and can play a role in strengthening arguments. Third, in some cases, “human rights” appear as provisions of constitutional human rights, which is, in fact, a “practical constitutional interpretation.” Fourth, human rights are also used as judicial reasons in the form of human rights principles; and are used to interpret ambiguous rules and rank the order of rights in individual cases. Of course, it is also worth noting that although the courts are generally prudent in the use of human rights concepts, norms, and principles in civil judicial documents, the practice remains limited and immature in some cases. Especially, the inappropriate invocation of the Constitution’s human rights provisions is not only redundant but also premature. The broad and imprecise use of concepts such as human rights and the right to subsistence also brings judicial uncertainty.

This paper is only a preliminary attempt to examine the concept of human rights in judicature and the practical function of human rights in judicature. This preliminary attempt is more descriptive and interpretive than constructive. It is intended to show that the picture of human rights discourse in judicature is also worth examining alongside the familiar judicial practice of human rights. Civil judicial documents can be regarded as a lens: Through it, we see that the discourse of human rights has become part of the daily life of the public, serving as an important yardstick for the public’s understanding and evaluation of behavior. Civil judicature can also be understood as a special bond: The public human rights concepts, discourses academic concepts, and principles of human rights, together with the official positions and norms of human rights, interact with each other in civil judicature and influence each other.

* ZHENG Ruohan ( 郑若瀚 ), Lecturer, Human Rights Institute, Southwest University of Political Science and Law. Doctor of Laws.

1. Liu Lianjun, “Innate Human Rights as Political Rhetoric,” Nanjing Normal University (Social Science Edition) 5 (2020): 122-123.

2. Liu Zhiqiang, “On the Three Jurisprudence of Human Rights Law,” Law and Social Development 6 (2019): 59-60.

3. Zhang Xiang, “On the Defensive Function of Fundamental Rights,” The Jurist 2 (2005): 66-67.

4. Joseph Raz, “Human Rights Without Foundations,” Peking University Law Journal 3 (2010): 373-374.

5. Fu Junwei, “Directions for Modern EU Private Law: Human Rights Protection and Social Justice,” Journal of the Party School of the

CPC Central Committee 6 (2009): 74.

6. Liu Zhengfeng, “From the ‘Anti-Discrimination Principle’ to the Civil Transaction Relationship and Observing the Innovation of Contemporary Civil Law Concepts,” Law and Social Development 1 (2017): 60-61.

7. Qiu Jing, “On the Application of the Principle of Proportionality in Private Law Relationships: Taking British and European Court of Human Rights Cases as a Perspective,” Contemporary Law Review 1 (2016): 113-115.

8. Andrew Clapham, Human Rights Obligations of Non-State Actors, translated by Chen Huiping (Beijing: Law Press · China, 2013), 43.

9. On PKULaw.com, the system counts all situations in which “person” and “right” are used in conjunction in the search results, which included a large number of intrusive search results such as “creditor’s rights,” “parties’ rights” and “debtor’s rights.”

10. White paper entitled China’s Human Rights Situation, on the website of the Information Office of the State Council, accessed July 4, 2022.

11. (2019) Yu No. 1081, Min Chu No. 5790 Civil Judgment; (2019) Xiang No. 0203, Min Chu No. 3642 Civil Judgment; (2017) Xiang No. 0203, Min Chu No. 3413 Civil Judgment; (2016) Xiang No. 0203 Min Chu No.

2221 Civil Judgment, etc.

12. (2016) E No. 01 Zhi Yi, No. 321 Civil Judgment.

13. (2019) Gui No. 14, Min No. 1 Civil Judgment.

14. (2017) Chuan No. 06, Min Zhong No. 287 Civil Judgment.

15. Yu No. 0110, Min Chu No. 9581 Civil Judgment.

16. Liu Zhiqiang, “On the Three Jurisprudence of Human Rights Law,” Law and Social Development 6 (2019): 53.”

17. (2014) Nan Min Yi Chu Zi No. 1310 Civil Judgment.

18. (2015) Jin Min Chu Zi No. 2201 Civil Judgment.

19. (2016) Ji No. 0194 Min Chu No. 13 Civil Judgment.

20. (2015) Ning Min Chu Zi No. 1319 Civil Judgment.

21. White Paper entitled China’s Human Rights Situation, on the website of the Information Office of the State Council, accessed January 4, 2022.

22. Of course, in the (2015) Xiang Gao Fa Min Yi Zhong Zi No. 421 Civil Judgment can be seen the expression that “citizens’ right to

subsistence and development is a basic human right and the basic prerequisite for the realization of other human rights.”

23. (2011) Cong Min Chu Zi No. 428 Civil Judgment.

24. (2019) Xiang No. 0203 Chu No. 2932 Civil Judgment; (2019) No. 1081 Min Chu No. 5790 Civil Judgment;

25. (2015) Heng Min Yi Zhong Zi No. 753 Civil Judgment.

26. (2019) Gan No. 11 Min Zhong No. 1047 Civil Judgment.

27. (2020) Lu No. 0103 Min Chu No. 4630 Civil Judgment.

28. (2019) Lu No. 14 Min Zhong No. 1840 Civil Judgment.

29. (2019) Hei No. 01 Min Zhong No. 5173 Civil Judgment.

30. Ren Shuaijun and Xiao Wei, “On the Double Meaning of the Realization of Human Rights Values,” Journal of Central South University (Social Science Edition) 4 (2016): 116.

31. (2018) Gan No. 0822 Min Chu No. 13 Civil Judgment. Similar expressions can be found in the (2018) Zhe No. 4 Min Zhong No. 2105 Civil Judgment.

32. (2018) Jing No. 03 Min Zhong No. 8725 Civil Judgment.

33. Zhang Yonghe, “A Review of the Concept of Equality Among the Chinese Public,” China Legal Science 4 (2015): 121.

34. (2019) Jing No. 0112 Min Chu No. 39040 Civil Judgment; (2017) Jing No. 0114 Min Chu No. 11056 Civil Judgment.

35. (2018) Yu No. 02 Min No. 3969 Civil Judgment.

36. Hu Yuhong, “How the Law Faces the Weak,” Political and Legal Review 1 (2021): 29-30.

37. (2019) Lu No. 1725 Min Chu No. 1303 Civil Judgment; (2015) Qian Nan Min Zhong Zi No. 513 Civil Judgment.

38. (2018) Lu No. 0685 Min Chu No. 2839 Civil Judgment.

39. Wang Xigen and Guo Min, “On the Judicial Discourse System of Human Rights with Chinese Characteristics,” Huxiang Forum 6

(2017): 133.

40. Article 125 of the Property Law of the People’s Republic of China: “Contractors for the right to land management shall, in accordance with law, have the right to possess, use, and benefit from the cultivated land, forestlands, grasslands, etc. which are under their contractual management, and shall have the right to engage in agricultural production, including crop cultivation, forestry and animal husbandry.” Article 84 of the Property Law of the People’s Republic of China: “owners of neighboring immovables shall properly deal with their neighboring relations in adherence to the principles of conduciveness to production, convenience for daily lives, unity and mutual help, and fairness and rationality.” Article 87: “Where a neighboring obligee has to use for passage, etc. the land of an obligee of immovables, the latter shall provide the necessary convenience to the former.”

41. (2019) Yun No. 0381 Min Chu No. 2935 Civil Judgment.

42. (2019) Hei No. 0124 Min Chu No. 1524 Civil Judgment.

43. Jin Fengliang, “The Basic Principles and Rule Construction of the Doctrine Cited in Judgment Documents,” Chinese Journal of Law 1

(2020): 193-194.

44. (2015) Shang Min Zhong Zi No. 1313 Civil Judgment.

45. (2019) Xiang No. 07 Min Zhong No. 160 Civil Judgment.

46. (2019) Xiang No. 07 Min No. 160 Civil Judgment.

47. (2015) Zao Cheng Min Yi Chu Zi No. 345 Civil Judgment

48. (2019) Yu No. 1081 Min Chu No. 5790 Civil Judgment.

49. Feng Jianpeng, “Constitutional Citation and Its Function in China’s Judicial Decisions: An Empirical Study Based on Published

Judgment Documents,” Chinese Journal of Law 3 (2017): 53.

50. (2019) Chuan No. 15 Min Chu No. 29 Civil Judgment.

51. Guo Dong, “The Meaning, Structure and Function of Jurisprudence Concepts: An Analysis Based on 120,108 Judicial Documents,” China Legal Science 5 (2021): 195.

52. (2016) Ji No.01 Min Zhong No. 9125 and other civil judgments. In addition, it is worth noting that the court’s idea that “human rights are higher than creditors’ rights” should clearly refer to debts involving human rights are superior to debts in general, since wage debts are themselves debts. This reflects the sometimes-arbitrary use of the concept of human rights by courts.

53. (2020) Chuan No. 10 Min Zhong No. 368 Civil Judgment; (2020) Lu 06 Min Zhong No. 3480 Civil Judgment.

(Translated by CHANG Guohua)