Procedural Transition in the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in the Eyes of the European Court of Human Rights

HE Wanyu*

Abstract: The principle of the best interests of the child, as a criterion for substantive review, is conceptually ambiguous and uncertain in its application. To mitigate this dilemma in the application of the principle of the best interests of the child, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has made a procedural transition in the interpretation and application of this principle, shifting from conducting specific proportionality analysis or interests balancing in cases related to children to examining whether States Parties have applied the principle of the best interests of the child in their judicial procedures. Moreover, ECHR has developed three procedural review schemes: holistic reviews, key factors-based reviews and factor list-based reviews.Compared with substantive reviews, procedural reviews adhere to the ECHR doctrine of margin of appreciation, restrict the free discretion of the court, give play to the effect of procedural autonomy, and pursue the value of subjective procedural justice, which has its own unique theoretical value and practical significance, and provides a feasible reference for China to interpret and apply the principle of the best interests of the child.

Keywords: the principle of the best interests of the child · semi-procedural review · the doctrine of margin of appreciation · the theory of procedural justice

I. Problem Statement

Since the Enlightenment, children have gradually changed from objects of rights to subjects of rights, with their legal rights and interests gradually recognized, and their legal status continuously improved. However, children cannot be equal to adults in terms of intellectual capacity and physical strength, so they need special care and protection by law. Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted in 1989, clarifies the principle of “the best interests of the child,” stating that in all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration. The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) regards “the best interests of the child” as one of the four fundamental principles for the interpretation and implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1 and underlines that it is a threefold concept: 1. A substantive right; 2. A fundamental, interpretative legal principle; 3. A rule of procedure.2 With the wide recognition of the concept of children as subjects of rights in the international community, the principle of the best interests of the child has gradually become a legal obligation and moral norm for the protection of children’s rights at the regional and national levels. As one of the earliest States Parties to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, China has actively fulfilled its obligations under the Convention and has formulated a number of laws, regulations and policy documents to implement the principle of the best interests of the child3 while truly respecting and safeguarding the principle in judicial judgments.4 In the process of interpreting or applying the principle of the best interests of the child, theoretical researchers and judicial practitioners both in China and abroad consider this principle a criterion for substantive review. As for cases concerning children, an approach of interests balancing shall be adopted to review specific facts and take into full consideration the proportionality between the purposes and means for the protection of children.5 The most prominent problem for the principle of the best interests of the child, as a criterion for substantive review, lies in its conceptual ambiguity and the uncertainty in its application. Although scholars have made various types of attempts,6 it is obviously difficult to reach a consensus in different types of specific cases, and there are many extralegal interference factors.7 Meanwhile, the CRC requires to evaluate and determine the connotation of the principle of the best interests of the child in individual cases according to the specific situations of the children involved.8 Such a dynamic interpretation is the lifeline for the continuous development of the principle of the best interests of the child, but it also brings grave challenges to how to interpret and apply this principle in practice. That is to say, in specific cases involving the review of the principle of the best interests of the child, the judges have relatively greater discretionary power. This inevitably presents higher requirements for relevant judges and increases the involved parties’ doubts about judicial predictability.

As a regional human rights court, the ECHR also faces a dilemma in the interpretation and application of the principle of the best interests of the child. The European Convention on Human Rights lacks direct stipulations on the rights of children. However, the principle of the best interests of the child remains the most important criterion for the ECHR to adjudge cases related to children. This is because: First, all States Parties to the European Convention on Human Rights have joined the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In accordance with Article 53 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the criteria for human rights protection of the States Parties shall not be inferior to the requirements of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; 9 Second, Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights, namely “prohibition of discrimination,” stipulates that the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground including age, providing the normative basis for the protection of children with special laws and the application of the principle of the best interests of the child; Third, the principle of the best interests of the child has strong global influence and widespread applicability and offers the necessary value consensus for the ECHR to handle cases related to children. To address the aforesaid dilemma, the ECHR has undergone a procedural transition in the interpretation and application of the principle of the best interests of the child, shifting the focus from substantive review to procedural review, blazing a new path for interpreting and applying this principle.10 In this context, with the cases of the ECHR as the center and the boundary between substantive review and procedural review as the key clue, this paper tries to explore the specific connotations, theoretical basis and practical significance of the procedural transition of the principle of the best interests of the child, so as to examine whether this principle can realize a balance between the flexibility of its interpretation and the certainty of its application under such a procedural transition.

II. Connotations of the Procedural Transition of the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child: The Boundary Between Substantive Review and Procedural Review

A. The logic for substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child

In the ECHR, personal appeals related to children mainly quote Article 2 (“right to life”), Article 3 (“prohibition of torture”), Article 8 (“right to respect for private and family life”), Article 9 (“freedom of thought, conscience and religion”), and Article 14 (“prohibition of discrimination”).11 Such rights have fixed review procedures in the ECHR. Take Article 8 (“right to respect for private and family life”) as an example: First, reviewing whether the appeal is under the jurisdiction of Article 8, namely whether it belongs to the right to respect for private and family life; Second, reviewing whether there is violation of Section 1 of Article 8, namely whether it interferes with the excise of the right to respect for private and family life; Finally, reviewing whether such interference meets the reasonable limits of Section 2 of Article 8. There are three criteria, namely “in accordance with law,” “legitimate aim” and “necessary in democratic society.”12 These review procedures are in conformity with the thinking framework of constitutional jurisprudence on the limitations of basic rights,13 and represent a typical substantive review of human rights. The principle of the best interests of the child often appears in the third procedure as a significant criterion to judge whether the interference of the government with the excise of this right is in accordance with the law, has a legitimate aim, or is necessary in a democratic society. In the handling of a series of cases related to children, the ECHR has always adopted the approach of substantive review, such as the 2004 case of Sabou and Pircalab v. Romania14 that involved custody disputes, the 2006 case of Üner v. the Netherlands15 that involved deportation, the 2008 case of Carlson v. Switzerland16 and the 2020 case of Andersena v. Latvia17 that involved international child abduction.

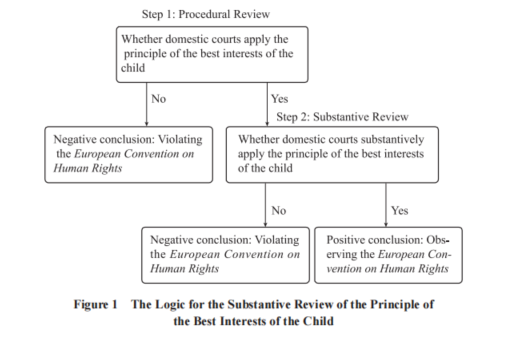

To be specific, the logical sequence for substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child is from “procedural to substantive”: In the dimension of procedural review, namely the first step, the ECHR confirms whether domestic courts of various countries apply the principle of the best interests of the child, and if not, the ECHR will give a “negative” conclusion, namely the relevant domestic courts fail to duly observe their obligations as stipulated in the European Convention on Human Rights; If this principle is applied, the ECHR cannot directly give a “confirmative” conclusion but enter the stage of substantive review, namely the second step — employing approaches such as the principle of proportionality and the balance of interests to review whether those domestic courts meet the requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights in respecting and safeguarding the principle of the best interests of the child.18 The logic for the substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child is shown in Figure 1 below. How does the ECHR review whether those domestic courts substantively apply the principle of the best interests of the child in the second step? In addition to the holistic use of such approaches as the principle of proportionality and the balance of interests,19 it must determine the specific rules for the application of the principle of the best interests of the child as per the principle of reviewing case by case.20 The disadvantages of substantive review lie in its conceptual ambiguity and the uncertainty in its application, making it hard to form a unified standard for the application in different types of specific cases. Just as some scholars criticize, “the innate uncertainty of the principle of the best interests of the child results in the judges getting lost in the dilemma between individual justice and free discretion.”21 It is noteworthy that in the course of substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child, the first step is an approach of procedural review, plays the role of a tool for procedural review, and completely serves the substantive review. In other words, the procedural review isn’t indispensable to the substantive review, and the logic focus of the substantive review lies in the second step.

B. The logic for procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child

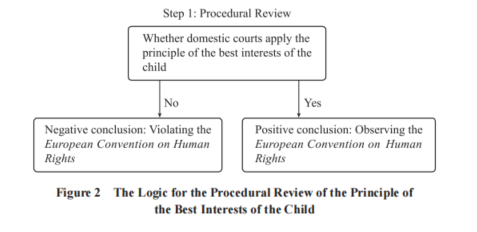

The procedural review of the ECHR originated from the review of procedural rights listed in the European Convention on Human Rights. For instance, according to Article 6 (“right to a fair trial”) of the European Convention on Human Rights, everyone charged with a criminal offense has procedural rights such as the right to defend himself through legal assistance of his own choosing and the right to have the free assistance of an interpreter if he cannot understand or speak the language used in court. The procedural review of those procedural rights is enough to ensure a fair trial.22 As the ECHR pays greater and greater attention to the neutrality of judgments, under the impact of the doctrine of margin of appreciation, procedural review demonstrates a trend extending from procedural rights to substantive rights.23 Scholars have coined different definitions for such new types of procedural review, such as “process-oriented proportionality review,”24 “structural due process,”25 “semi-procedural review,”26 and “responsible domestic courts doctrine.”27 Whatever the terminologies or definitions are, those interpretations all divide procedural review and substantive review: In substantive review, the ECHR uses an approach of balanced interests to normatively review the results of judgments of domestic courts, while in procedural reviews, the ECHR focuses on reviewing the process and methods of domestic courts to make judgments. Specifically, the basic logic for the procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is that: in the first step, the ECHR confirms whether the principle of the best interests of the child has been applied by domestic courts, and if not, the ECHR will make a negative conclusion that the domestic courts have not properly respected the obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights; If yes, the ECHR can directly conclude that domestic courts have complied with the relevant provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, without the need to enter the stage of substantive review, i.e. bypassing the second step of substantive review. The logic for the procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is shown in Figure 2.

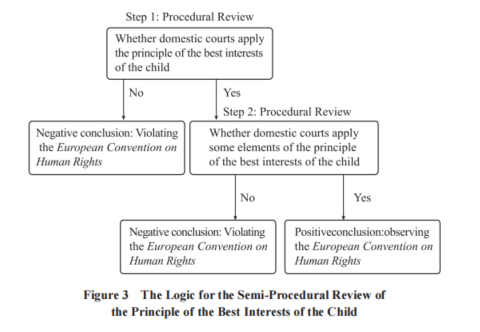

The above-mentioned basic approach to the procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is also called “purely procedural review.”28 That is to say, a mere procedural review of whether the principle of the best interests of the child has been applied by domestic courts can lead to a positive or negative conclusion. As a matter of fact, however, procedural review on the principle of the best interests of the child cannot absolutely get rid of the impact of substantive factors. Therefore, in terms of procedural review, the ECHR has further refined the requirements for the quality of the application of the principle of the best interests of the child in the procedures of domestic courts, which must employ certain key factors pertaining to the best interests of the child or conduct a review of the list of factors. In contrast with “purely procedural review,” this approach is called “semi-procedural review” by scholars.29 This complies with the interpretation made by the CRC on the best interests of the child as a procedural right: First, all decisions related to children must conduct an evaluation of their impact on the best interests of the child procedurally; Second, the reasons for all decisions must take into consideration the best interests of the child30 In terms of review logic, in the first step, the ECHR conducts a simple procedural review. However, it cannot directly reach a positive conclusion on whether domestic courts properly apply the principle of the best interests of the child; In the second step, the ECHR employs procedural review instead of substantive review to evaluate whether domestic courts apply some elements of the principle of the best interests of the child, rather than make specific review on how domestic courts use those elements and to which degree they use those elements. The logic for the semi-procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is shown in Figure 3.

In summary, the procedural transition of the principle of the best interests of the child in the ECHR is embodied by the division between substantive review and procedural review: The former focuses on the legitimacy, rationality and proportionality of the application of the principle of the best interests of the child in States Parties, employs the balance of interests or the principle of proportionality as the review method, and determines what are the best interests of the child in specific cases of various types; The latter focuses on the procedural nature of the application of the principle of the best interests of the child in States Parties, and uses a simple deductive reasoning method to examine whether States Parties respect and safeguard the principle of the best interests of the child in procedures. In fact, the ECHR still emphasizes substantive elements of the procedural review methodology, which has led to the emergence of “semi-procedural reviews.” At the same time, a procedural shift in the principle of the best interests of the child is happening: On the one hand, in terms of the number of relevant cases, only a minority of the cases related to children have adopted procedural review, and substantive review remains the main review method used by the ECHR;31 On the other hand, procedural review isn’t completely separated from substantive review, and in cases where procedural review is taken, “purely procedural review” remains rare, and the majority involves “semi-procedural review.” However, compared with substantive reviews, the advantages of procedural reviews are obvious: The logic of procedural reviews can be applied to all types of children-related cases, without having to examine all elements that may affect the interests of the child in each case, leading to the universality and certainty of application. Therefore, procedural reviews can help the ECHR save judicial costs and improve judicial efficiency while increasing the certainty and predictability of the judgments made by the ECHR.

III. The Ternary Criteria for Procedural Review of the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child

With regard to the principle of the best interests of the child that is undergoing a procedural shift, under the logic of the “purely procedural review” and “semi-procedural review,” the ECHR has further developed three review schemes through further typification: Holistic reviews, key factor-based reviews and factor list-based reviews.

A. Holistic reviews

Holistic reviews comply with the logic for procedural reviews of the principle of the best interests of the child as shown in Figure 2, being is a kind of “purely procedural review.” The ECHR can directly reach a positive or negative conclusion by conducting a single-step procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child. The holistic review was first applied in a case involving custody disputes, namely the 1987 case of “W. v. the United Kingdom,”32 and was gradually established in a series of subsequent cases.33 Taking the 2018 case of “Royer v. Hungary”34 that involved international child abduction as an example: The applicant Royer was French who got married to K.B.V. from Hungary in France, and the two gave birth to a son named L. The couple later broke up. Without informing Royer, K.B.V. brought L. back to Hungary. Then, Royer initiated a lawsuit against K.B.V. in a French court. The French court deemed that K.B.V. illegally separated L. from Royer and adjudged that K.B.V. and Royer shall enjoy joint custody, and Royer shall perform guardianship while K.B.V. shall enjoy the visitation right. According to the Brussels Convention II, the French court requested judicial enforcement to Hungary. Upon hearing, a domestic court of Hungary held that as per the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction, L. shall stay with his mother K.B.V., which is in his best interests, and thus refused to acknowledge and enforce the judgment made by the French court. Under desperation, Royer took their son L. from K.B.V. by force and brought him back to France, causing severe physical injuries to K.B.V. The French police arrested Royer upon the warrant issued by the Hungarian court and sent L. back to his mother. Running out of domestic legal relief, the plaintiff Royer later submitted a personal appeal to the ECHR, claiming that the Hungarian side’s refusal to acknowledge and enforce the judgment made by the French court violates the “right to respect for private and family life” that he enjoys according to Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The ECHR concluded that the focus of controversy concerning this case lies in which meets the best interests of L. — staying with his father in France or living with his mother in Hungary. In nature, it is a matter of interest balancing between the father and the mother. The ECHR made argumentation from the perspective of procedural justice instead of substantive obligation and believed that Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights imposes the Hungarian court the procedural obligation to review what is in the best interests of the child. The Hungarian court fulfilled this procedural obligation and rejected the appeal of the plaintiff Royer with a rational judgment, but the French court didn’t duly perform its procedural obligation to review the principle of the best interests of the child35. The ECHR stressed that it respects and trusts the judgment made by the domestic court of Hungary, and under the premise of lacking substantive proof, the judgment of the domestic court shall not be deviated, so the Hungarian court’s judgment didn’t violate Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In this case, the ECHR adopted a holistic review and directly gave a positive conclusion through procedural review in the first step. Some scholars question the rationality of holistic review, arguing that this simple one-step procedural review will weaken the protection of personal rights. They hold that it is no question to reach a negative conclusion through procedural review, but directly reaching a positive conclusion means indulgence for domestic courts and neglect of personal rights.36 The ECHR responded that the “proceduralization” of substantive rights aims to promote the substantive application of the European Convention on Human Rights in relevant countries, and the clarification of obligation content and scope arising from procedural review is to optimize the protection of personal rights.37 Such a holistic review, also known as a “purely procedural review,” is rare in the practice of the ECHR. Despite the controversy concerning its effectiveness in the protection of some rights, holistic reviews are as a basic mode of procedural review lays the practical foundation for the development of the following two types of semi-procedural review. The emergence of the holistic review indicated that the ECHR has incorporated procedural justice and procedural efficiency into its pursuit of juridical value while ensuring substantive fairness and justice.

B. Key factors-based review

The key factors-based review scheme follows the logic of the semi-procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child as shown in Figure 3. Based on the holistic review, it has higher requirements on the quality of procedural review. For procedural review, the key factors are substantive factors. They serve procedural review itself, rather than the method of interest balancing.38 The key factors to be reviewed vary for various types of cases or even different individual cases: For instance, in a case of custody dispute in which biological parents contested custody by the State, the ECHR held that the key factors of procedural review were to hear the biological parents’ opinions;39 In another case related to custody disputes between parents, the key factors lied in the child’s opinions40; In a case of the deportation of the biological father, the key factors of the procedural review lied in whether the deportation met the “ultima ratio principle.”41 Take the 2015 case of M. and M. v. Croatia as an example: The complainants are in a mother-daughter relationship, the parents divorced due to the breakdown of their relationship, the father I. M. was granted custody because of domestic violence by the mother M., and the mother had visitation rights. The daughter M. and the mother M. constantly complained to the authorities about domestic violence against the father, demanding criminal sanctions against the father and a change of custody. Suspecting the possibility of the daughter being manipulated by the mother, the Croatian authorities repeatedly questioned and investigated both parents to determine what best served the daughter’s best interests. The daughter and the mother filed individual complaints with the ECHR on the grounds that the domestic proceedings were too long (lasting four years and had not yet been completed). In the course of reviewing whether the Croatian authorities had violated Article 8 (“Right to respect for private and family life”) of the European Convention on Human Rights, the ECHR affirmed the consideration of the best interests of the child by the Croatian authorities, but that it is equally important to listen to the opinions of the child in accordance with the procedural requirements of the principle of the best interests of the child. The age and maturity of the minor daughter enabled her to express her wishes, and the failure of the Croatian authorities to consider her opinions as an important factor in the judgment during the four-year litigation period violated the principle of the best interests of the child and constituted a violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. 42 In this case, the key factor established by the ECHR was to “listen to the child’s opinions,” which was followed and further developed in subsequent custody dispute cases. Since then, judgments for similar cases have further deepened the review standard of “listening to children’s opinions” as a key factor: It is also not enough for domestic courts to only listen to the opinions of children, but also to take into account the weight of the children’s opinions in all factors of review. Since the importance of children’s opinions increases with their age and mental maturity, the mere hearing of children’s opinions in form without giving them substantive importance also constitutes neglect of the principle of the best interests of the child.43

C. Factor list-based review

Similarly, factor list-based review also follows the logic of semi-procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child as shown in Figure 3. Its difference from key factors-based review lies in that some key factors of review in the second step are expanded to whether juridical precedents constitute a factor list. The factor list-based review scheme is often used in substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child.44 For example, the CRC recommended that the following factors should be taken into account when considering the best interests of the child: the child’s opinions and identity, the preservation of the family environment and relationships, the child’s care, protection and security, and vulnerability, and the child’s right to health and education45. The factor list-based review scheme can help judges quickly grasp the main points of the review, increase the predictability and stability of judgments, and take into account the substantive protection of rights to a certain extent. Take the 2017 case of “M. L. v. Norway”46 as an example: The case was a typical custody dispute. The applicant M. L. has two sons, both of whom have ADHD and require special care. Given that the applicant was unable to support him, the elder son was sentenced to be under the guardianship of the complainant’s mother and stepfather in 2010. The younger son X was born in 2012, and the Child Welfare Service assessed that the complainant’s parents were no longer suitable to serve as guardians of X, who should be placed in a foster home. The applicant appealed to the local City Court for her parents to act as guardians of X, and the City Court set up a collegial panel composed of the court staff, psychologists and social workers, which supported the decision of the Child Welfare Service as being in the best interests of X. The collegial panel proposed using the following factors to evaluate which decision met the best interests of X: The first is the ages of the complainant’s parents. The Child Welfare Service held that the complainant’s parents are old and don’t have enough energy to take good care of the two children, while the applicant insisted that the age itself is not important. The court deemed that the age of the guardians, although not a key issue, is worth considering; The second is the willingness of the complainant’s parents to raise X. and the complainant’s parents are willing to raise X, which is of course in X’s best interests; The third is the degree of cooperation of the complainant’s parents with the Child Welfare Service. The Child Welfare Service said that the complainant’s parents sometimes failed to cooperate in the process of raising the complaint’s elder son, and the court found that the complainant’s parents are generally impeccable, and it is normal for them to have some friction in the process of raising the child for so many years; The fourth is the healthy growth of X. The X’s placement in the family in which his elder brother grows up is conducive to his own growth, and the applicant might still be expected to have as much contact as possible with her younger son X, which is unconducive for X to establish an affectionate attachment to foster parents; The fifth is the healthy growth of the elder son. Considering the old age of the foster parents and the fact that the applicant had renounced motherhood for the elder son, caring for X would inevitably lead to adverse effects on the elder son47. In conclusion, the City Court found that in the present case, the above-mentioned benefits were outweighed by concerns to make the applicant’s parents the guardians of X, and that placing X into a new foster home meets his best interests. The applicant argued that the judgment of the City Court failed to give full consideration to the possibility of immediate relatives serving as the guardians, separating X from his blood brother, and then appealed to the ECHR against Norway for violating Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The ECHR held that the focus of dispute in this case lay in what’s in the best interests of the child, and its judgment also followed the logic of semi-procedural review. The first is whether Norway’s domestic court took into account the principle of the best interests of the child, and the second is whether it carried out a balanced and reasonable assessment of the respective interests of each person as it conducted further procedural review according to the requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights. Given the circumstances of the case, the domestic court fully considered all factors concerning the raising of X and made a balanced and reasonable assessment of the applicant, the applicant’s parent, the elder son, and the younger son X before eventually giving a positive conclusion. The reasons for that decision were sufficient, and the placement of X in an external foster home was in the best interests of the child. Accordingly, there has not been a violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. 48 The difference between factor listbased review and substantive review is that the ECHR is not a substitute for the proportionality analysis or balance of interests of the domestic courts, but rather has full confidence in the professional judgment of the domestic courts on specific matters, and the review of the ECHR is limited to whether the domestic courts exercised their powers reasonably, prudently and in good faith, and whether the reasons and factors advanced by the domestic courts are relevant and sufficient.49

As mentioned above, in terms of the logic of the procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child, the ECHR has developed three procedural review schemes: holistic review, key factors-based review, and factor list-based review. Holistic review is a purely procedural review scheme, with which the ECHR examines whether the States Parties formally respect the principle of the best interests of the child; The key factors-listed review focuses on the substantive factors in the application of the principle of the best interests of the child and whether certain key factors or the factor list are met. As shown by precedent cases, procedural interpretations of the principle of the best interests of the child have a strong vitality and unique advantage in being applied flexibly in different types of cases concerning children, instead of having to establish different standards of interpretation and application in different types of cases and different provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, as substantive reviews require.

IV. The Legitimacy and Value of the Procedural Transition in the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child

Procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is a new “possibility” developed in the judicial practice of the ECHR, which has been questioned since its inception: What is the theoretical basis of procedural review? Will the emphasis on procedural review affect individual fairness and justice and be detrimental to the protection of human rights? Is there a need for a procedural transition in the substantive examination of the cases related to increasingly mature children? The judicial practice of the ECHR cannot provide theoretical justification for the procedural transition. Therefore, it relies on a return to the theoretical basis of the procedural review, that is, the “theory of procedural justice.” At the same time, answering the above questions also means affirming the unique value of procedural review, further promoting procedural review in the best interests of children, and even providing theoretical support for reference and application in China’s juridical doctrine system. It is stated that the justification of the procedural transition in the principle of the best interests of the child derives from the requirements of the doctrine of margin of appreciation. Under the doctrine of margin of appreciation, the value of procedural transition lies in: First, restricting the room of free discretion of the ECHR to increase certainty and predictability of the principle of the best interests of the child; Second, giving play to the effect of procedural autonomy to achieve distributive justice and corrective justice of judgments; Third, enabling all relevant parties to feel subjective procedural justice to end disputes by giving fair judgments. The legitimacy and value of the procedural transition in the principle of the best interests of the child are as follows:

A. Requirement for legitimacy: doctrine of margin of appreciation

The doctrine of margin of appreciation originated from the principle of subsidiarity of the ECHR, and its norm was established in Protocol No.15 amending the European Convention on Human Rights. 50 It refers to that within the framework of the European Convention on Human Rights, domestic courts of States Parties have the primary responsibility to safeguard human rights, while the ECHR plays an inferior and supplementary role in this regard.51 To be specific, First, the judgments of the ECHR and its interpretations of the European Convention on Human Rights do not have priority and direct binding force for States Parties, which have the right to determine the manner in which the European Convention on Human Rights is implemented in their own countries and have the right not to accept the decisions of the ECHR, which is called “positive subsidiarity.”52 Second, in disputes involving sensitive political, economic, sociocultural, moral and religious issues in States Parties, the ECHR tends to endorse the judgments of domestic courts, which is called “negative subsidiarity.”53 Third, the ECHR does not unprincipledly endorse the judgments by domestic courts of States Parties on the basis of traditional beliefs, but acts as a subsidiary supervisor and will rule that a State Party has violated the European Convention on Human Rights when its judgement clearly violates the minimum standards of the European Convention on Human Rights and disproportionately infringe the basic rights of citizens.54 During the period of the European Commission of Human Rights, including the early years of the ECHR, it was difficult to establish a set of standards to protect the basic rights of citizens applicable to all States Parties due to the considerable differences in their political cultures and legal systems. In this context, how to distribute judicial power between regional and domestic courts became challenging.

The doctrine of margin of appreciation is actually a strategic choice of the ECHR, which helps the ECHR establish a unified human rights review system under different circumstances and conditions of different States Parties, and effectively mediate the contradictions concerning the judicial sovereignty of States Parties and the international jurisdiction of human right.55 Today, through the doctrine of margin of appreciation, the ECHR has expanded its actual powers, becoming the most authoritative and influential regional human rights institution in the world.

When the doctrine of margin of appreciation is applied to cases relevant to children, it will undoubtedly lead to a relaxed application of the principle of the best interests of the child. Substantive review of this principle requires the ECHR to comprehensively examine the legislative, judicial and administrative processes of States Parties, in order to determine in individual cases whether States Parties have applied the principle of the best interests of the child in form and substance. This would undoubtedly challenge the juridical sovereignty and free discretion rights of States Parties. The procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child requires the ECHR to exercise as much restraint as possible, to adopt a relatively passive and conservative position, and to trust States Parties’ judgments on domestic cases. As stated by the ECHR in a case related to a custody dispute, “[The ECHR] fully believes in the domestic court’s professional judgment on specific matters, so the review is confined to examining whether the domestic court exercised its power in a reasonable, prudent and kind manner and whether all reasons and factors put forth by the domestic court are relevant and sufficient.”56Some scholars worry that the doctrine of margin of appreciation may help States Parties evade their international human rights

responsibilities, making the review of the ECHR a mere formality, which is unconducive to the effective protection of human rights.57 For this reason, while the wide margin of appreciation means that States Parties are free to adjust the criteria for the application of the principle of the best interests of the child in individual cases, it does not mean that they have unrestricted discretion within the framework of the European Convention on Human Rights. The semi-procedural review schemes developed by the ECHR, namely key factors-based review and factor list-based review, set considerable qualitative requirements on States Parties to apply the principle of the best interests of the child, and the ECHR is still able to urge States Parties to substantively respect and apply the principle of the best interests of the child through procedural review, in order to strike a balance between the doctrine of margin of appreciation and the effective protection of human rights.

B. Value 1: limiting the role of free discretion

As a substantive right, the biggest problem with the principle of the best interests of the child lies in its conceptual ambiguity and generalization. A legislation document of the United Nations reveals that in the course of discussing the draft of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the representative of Norway expressed worry about the principle of the best interests of the child, saying that the principle was too subjective and general, and its specific contents depend on the interpretation of the parties who apply it.58 Some scholars responded that the principle of the best interests of the child originated from the special protection of children in domestic family laws, and it is impossible to list all the factors related to this principle that need to be considered in family law, so the principle of the best interests of the child can only be generalized and vague in international human rights conventions.59 Therefore, the substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child relies on the free discretion of the judges of the ECHR, which can easily lead to “judicial inertia.”60 The abuse of free discretion has resulted in arbitrariness and inconsistent standards in adjudication, seriously undermining judicial predictability and credibility. Although there are restrictions on the free discretion of substantive review, namely, the application of the proportionality principle in individual cases in order to achieve a balance between the interests of the child and the interests of parents and the public interest, which sets a reasonable boundary for free discretion, such restrictions on free discretion still depend on judges’ personal professionalism to reasonably apply the proportionality principle and interests balancing in individual cases. This, on the other hand, does not help resolve the ambiguity and uncertainty of the principle of the best interests of the child itself.61 Meanwhile, the limitations of substantive legal reasoning methods require judges to adopt legal principles outside the norms to deal with difficult cases, and it is inevitable to fall into the conflict between different legal principles and values, and it is still difficult to fundamentally avoid judges’ subjective value choices and judgments.62 From the position of value relativism, limiting free discretion inevitably requires moving toward procedural restrictions.63

The procedural transition in the principle of the best interests of the child is conducive to limiting judges’ free discretion to achieve both individual justice and universal justice. From the macro perspective of the rule of law, an important role of legal procedures is to restrict arbitrariness. Through the differentiation and independence of power by procedures, it enables procedure participants to cooperate and contain each other after role taking, so as to shrink the room for arbitrariness.64 As for the review of the principle of the best interests of the child, with the holistic review approach, judges only need to apply simple deductive reasoning, i.e. whether a State Party applies the principle of the best interests of the child; According to the key factors-based review scheme or the factor list-based review scheme, after the key factors or the factor lists have been enumerated through summarizing precedents, the judges will compare whether they have been satisfied in a specific case. Abandoning substantive review in favor of procedural review and transforming the complex review methods such as the balancing of interests and the principle of proportionality into the method of deductive reasoning make judges lose much of the free discretion space and ensure the certainty and predictability of adjudication. By limiting the discretion of judges, the boundaries of the principle of the best interests of the child have been stabilized, making it shift from an ambiguous substantive review standard to a procedural review standard with clear contents and criteria in jurisprudence.

C. Value 2: the effect of procedural autonomy

The effect of procedural autonomy, as a dimension of the theory of procedural justice, refers to that once the adjudication of a case is produced through trial procedures, it carries the value of objective procedural justice.65 The theory of procedural justice was put forth by Jeremy Bentham. Bentham upheld the “absolute instrumentalist values” of procedural laws and stressed that procedural laws serve and are subject to substantive laws, with an aim to realize the “greatest wellbeing of most people.”66 This theory was later developed by Cesare Beccaria67 and others. For instance, in the book A Theory of Justice, John Bordley Rawls put forward ideas that went beyond utilitarianism and incorporated procedural value into the system of “justice.” He expounded the theory of procedural justice: Rawls divides procedural justice into three categories — perfect procedural justice, imperfect procedural justice and purely procedural justice. “Perfect procedural justice” should have independent criteria for evaluating justice and procedures to ensure its realization, i.e. when dividing a cake, ensure the person who cut the cake takes the last piece. It requires a perfect combination of means and aims, which is almost impossible in specific juridical practice; “Imperfect procedural justice” has substantive evaluation criteria but lacks procedural guarantees, i.e. most judicial procedures; The ideal judicial procedure should be “purely procedural justice”, that is, there are no independent standards for evaluating whether the judgment is just, and as long as a court trial follows certain procedures, it will definitely result in a just judgment.68 The doctrine of “purely procedural justice” pioneered the procedure-based theory, that is, the procedure itself has the function of achieving distributive justice and corrective justice.69 Although Rawls preferred “pure procedural justice,” he emphasized that whether substantive justice can ultimately be achieved, legal procedures can give litigation participants the opportunity to express justice while respecting the practical needs and values of substantive justice. In this sense, procedural justice is more universally applicable than substantive justice.70

The substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child is what Rawls called “imperfect procedural justice.” Whether the best interests of the child are observed stands for the criterion for justice, and the substantive review process is an “imperfect procedure.” Due to the conceptual ambiguity and uncertainty of the best interests of the child and the excessive free discretion that comes with it, there may be erroneous results and individual human rights cannot be guaranteed even if the judges of the ECHR follow the substantive procedure, i.e. the “legality — purposefulness —necessity in a democratic society” review steps. The procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child is what Rawls called “purely procedural justice.” Regardless of whether State Parties have substantially complied with the principle of the best interests of the child, the ECHR only needs to follow the procedural review steps and use deductive reasoning to determine whether the State Parties apply the principle of the best interests of the child or whether they apply some of the key factors or factor lists therein, the judgments must be just, that is, the State Parties’ procedural compliance (or non-observance) of the principle of the best interests of the child, also known as the effect of procedural autonomy. Scholars often use the term “good process for outcomes”71 when endorsing the procedural transition of the ECHR.

D. Value 3: subjective procedural justice

The core view of the value of subjective procedural justice, also known as “perceptual procedural justice,” is that litigation participants are more concerned about whether the case is handled in a just procedure (perceptual procedural justice) than whether the judgment is fair (distributive justice).72 The value of subjective procedural justice is based on the value of objective procedural justice and summarized by American social psychologists through extensive fieldwork and experimental research: The parties involved are naturally hostile to the legal institutions, and most of them file a lawsuit as the last resort73. If the judicial process is perceived as proper and can alleviate that hostility, and vice versa, it will be deepened. It is necessary to make people feel the fairness and justice of judicature and let them trust legislators, judicial staff and law enforcers, even if the outcomes of the legal process are unfavorable to the parties concerned.74 Upon further enriching and developing the theory of subjective procedural justice, scholars Tyler and Lind summarized four elements that affect the procedural justice perceived by the parties concerned through fieldwork: participation, which ensures litigation participants must have opportunities to express their own views; neutrality, which requires juridical institutions to uphold the principle of neutrality in judgments; respect, which ensures litigation participants feel they are respected and treated seriously in the course of litigation; trust, which requires litigation participants and the juridical system to establish a bond of mutual trust.75 The value of subjective procedural justice does not mean the negation of the value of objective procedural justice but lies in satisfying people’s imagination of fair and just judicial procedures, based on the value of objective procedural justice, so as to eliminate disputes.

The substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child is, to some extent, a “legal black box” for the applicants. With complex and elaborate legal reasoning due to the balance of interests or the proportionality principle, it cannot be understood and interpreted by an applicant without professional training. Moreover, in the course of substantive review, the parties involved do not have opportunities to participate in court hearings other than expressing their appeal opinions. Therefore, the legal proceedings of substantive review are “partially malicious” for the applicants, and it is difficult for the parties involved to feel procedural justice.76 In the procedural review of the principle of the best interests of the child, the ECHR adheres to a position of neutral adjudication and acknowledges that State Parties’ judicial systems are more aware of the affairs taking place in their respective countries under the doctrine of margin of appreciation. The ECHR will not overturn the judgments of domestic courts unless there are sufficient reasons. In addition, procedural review focuses on the applicant’s “participation” in the legal process. Both key factors-based review and factor list-based review regard listening to children’s and parents’ opinions as a factor that must be considered in procedural review, emphasizing the weight of children’s opinions among all factors to be reviewed and stressing that the importance of children’s opinions increases with their growing ages and mental maturity and that simply listening to children’s opinions without giving them priority can also constitute a neglect of the principle of the best interests of the child77. Compared to substantive review, one value of procedural review lies in that the dignity of the applicants can be better respected, with an aim to pursue the value of subjective procedural justice.

V. Conclusion

In the protection of basic rights and human rights, the ECHR increasingly tends to adopt procedural review,78 and the principle of the best interests of the child is a good example. In terms of case numbers, procedural review only covers a few cases related to children, of which purely procedural reviews account for a small proportion while semi-procedural reviews which also focus on substantive review factors, account for the majority. The procedural transition in the principle of the best interests of the child represents a new “possibility” for the ECHR to explore the interpretation and application of this principle. In terms of rights protection methods, the ECHR has developed three review schemes that represent different stages of the development of procedural review — holistic review, key factors-based review, and factor list-based review, which aren’t separated from the criteria for substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child. In terms of rights protection effects, the doctrine of margin of appreciation and the theory of procedural justice provide theoretical endorsement to the legitimacy and value of the procedural transition of the principle of the best interests of the child. China’s judicial practice also faces a dilemma in the interpretation and application of the principle of the best interests of the child. However, the procedural review scheme developed by the ECHR is unlikely to be directly applied in China’s judicial practice: Although procedural justice has been identified as the value and objective of China’s substantive laws and procedural laws,79 another theoretical pillar for the procedural transition of the ECHR — the doctrine of margin of appreciation — has no legal foundation and institutional practice experience in China. The doctrine of margin of appreciation, in nature, is a theoretical mode for juridical power distribution in regional human rights courts and domestic courts. This enables the ECHR to focus on legal review while leaving the duty to review the facts of relevant cases to domestic courts. In China’s litigation system, a similar judicial power distribution mode appears in courts of different levels. Whether in the criminal procedure system or in the civil litigation system, the courts of the second instance have the power to rectify errors in fact identification and applicable laws in the trials of the first instance,80 leaving no space or necessity for the application of the doctrine of margin of appreciation. Therefore, the procedural review developed in the juridical practice of the ECHR can defuse the conceptual ambiguity and uncertainty of the principle of the best interests of the child and provide a new conduit for the principle to be applied in all cases related to children. However, it is worth further discussion and exploration to incorporate procedural review into China’s juridical doctrine system.

* HE Wanyu ( 贺万裕 ), Doctoral Candidate at the Institute for Human Rights, China University of Political Science and Law.

1. CRC, General Comments No. 5, UN Doc. CRC/GC/2003/5, 2003, para. 12.

2. CRC, General Comments No. 14, UN Doc. CRC/GC/2013/14, 2013, para. 6.

3. Article 4 of the “General Provisions” chapter of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors, enacted on June 1, 2021, creatively introduced the “principle of the best interests of minors.” The “principle of acting in the best interests of the minor child” stated in the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China is a localized expression based on China’s national conditions and legal culture and traditions. See Guo Kaiyuan, “The Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China and the Protection of Rights and Interests of Minors,” Journal of Chinese Youth Social Science 1 (2021): 118-125; For instance, the concepts and requirements of the principle of the best interests of the child shall be embedded in the field of criminal procedure law. See Song Yinghui and Li Na, “The Application of the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in Criminal Lawsuits,” Journal of Chinese Youth Social Science 1 (2022): 117-129.

4. Zhang Xuelian, “The Application of the International Covenant on Human Rights in Chinese Courts — From the Perspective of the Provision on the Best Interests of the Child,” Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition) 9 (2018): 19-25; Huang Zhenwei, “On the Application of the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in Judicial Judgments — An Empirical Research Based on 199 Judicial Documents,” Journal of Law Application 24 (2019): 58-69.

5. Liu Zhengfeng, “Balancing the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child and the Protection of Parents’ Human Rights — With Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights as the Research Focus,” Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition) 7 (2015): 17-24; Huang Zhenwei, “On the Application of the Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in Judicial Judgments — An Empirical Research Based on 199 Judicial Documents,” Journal of Law Application 24 (2019): 58-69; Langrogent Fabrice, “The Best Interest of the Child in French Deportation Case Law,” 18 Human Rights Law Review 3 (2018): 567-592; Sandberg Kristen, “The Role of National Courts in Promoting Children’s Rights: The Case of Norway,” 22 International Journal of Children’s Rights 1 (2014): 1-20.

6. For example, the subjective and objective factors for determining the principle of the best interests of the child in cases related to custody disputes. See Xia Jianghao, “The Best Interests of the Child Principle in Residence Disputes after Parental Divorce in China,” Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 2 (2020): 1-11; Zhu Xiaofeng, “Evaluation Norms for the Principle of the Best Interests of Minors in Custody Disputes, Science of Law (Journal of Northwest University of Political Science and Law) 6 (2020): 86-99; For example, the rules on the application of the principle of the best interests of the child in the system of custodian qualification revocation. See Liang Qing and Li Qi, “Thinking on the System of Custodian Qualification Revocation under the Principle of the Best Interests of Minors,” Research on the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency 5 (2017): 25-33; For example, the three-step review approach based on the child theoretical model proposed to evaluate the individual characteristics and needs of children and identify their best interests. See Krutzinna Jenny, “Who is “The Children’s Best Interests and Individuality of Children in Discretionary Decision-Making,” The International Journal off Children’s Rights 1 (2022): 120-145.

7. He Xin, “Preliminary Comparison between Social Sciences of Law and Legal Dogmatics — Starting with the Concept of the Best Interests of the Child,” China Law Review 5 (2021): 154-163; Zhang Xuelian, “The Application of the International Covenant on Human Rights in Chinese Courts — From the Perspective of the Provision on the Best Interests of the Child,” Journal of Guangzhou University (Social Science Edition) 9 (2018): 19-32.

8. CRC, General Comments No. 14, UN DOC. CRC/GC/2013/14, 2013, para. 32.

9. Takács Nikolett, “The Threefold Concept of the Best Interests of the Child in the Immigration Case Law of the ECHR,” 62 Hungarian Journal of Legal Studies 1 (2022): para. 99.

10. Leloup Mathieu, “The Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in the Expulsion Case Law of the European Court of Human Rights: Procedural Rationality as a Remedy for Inconsistency,” 37 Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 1 (2019): 51-68. Sormunen Milka, “Understanding the Best Interests of the Child as a Procedural Obligation: The Example of the European Court of Human Rights,” 20 Human Rights Law Review 4 (2020): 748-751. O’Mahony Conor, Child Protection and the ECHR: Making Sense of Positive and Procedural Obligation,” 27 International Journal of Children’s Rights 4 (2019): 670-671.

11. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights and Council of Europe, Handbook on European Law Relating to the Rights of the Child, 2015, para. 75.

12. Such substantive review procedures for rights are clarified in some provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights, which the ECHR extracts and applies in the substantive review of almost all rights. See Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights: “1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence; 2. There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

13. Zhang Xiang, “Thinking Framework for the Limitations on Basic Rights,” The Jurist 1 (2008): 134.

14. ECHR, Case of Sahou and Pircalab v. Romania, Application no. 46572/99, 2004.

15. ECHR, Case of Uner v. the Netherlands, Application no. 46410/99, 2006.

16. ECHR, Case of Carlson v. Switzerland, Application no. 49492/06, 2008.

17. ECHR, Case of Andersena v. Latvia, Application no. 79441/17, 2020.

18. Liu Zhengfeng, “The Principle of Interests Balancing in Parent-Child Right Conflict Studies Centered around the Cases of the ECHR,” Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition) 5 (2015): 36-39.

19. Kilkelly Ursula, “Protecting Children’s Rights Under the ECHR: the Role of Positive Obligations,” Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 3 (2010): 248-251.

20. For instance, in cases related to deportation, the ECHR has developed three factors in the substantive review of the principle of the best interests of the child, namely, children’s age, their connections with other countries, and their effective familial bonds, which are used to evaluate whether such deportation conforms to the principle of the best interests of the child. See Leloup Mathieu, “The Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in the Expulsion Case Law of the European Court of Human Rights: Procedural Rationality as a Remedy for Inconsistency,” 51-68.

21. Mnookin, Robert, “Child Custody Adjudication: Judicial Functions in the Face of Indeterminacy,” Law and Contemporary Problems 3 (1975): 230.

22. ECHR, Case of Dobbertin v. France, Application no. 13089/87, 1993; ECHR, Case of Mayzit v. Russia, Application no. 63378/00, 2005; ECHR, Case of Jorgic v. Germany, Application no. 74613/01, 2007.

23. Brems Eva and Laviysen Laurens, “Procedural Justice in Human Rights Adjudication: The European Court of Human Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 1 (2013): 190-192.

24. Harvey Darren, “Towards Process-Oriented Proportionality Review in the European Union,” European Public Law 1 (2017): para. 97.

25. Tribe Lawrence, “Structural Due Process”, Harvard Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Law Review 2 (1975): para. 269.

26. Bar-Siman-Tov Ittai, “The Puzzling Resistance to Judicial Review of the Legislative Process,” Boston University Law Review 91 (2011): para. 1961.

27. Cali Basak, “From Flexible to Variable Standards of Judicial Review: The Responsible Domestic Courts Doctrine at the European Court of Human Rights,” in Shifting Centres of Gravity in Human Rights Protection, Rethinking Relationship Between the ECHR, EU, and National Legal Orders, Mjöll Amardótti, Oddnyr and Buyse Antoine (London; New York: Routledge, 2016), 144-160.

28. Sormunen Milka, “Understanding the Best Interests of the Child as a Procedural Obligation: The Example of the European Court of Human Rights,” 20 Human Rights Law Review 4 (2020): 749.

29. Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 17-18.

30. CRC, General Comments No. 14, UN DOC. CRC/GC/2013/14, 2013, para. 6.

31. Leloup Mathieu, “The Principle of the Best Interests of the Child in the Expulsion Case Law of the European Court of Human Rights: Procedural Rationality as a Remedy for Inconsistency,” 56.

32. ECHR, Case of W. v. the United Kingdom, Application no. 9749/82, 1987.

33. ECHR, Case of M. P. E. V. and Others v. Switzerland, Application no. 3910/13, 2014; ECHR, Case of Guliyev and Sheina v. Russia, Application no. 29790/14, 2018; Case of Royer v. Hungary, Application no. 9114/16, 2018.

34. ECHR, Case of Royer v. Hungary, Application no. 9114/16, 2018.

35. Ibid., para. 56-61.

36. Gerards Janeke, “Procedural Review by the ECHR: A Typology,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), para. 159.

37. Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 18.

38. Nussberger Angelika, “Procedural Review by the ECHR: View from the Court,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 180.

39. ECHR, Case of Elita Magomadova v. Russia, Application no. 77546/14, 2018.

40. ECHR, Case of M. and M. v. Croatia, Application no. 10161/13, 2015.

41. The “ultima ratio principle” refers to use something as the last possible resort, method and measure to achieve a certain goal. In this specific case, it refers to whether limiting the rights of the child is the last possible resort and method. See ECHR, Case of D. L v. Bulgaria, Application no. 7472/14, 2016.

42. ECHR, Case of M. and M. v. Croatia, Application no. 10161/13, 2015, para. 176-187.

43. ECHR, Case of Zelikha Magomadova v. Russia, Application no. 58724/14, 2020, para. 114-119.

44. In China, for example, the evaluation of the best interests of the child in custody disputes shall take into account subjective factors such as the will of the parents, minors, and other stakeholders and objective factors such as living environment, economic conditions, parents’ occupations, education, gender, and physical conditions, so as to form a factor list for reviewing the best interests of minors. See Zhu Xiaofeng, “Evaluation Norms for the Principle of the Best Interests of Minors in Custody Disputes,” Science of Law (Journal of Northwest University of Political Science and Law) 6 (2020): 90-94.

45. CRC, General Comments No. 14, UN DOC. CRC/GC/2013/14, 2013, para. 53-79.

46. ECHR, Case of M. L v. Norway, Application no. 43701/14, 2017.

47. Ibid., para. 10-17.

48. Ibid., para. 58.

49. Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 21.

50. “Affirming that the High Contracting Parties, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, have the primary responsibility to secure the rights and freedoms defined in this Convention and the Protocols thereto, and that in doing so they enjoy a margin of appreciation, subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights established by this Convention.” See Council of Europe, Protocol No. 15 amending the Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Council of Europe Treaty Series-No. 213, 2013.

51. Fan Jizeng, “Function and Logic of the Application of the Proportionality Principle by the ECHR,” European Studies 5 (2015): 104.

52. The difference between “postive subsidiarity” and “negative subsidiarity”. See Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 22.

53. Carozza Paolo, “Subsidiarity as a Structural Principle of International Human Rights Law,” The American Journal of International Law 1 (2003): para. 57.

54. Petzold Hebert, The Margin of Application: Interpretation and Discretion Under the European Convention on Human Rights (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing, 2000), 15-21.

55. Fan Jizeng, “Method and Logic of the Application of the Doctrine of Margin of Appreciation by the ECHR,” Southeast Law Review 2 (2016): 98.

56. ECHR, Case of Elita Magomadova v. Russia, Application no. 77546/14, 2018, para. 106.

57. Brauch Jeffrey, “The Margin of Appreciation and the Jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights: Threat to the Rule of Law,” Columbia Journal of European Law 1 (2004-2005): para. 125.

58. United Nations Centre for Human Rights, Legislative History of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1978-1989: article 3 (best interests of the child), HR/1995/Ser. 1/article. 3, para. 26-31.

59. Alston Philip, The Best Interest of the Child: Reconciling Culture and Human Rights (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 1994), 12-13.

60. Eekelaar John, “Beyond the Welfare Principle,” Child and Family Law Quarterly 3 (2002): para. 240.

61. Liu Zhengfeng, “The Principle of Interests Balancing in Parent-Child Right Conflict Studies Centered around the Cases of the ECHR,” Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition) 5 (2015): 43.

62. The method to restrict free discretion through substantive legal reasoning. see Neil MacComick, Legal Reasoning and Legal Theory, translated by Jiang Feng (Beijing: Law Press · China, 2005).

63. The method to limit free discretion through the procedural reasoning theory in the legal argumentation theories see Robert Alexy, Theory of Legal Argumentation, translated by Shu Guoying (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2019).

64. Ji Weidong, “The Importance of Legal Procedures — Another Thinking of the Development of China’s Legal System,” Social Sciences in China 1 (1993): 87-88.

65. Chen Ruihua, “On the Autonomous Value of Procedural Justice — The Role of Procedural Justice in Shaping Judgments,” Jianghuai Tribune 1 (2022): 7.

66. Chen Ruihua, “The Four Modes of the Theory of Procedural Value,” Peking University Law Journal 2 (1996): 2.

67. Cesare Beccaria discussed the value of legal procedures from the perspective of utilitarianism, expounding the “principle of presumption of innocence” and the idea of humanizing criminal procedures and revealing the intrinsic value of criminal procedures themselves. See Cesare Beccaria, On Crimes and Punishments, translated by Huang Feng (Beijing: Peking University Press, 2008).

68. John Bordley Rawls, A Theory of Justice, translated by He Huaihong, etc. (Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 2009), 66-68.

69. Ji Weidong, “The Formality and Substance of Legal Procedure — Taking the Criticism of Procedural Theory and the Proceduralization of Critical Theory as Clues,” Journal of Peking University (Philosophy & Social Sciences) 1 (2006): 118.

70. John Bordley Rawls, Political Liberalism, translated by Wan Junren (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2000), 448-449.

71. Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 18.

72. Guo Chunzhen, “Perceptual Procedural Justice — Subjective Procedural Justice and Its Construction,” Law and Social Development 2 (2017): 106.

73. This can be mutually confirmed by the “disgust to litigation” popular in traditional Chinese society. See Fei Xiaotong, Rural China (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 2008), 70-71.

74. Thibaut, John and Walker Laurens, “Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis,” Duke Law Journal 6 (1977): 1289-1292.

75. Tyler, Tom and Lind, Allan, The Social Phycology of Procedural Justice (New York: Plenum Press, 1988), para. 28.

76. Brems Eva, “The ‘Logics’ of Procedural — Type Review by the European Court of Human Rights,” in Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases, Gerards, Janneke and Brems Eva (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 5-6.

77. ECHR, Case of M. and M. v. Croatia, Application no. 10161/13, 2015, para. 176-187; ECHR, Case of Zelikha Magomadova v. Russia, Application no. 58724/14, 2020, para. 114-119.

78. Gerards Janneke and Brems Eva, Procedural Review in European Fundamental Rights Cases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

79. Chen Ruihua, “Theory of Procedural Justice — An Analysis from the Perspective of Criminal Judgments,” Peking University Law Journal 2 (1997): 69-77; Zhang Weiping, “Basic Modes of Civil Litigation — The Basis for Conversion and Choice,” Modern Law Science 6 (1996): 27; Zhou Youyong, “The Fair Procedure Principle of the Administrative Law,” Social Sciences in China 4 (2004): 115-124.

80. Yi Yanyou, The Criminal Procedure Law: Rules, Tenets and Application (Beijing: Law Press · China, 2019), 563; Zhang Weiping, The Civil Procedure Law (Beijing: Law Press · China, 2019), 379.

(Translated by LI Haile)