The Four Categories of Chinese Discourse on Human Rights and Their Interrelationships

CHANG Jian*

Abstract: In China, the main discourse on human rights can be classified into four categories: political discourse, policy discourse, institutional discourse, and academic discourse. These four categories show significant differences in terms of the context, content, mode of expression, characteristics, and functions of the discourse. They cannot be simply equated or interchangeable with one another. However, they also rely on, restrict, and promote each other, and under certain conditions, they can be transformed into one another. It is needed to prevent imbalances, mismatches in context, isolation, and inadequate translation among human rights discourses. Meanwhile, it is essential to promote balanced development among different discourses, where each discourse maintains its own boundaries, refers to one another, and undergoes accurate translation, in order to construct their healthy interrelationships. Exploring appropriate methods of translation between discourses is an important and worthwhile topic for research in Chinese human rights discourse. It holds significant practical significance and academic value in constructing the Chinese human rights discourse system.

Keywords: political discourse on human rights · policy discourse on human rights ·institutional discourse on human rights ·academic discourse on human rights ·interdiscursivity

During the 37th group study session of the Central Political Bureau in February 2022, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Commitee emphasized that, drawing on China‘s rich experience of advancing human rights, we should formulate new concepts and develop systems of academic discipline, research and discourse.1 To construct a Chinese discourse system on human rights, it is necessary to analyze the discourse structure in the field of human rights, particularly by distinguishing different categories of human rights discourse that exist in reality.

In the statements on human rights in China, various categories of discourse play significant roles, including political discourse, policy discourse, institutional discourse, and academic discourse. They differ significantly in terms of speech context, content, style, characteristics, approaches, and functions. They cannot be simply equated or directly applied to each other, nor can they be isolated from each other without reference. It is important to appropriately distinguish these four types of discourse and explore the intrinsic connections among them in order to construct a synergistic relationship. This is of great significance for promoting and improving the construction of the Chinese human rights discourse system.

I. Differences of the Four Categories of Chinese Discourse on Human Rights

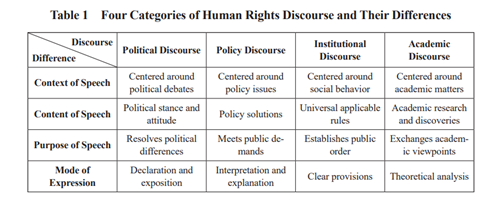

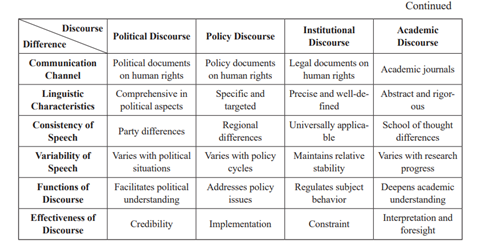

In recent years, the construction of the Chinese human rights discourse system has become a popular research theme in the academic community. However, in existing research, many scholars have treated Chinese Discourse on Human Rights as a general and undifferentiated concept, without specific distinctions among the different types of discourse within Chinese Discourse on Human Rights. This kind of generic conceptualization hinders in-depth research on human rights discourse. To deepen our understanding of the Chinese human rights discourse system, it is essential to differentiate the various categories of discourse it encompasses and clarify the differences among them in terms of context, content, style of expression, modes of communication, discourse functions, and efficacy.

Through meticulous research on various statements on contemporary human rights in China, it can be observed that there are several distinct categories within the human rights discourse. These categories need to be clearly distinguished. Among them, the four most influential categories that have a significant impact on the construction of the human rights system in China are political discourse, policy discourse, institutional discourse, and academic discourse. They differ significantly in terms of the context, content, and purpose of the speech, mode of expression and communication channels, linguistic characteristics, consistency and variability of speech, as well as the functions and effectiveness of discourse. Please refer to Table 1 for more details.

A. Political discourse on human rights

Political discourse on human rights is a type of discourse that involves the speech between political actors. Its discourse context revolves around certain political debates, and its discourse content and purpose involve the expression of political positions and attitudes. The discourse style is declarative and explanatory. The formal channels for expression include political speeches and government-issued political documents, such as various white papers on human rights. Its discourse characteristics include comprehensiveness in political aspects, but there are partisan differences in discourse consistency, and the content of discourse can also change with the political situation. The main function of political discourse on human rights is to promote political understanding in the field of human rights and to build political consensus. Therefore, its discourse effectiveness is mainly reflected in the public credibility of the discourse, i.e., whether it can be understood, recognized, and accepted by the political audience.

Political discourse on human rights can be distinguished into macro, meso, and micro levels based on the degree of specificity in the content it addresses.

Macro-level political discourse on human rights is primarily used to express political positions and attitudes toward human rights. Examples include statements like The enjoyment of full human rights has been the long-standing ideal pursued by humanity, The greatest human right is the happiness and well-being of the people, We adhere to a people-centered human rights concept, and We are comprehensively advancing the development of human rights in China.

Meso-level political discourse on human rights is focused on articulating the fundamental principles in the field of human rights. Examples include statements such as The Party and the government regard respecting and protecting human rights as an important principle in governance, We ensure that the people enjoy extensive rights and freedoms according to the law, and China adheres to the combination of the universality principle of human rights and the contemporary reality, and follows a path of human rights development that suits its national conditions.

Micro-level political discourse on human rights is used to highlight the strategic priorities in protection of human rights. Examples include statements like The rights to survival and development are fundamental and paramount human rights, We guarantee the equal participation and development rights of all members of society in accordance with the law, We strengthen the rule of law in protecting human rights, and People's democracy is a kind of whole-process democracy.

B. Policy discourse on human rights

Policy discourse on human rights refers to the discourse used between entities of policy relations. It is shaped by the context of policy debates, and its content revolves around policy solutions. Its purpose is to meet public demands, while it employs explanatory and descriptive approaches to articulate policy intentions and justifications. The formal channels for expressing are policy-oriented documents issued by the government, such as national action plans on human rights and various policy documents related to human rights. Its discourse characteristics include clear targeting, regional variations in linguistic consistency, and changes in discourse content corresponding to different stages of the policy cycle. The main function of policy discourse on human rights is to address policy issues, and therefore, its discourse effectiveness is primarily reflected in the execution of discourse, which refers to the feasibility and expected implementation outcomes of the policy proposals.

Policy discourse on human rights can also be categorized into macro, meso, and micro levels based on the level of specificity in its content.

Macro-level policy discourse on human rights is primarily used to articulate policy principles and goals. Examples include statements such as Consolidate the achievements in poverty alleviation, promote rural revitalization, prioritize employment policies, implement the Healthy China Initiative, improve the social security system, promote fair development of education, strengthen public cultural services, promote common prosperity for all people, and protect citizens economic, social, and cultural rights, or The state will continue to strengthen the construction of democratic rule of law, improve democratic institutions, enrich democratic forms, broaden democratic channels, strengthen protection of human rights in administrative law enforcement and the judiciary, and enhance the protection of citizens rights and political rights, or The state will take measures to further protect the rights and interests of ethnic minorities, women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities.

Meso-level policy discourse on human rights is primarily used to articulate policy projects and their main contents. For example, statements may include Fully implement the employment priority policy, eliminate employment and occupational discrimination, improve wage and welfare systems, establish a sound labor relationship coordination mechanism, implement safety production management systems, and strengthen the supervision of labor law implementation, or Adhere to the principle of ensuring basic social security for all, and the requirements of ensuring a safety net, weaving a dense network, and establishing mechanisms, and accelerate the establishment of a multi-level social security system that covers the entire population, coordinates urban and rural areas, is fair and unified, and sustainable.

Micro-level policy discourse on human rights is used to elaborate on specific requirements and indicators of policies. Examples include Complete the inspection and rectification of safety hazards in rural housing within about three years, Keep the urban unemployment rate manageable within 5.5%, or Pay part or all of the premiums for individuals facing difficulties in paying contributions for urban and rural residents pension insurance, or Extend the age of coverage for the assistance and support of extremely poor minors from 16 to 18 years old.

C. Institutional discourse on human rights

Institutional discourse on human rights is the discourse among legal entities in the context of legal relationships. It revolves around various social behaviors, addressing universally applicable rules of conduct. The purpose of this discourse is to establish public order, and it does so by making explicit provisions. The formal channel of expression for this discourse is through human rights legal documents, including the Constitution and various laws and regulations. The characteristics of institutional discourse include precise definition, universal applicability, and relative stability. The primary function is to regulate the behavior of entities, and its effectiveness is manifested in the sufficient constraints it imposes on relevant entities and the expected effects it produces within the specified time period.

Institutional discourse on human rights can also be divided into macro, meso, and micro levels based on the level of specificity in its content.

Macro-level institutional discourse on human rights is primarily used to articulate the fundamental principles that institutional norms on human rights must adhere to. Examples of such principles include the state shall respect and protect human rights, all citizens are equal before the law, every citizen enjoys the rights prescribed by the Constitution and laws and must fulfill the obligations stipulated by the Constitution and laws, and the personal rights, property rights, and other lawful rights and interests of civil subjects are protected by law, and no organization or individual shall infringe upon them.

Meso-level institutional discourse on human rights is mainly used to describe the specific rights established by the human rights system. Examples of such rights include the protection of citizens personal rights, property rights, democratic rights, and other rights, natural persons rights to life, bodily integrity, health, name, portrait, reputation, honor, privacy, and the right to marriage based upon the complete willingness of both man and woman, and the defendant's right to legal representation.

Micro-level institutional discourse on human rights is primarily used to articulate the specific content and requirements of individual rights. Examples include the right of a criminal suspect to appoint defense counsel, litigation participants have the right to file complaints against judges, prosecutors, and investigators for infringement of citizens litigation rights and personal insults, and criminal suspects and defendants have the right to meet with duty lawyers, personality rights refer to the rights of civil subjects, including the rights to life, bodily integrity, health, name, title, portrait, reputation, honor, and privacy, and natural persons have the right to privacy, and no organization or individual shall invade others privacy through means such as prying, harassment, disclosure, or public exposure. Privacy encompasses the private tranquility of an individual's personal life and the intimate spaces, activities, and information that they do not wish others to know about.

D. Academic discourse on human rights

Academic discourse on human rights refers to the discourse between academic entities, focusing on the relationships between academic viewpoints. The discourse context revolves around academic issues related to human rights, and the content involves scholars academic perspectives, research findings, and theoretical constructions. The purpose of this discourse is to exchange academic viewpoints and deepen the academic understanding of human rights. The model of discourse is through theoretical analysis and rigorous argumentation. The formal expression channel is academic journals, such as human rights journals and human rights blue paper publications. The language used in this discourse is characterized by abstract precision. There are variations in discourse due to different schools of thought and it evolves as research progresses. The primary function of academic discourse on human rights is to deepen academic understanding. Its effectiveness lies in the explanatory power and predictive power of the discourse, namely, whether it can provide reasonable and consistent explanations of human rights phenomena and make valid predictions about the development of human rights.

Academic discourse on human rights can also be classified into macro-level, meso-level, and micro-level discourse based on the level of specificity of the content.

Macro-level academic discourse on human rights is mainly used to articulate various theories of human rights, such as human rights law, human rights politics, human rights sociology, liberal theories of human rights, development-oriented theories of human rights, capability-based theories of human rights, and prepayment perspectives on human rights.

Meso-level academic discourse on human rights is primarily used to describe the categories, characteristics, and research methods of rights, such as positive rights, negative rights, three generations of human rights, research paradigms of human rights, the universality and particularity of human rights, and the absoluteness and relativity of human rights.

Micro-level academic discourse on human rights is mainly used to describe the relationships between various concepts related to human rights and empirical research findings. Examples include the relationship between the protection of basic civil rights and human rights guarantees, the application of the term human rights in judicial reasoning, and the logic behind the formation of international human rights mechanisms.

II. Interrelationships Among the Four Categories of Human Rights Discourse

Although the four types of human rights discourse have significant differences in various aspects, they are inherently interconnected. They depend on, constrain, and promote each other, and under certain conditions, they can be transformed into one another.

A. Interdependence, constraint, and promotion among the four categories of human rights discourse

There is a relationship of mutual dependence, mutual constraint, and mutual promotion among human rights discourses. From the perspective of the actual construction process of the Chinese Discourse on Human Rights, it often begins with a breakthrough innovation emerging from the extensive debates within the academic discourse on human rights. This is followed by the formal construction of political discourse on human rights, and then the corresponding policy discourse on human rights emerges. After thorough deliberation and rigorous argumentation within the academic discourse on human rights, the construction of institutional discourse on human rights is finally initiated.

Firstly, in terms of the relationship between political discourse on human rights and policy discourse on human rights, as well as institutional discourse on human rights, there exists a mutual dependency. On the one hand, the policy discourse and the institutional discourse rely on the support of the political discourse. In China, if the policy discourse fails to gain endorsement from the political discourse, it will lose its political foundation for discourse and its effectiveness in implementation. Similarly, if the institutional discourse does not receive endorsement from the political discourse, it will lack the necessary political conditions to exert its influence, leading to a weakened capacity for effective constraints and an inability to achieve the intended effects. On the other hand, the political discourse needs to be reflected in the policy discourse and the institutional discourse. If the content of political discourse on human rights cannot be successfully transformed into the policy discourse and the institutional discourse, it will become hollow political slogans and lose credibility.

Secondly, the relationship between policy discourse on human rights and institutional discourse on human rights can be characterized by constraint and complementarity. On the one hand, policy discourse on human rights is constrained by institutional discourse on human rights. Institutional discourse on human rights articulates the fundamental principles of protection of human rights, emphasizing consistency, universality, and stability. Policy discourse on human rights must not contradict institutional discourse on human rights. If it contradicts the principles of institutional discourse on human rights, policy discourse on human rights loses its lawfulness. On the other hand, policy discourse on human rights serves as an important complement to institutional discourse on human rights. Institutional discourse on human rights primarily addresses universal and stable human rights issues, while policy discourse on human rights focuses on specific and context-dependent human rights matters. Those temporary or localized human rights issues become the subject of policy discourse on human rights. Additionally, in the process of China s reform, policy discourse on human rights often serves as the precursor to constructing an institutional discourse on human rights. In order to explore the feasibility of constructing an institutional discourse on human rights, relevant policy discourse on human rights usually emerges first. When the policy discourse demonstrates stable implementation and sustained effectiveness, it possesses the conditions to transition into an institutional discourse on human rights.

Thirdly, looking at the relationship between the academic discourse on human rights and political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights, there exists a mutual dependence and mutual promotion. Academic discourse on human rights needs to study political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse. If the academic discourse completely detaches itself from the study of other discourses, it will become like a stream without sources and a tree without roots, isolated from the practical context of human rights, and unable to have an impact on reality. On the other hand, political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights, along with their interrelationships, need to be clarified and examined through academic discourse on human rights. The lack of clarification and examination through academic discourse on human rights can lead to various confusions among other discourses. Furthermore, without the academic discourse, there is a risk of misinterpretation and misuse of the content expressed in each discourse. Moreover, the innovation in academic discourse on human rights often inspires the construction of other discourses. The analytical and argumentative contributions of academic discourse on human rights also provide a theoretical foundation for the construction of other discourses.

In academic research on human rights in China, a significant amount of interpretation is devoted to the political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights. In the interpretation of political discourse on human rights, many recent academic articles have explored General Secretary Xi Jinping s discourse on human rights, particularly his emphasis on the human rights concept of placing the people at the center, adhering to the path of human rights development in China, and upholding the correct understanding of Chinese human rights. These articles provide theoretical analyses to clarify the implications and objectives of political discourse on human rights and systematically analyze various human rights white papers issued by the government. Regarding the interpretation of policy discourse on human rights, numerous academic articles in recent years have examined the significance of policies such as the construction of a moderately prosperous society, poverty alleviation, anti-corruption efforts, and environmental protection in relation to protection of human rights. These articles highlight the importance of national human rights action plans and policies in protecting human rights. In the interpretation of institutional discourse on human rights, a substantial number of academic articles have focused on the significance and role of the Constitution, Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure Law, Civil Code, and other relevant laws in protecting the rights of minority groups, women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities. Meanwhile, the analysis of the limitations of Western liberal human rights theories and the proposition of development-oriented human rights theories have provided inspiration for the construction of political discourse and policy discussion on human rights in China. Reflection within the Chinese academic community on the effectiveness of China's system for protection of human rights has also contributed to the updating and improvement of laws on protection of human rights in China.

B. Mutual conversion among the four categories of human rights discourse

The four types of human rights discourse rely on, constrain, and promote each other, and can undergo mutual conversion under certain conditions.

Firstly, academic discourse on human rights can be transformed into political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights under certain conditions. For example, the academic discourse in the academic community discussing the foundational status of the right to life and the right to development within the human rights framework can be translated into political discourse as to give priority to the people's right to existence and development 2 in the human rights white papers published by the Chinese government. For another example, the academic discourse in the academic community on the importance of economic development as a crucial condition for realizing human rights is translated by the government into policy discourse such as promoting human rights through development. Similarly, the academic discourse on whether criminals are entitled to human rights is translated into institutional discourse in the amendment of criminal procedural law, as seen in phrases like people's courts, people's procuratorates, and public security organs shall guarantee the suspects, defendants, and other participants in litigation the right to defense and other procedural rights as provided by law. 3 The academic discourse on the Principle of Legality is translated into institutional discourse in the Criminal Procedure Law as no one shall be found guilty without a lawful judgment by a people's court.4 The academic discourse on the presumption of innocence and the principle of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is translated into institutional discourse in the Criminal Procedure Law as if the evidence is insufficient to establish the guilt of the defendant, a verdict of not guilty shall be rendered on the ground of insufficient evidence and the crime charged shall not be established. 5

Secondly, political discourse on human rights can be transformed into policy discourse, institutional discourse, and academic discourse on human rights under certain conditions. For example, in the human rights white paper, there is a political discourse stating that the right to survival and development is a primary and fundamental human right. In the Human Rights Action Plan of China (2021-2025), it is translated into policy discourse as China will work to promote common prosperity for its people and protect their economic, social and cultural rights through the following: consolidating its achievements in poverty alleviation, carrying out the strategy of rural revitalization, prioritizing employment, implementing the Healthy China Initiative, improving the social security system, promoting equal access to education, and improving public cultural services. 6 The political discourse on human rights found in speeches by national leaders and human rights white papers, which emphasizes ensuring that the people enjoy extensive rights and freedoms in accordance with the law, is translated into institutional discourse as the state shall respect and protect human rights in the constitution. In the Criminal Procedure Law, it is translated into institutional discourse as protecting citizens personal rights, property rights, democratic rights, and other rights.

III. Misalignment and Restoration of Relations Among Human Rights Discourses

The four types of human rights discourse serve their purposes and depend on, constrain, and promote each other. They can also undergo mutual conversion under certain conditions. However, if the relationships among these discourses are mishandled, it can disrupt the harmonious relationship and prevent each type of human rights discourse from functioning properly.

A. Issues in the four categories of chinese discourse on human rights

Examining the practice of contemporary Chinese Discourse on Human Rights, we can identify four issues: imbalanced development, contextual mismatch, discourse isolation, and inappropriate conversion.

1. Imbalanced development

From the development of various types of human rights discourse in contemporary China, it can be observed that political discourse on human rights has received initial attention. The release of the white paper entitled Human Rights in China in 1991 was a significant milestone in the construction of political discourse on human rights in China. It explicitly declared China s political stance on human rights issues. As of September 2022, the Chinese government has published a total of 85 white papers related to human rights, including 14 comprehensive human rights white papers and 71 thematic human rights white papers, averaging about 2.6 publications per year.

The establishment of the Chinese Journal of Human Rights in 2001 and The Journal of Human Rights in 2002 were significant watershed in the construction of the academic discourse on human rights in China. These professional journals provided platforms for human rights scholars to discuss academic issues related to human rights. In 2011, the publication of the Annual Report on China's Human Rights (The Blue Book) further gathered the summaries and analyses of human rights scholars on the development and practice of human rights in China. In recent years, there have also been the quarterly Chinese Journal of Human Rights, the Journal of Human Rights Law, and other specialized academic journals, which have provided additional professional platforms for the expression and construction of the academic discourse on human rights.

In 2004, the provision of respecting and protecting human rights was included in the Chinese Constitution, marking an important milestone in the construction of institutional discourse on human rights. Based on this constitutional principle, China has subsequently formulated and revised a series of laws and regulations related to human rights, establishing a preliminary legal framework for the protection of human rights in China.

In 2009, the Human Rights Action Plan of China (2009-2010) was stipulated and published, marking a significant milestone for the construction of policy discourse on human rights in China and its systematization. As of 2021, China has formulated, published, and implemented four national action plans on human rights. Additionally, China has developed a series of specialized policy plans for protection of human rights, including the rural poverty alleviation outline, relocation plan for poverty alleviation, rural drinking water safety project plan, social security plan, healthcare development plan, education development plan, cultural development plan, ecological environment protection plan, women s development outline, children s development outline, action plan against trafficking of women and children, aged care development outline, and disabled persons development outline.

However, from an overall development perspective, political discourse on human rights tends to be stronger while other types of human rights discourse are relatively weaker. The establishment of political discourse receives high attention from the authorities, with clear emphasis and vigorous development momentum, and it is frequently used. In comparison, in the realm of policy discourse, although the government has formulated and implemented numerous policies related to protection of human rights, many of these policies do not explicitly link to human rights discourse. Similarly, many institutions related to protection of human rights do not adopt human rights discourses. In the realm of academic discourse, the development space for academic discourse on human rights in China has been relatively limited, lacking a systematic and theoretical academic discourse on human rights. For example,in recent years, there has been a significant amount of innovation in political discourse on human rights. Examples include the right to survival and development is the fundamental human right, ensuring the equal participation and development rights of all members of society in accordance with the law,there is no best human rights, only better ones, the people's well-being is the greatest human right, adhering to the concept of human rights centered on the people, respecting and guaranteeing human rights as an important principle of governance, and people's democracy is a kind of whole-process democracy. However, there has been a relative lack of innovation in academic discourse on human rights, with only sporadic innovative academic discourses such as development-oriented human rights theory and prepayment perspectives on human rights. This imbalance in the development of discourse is a significant factor contributing to a series of problems.

2. Contextual mismatch

Different categories of human rights discourse should be applied in different discursive contexts to effectively fulfill their functions. However, in the actual practice of human rights discourse, there is a significant amount of misalignment between discourse and context, where various types of human rights discourse are used in contexts that are not suitable for their nature.

Firstly, in the context that requires addressing human rights policy issues, there is a need for policy discourse on human rights that is targeted and effective in formulating policies. However, there is often a misalignment where political discourse on human rights, which is more suitable for expressing political positions and attitudes, is used instead. For example, when formulating specific policies to promote the protection of political rights, if only political discourse such as strengthening socialist democratic politics or improving the level of protection of political rights is used without including policy discourse such as promoting political information transparency, incorporating political consultation into decision-making processes, soliciting public opinions on major policy measures, establishing channels for the expression of demands through dedicated hotlines, online petitions, or proxy representation in grievances, and improving the system of designated supervisors, then the expression of such policies on protection of human rights would appear empty and insincere.

Secondly, in contexts that require the establishment of institutional norms for human rights, it is necessary to use institutional discourse on human rights that has precise definitions and strict consistency. However, there is a tendency to utilize political discourse on human rights, which is more suitable for expressing political positions and attitudes, or policy discourse on human rights that varies with policy cycles. For example, if only political discourses such as placing respect and protection of human rights in a more prominent position in the construction of a socialist rule of law country, ushering in a new era of human rights rule of law in China, or ensuring that the people perceive fairness and justice in every judicial case is used to express the system for protection of human rights, or if only policy discourses such as improving legislation in the field of economic, social, and cultural rights, strengthening legislation in the field of civil and political rights, or enhancing legislation to protect the rights of specific groups are employed, without using institutional discourse on human rights that includes statements like abolishing the reeducation through labor system, legally guaranteeing lawyers rights to information, application, appeal, as well as the right to meet, review documents, collect evidence, ask questions, cross-examine, and debate, or providing economic support to crime victims who have been harmed but cannot obtain effective compensation, the portrayal of the system for protection of human rights would appear vague and lack substantive content.

Thirdly, in the context of academic exploration of human rights, it is necessary to employ academic discourse on human rights, which entails theoretical abstraction and analytical frameworks. However, some are inappropriately using political discourse on human rights to express political stances, policy discourse on human rights to present policy proposals, and institutional discourse on human rights to articulate codes of conduct. For instance, some scholars, in their efforts to construct theoretical frameworks for human rights, often rely solely on political assertions expressed through political discourse on human rights found in government white papers, as well as policy goals and measures articulated through policy discourse on human rights in national human rights action plans. However, they fail to incorporate the analytical rigor of academic discourse on human rights, which limits their research outcomes to political declarations and practical work summaries, preventing them from reaching the level of genuine theoretical research.

Lastly, in contexts where it is necessary to articulate political positions and perspectives on human rights, it is appropriate to utilize political discourse on human rights, which is suited for expressing political stances. However, abstract academic discourse on human rights or specific policy discourse on human rights is used in reality. For instance, when expressing the political aspirations on human rights of the Party, the state, or the government, focusing extensively on the theoretical origins of human rights, scholarly debates, and semantic definitions, while neglecting the declaration of political positions, political perspectives, political concerns, and political inclusiveness, would limit the political expression of human rights and make it overly pedantic.

In reality, the phenomenon of directly applying political discourse on human rights to other contexts of human rights discourse is quite common. This leads to a lack of specific direction in policy discourse on human rights, an absence of clear delineation in the institutional discourse on human rights, and a lack of academic depth in academic discourse on human rights. As a result, these discourses lose their intended functions. On the other hand, political discourse on human rights becomes an empty slogan lacking policy and institutional references, which weakens its political credibility and persuasive power.

Besides, there is another kind of context mismatch worth noting, which is the use of human rights discourse in contexts that do not involve human rights issues, or the omission of human rights discourse in contexts that do involve human rights issues. For example, general economic development and improvement in people s living standards, in a broad sense, do not directly address protection of human rights. If they are indiscriminately categorized as human rights discourse without analysis, it may lead to what some human rights scholars refer to as human rights inflation. As public awareness of human rights continues to grow, it is particularly important to pay attention to the misuse of human rights discourse in contexts where human rights issues are not involved. In the long term, such a situation can have serious political and social consequences. In another case, the establishment of democratic systems in China serves as a safeguard for citizens democratic rights; China's poverty reduction practices are specific measures to ensure the survival and development rights of impoverished populations; the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic involves crucial measures to protect citizens right to health. In such contexts, if only general policy discourse is used to express these initiatives without employing policy discourse on human rights, the human rights significance of these policies may not be adequately conveyed.

3. Discourse isolation

On the contrary to misalignment with the discourse context, discourse isolation is characterized by different categories of human rights discourse being fragmented and disconnected from one another. As mentioned earlier, although there are distinctions among the four types of human rights discourse, there still exists an inherent connection among them, with mutual dependence, mutual constraint, mutual promotion, and occasional conversion under certain conditions. However, in reality, many proponents of human rights discourse excessively emphasize the differences between different categories of human rights discourse, disregarding their intrinsic connections and resulting in the isolation of each discourse from one another. For example, some constructions and expressions of political discourse on human rights do not consider whether they can be transformed into specific policy discourse and institutional discourse, resulting in being narrow-minded and isolated. Similarly, many constructions and expressions of policy discourse and institutional discourse on human rights do not reference political discourse on human rights. As a result, numerous policies on protection of human rights and institutional arrangements are not aligned with the political discourse of respecting and protecting human rights. This situation hampers their connection and leads to the violation of the political requirements of respecting and protecting human rights during the implementation of many beneficial policies for the country and the people. Furthermore, some academic discourse on human rights completely isolates itself from political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights, engaging in self-appreciation. On the other hand, the construction of certain political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse does not take into account the academic clarification and refinement conducted by the academic discourse on human rights, resulting in numerous logical loopholes and attracting criticism.

4. Inappropriate conversion

Different types of human rights discourse can be mutually transformed under certain conditions. However, when engaging in discourse conversion, it is crucial to consider the differences between different types of discourse. Otherwise, there may be a misalignment in the process of conversion. Conversely, the same principle applies. For example, the statement individuals are the subjects of human rights is a typical expression in the institutional discourse on human rights. However, if it is transformed into the human rights concept centered around individuals in political discourse on human rights, it can lead to serious political issues. Another example is the phrase life first, which is a typical expression of political attitude and values in political discourse on human rights. However, if it is transformed into epidemic prevention first in policy discourse on human rights, it can lead to serious deviations in policy formulation and implementation. Another example is the phrases building a harmonious society, promoting social harmony, and harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, which are political and policy discourses. If they are directly transformed into the right to harmony in institutional discourse, it can create a series of challenging issues regarding rights and obligations that are difficult to resolve. Similarly, the statement the people's well-being is the greatest human right is a typical example of political discourse on human rights. If it is simply transformed without analysis into the right to well-being or similar language in the institutional discourse on human rights, it may lead to numerous human rights obligations that cannot be effectively addressed or fulfilled.

B. Building a complementary and synergistic relationship among human rights discourses

Building a complementary and synergistic relationship among human rights discourses is of paramount importance in constructing and improving the Chinese human rights discourse system. The concept of a complementary and synergistic relationship among human rights discourses means ensuring the balanced development of the four types of human rights discourses, allowing them to occupy their respective positions, mutually reinforcing each other, and facilitating precise transitions.

Firstly, it is important to promote the balanced development of the four categories of human rights discourse, particularly focusing on promoting the development of policy discourse on human rights, institutional discourse on human rights, and academic discourse on human rights. One crucial condition for promoting the balanced development of these different types of human rights discourse is to adopt appropriate promotion strategies corresponding to each category. It is not sufficient to apply the same approach used for promoting one type of human rights discourse indiscriminately to the development of other types. For example, the development of political discourse on human rights requires support from the political leadership, while the development of policy discourse on human rights necessitates broad public participation. The development of the institutional discourse on human rights relies on careful deliberation by legislative experts, and academic discourse on human rights thrives through scholarly debates. Therefore, it is essential to adopt appropriate promotion strategies based on the specific conditions required for the existence and development of each category of human rights discourse.

Secondly, it is important to adopt the appropriate human rights discourse based on different contexts. Different discourse contexts have different requirements for human rights discourse, and mismatched contexts can hinder the effective functioning of human rights discourse, failing to achieve the intended communicative effects. There are several reasons for the occurrence of mismatched human rights discourse in discourse contexts. Apart from the inadequate development of certain categories of human rights discourse and the mismatched demands placed on human rights discourse within specific contexts, the cross-discourse speaking by the speakers is also an important contributing factor. Therefore, it is essential not only to actively promote the balanced development of various types of human rights discourse and avoid making demands on human rights discourse that are mismatched with the context, but also to ensure that the speakers of human rights discourse stay within their respective domains and avoid context mismatch caused by cross-discourse human rights discourse.

Thirdly, we should promote the mutual reference of human rights discourse. Human rights discourse also exhibits interdiscursivity , which includes inter-symbolic, inter-subjective, and inter-contextual aspects. Different types of human rights discourse derive their relative meanings through the mutual reference of discourse symbols, speaking subjects, and discourse contexts of different categories. Therefore, although the four types of human rights discourse are distinct, they need to understand, inspire, support, and complement each other, rather than working in isolation, speaking their own language, and becoming disconnected from one another.

Finally, promoting accurate conversion between human rights discourses is crucial. The mutual referencing of human rights discourses does not mean simply applying one category of human rights discourse to another. Instead, it requires precise conversion based on the specific requirements of different categories of human rights discourses. Translators need to have a clear understanding and grasp of the characteristics of the discourse being translated and the discourse being translated into. For example, when translating academic discourse on human rights into the political discourse on human rights, it is essential to clarify the political standpoint. When translating political discourse on human rights into policy discourse on human rights, the feasibility of the policy must be considered. When translating political discourse and policy discourse on human rights into the institutional discourse on human rights, the applicability, universality, and stability of the institutions must be taken into account. On the other hand, when translating political discourse, policy discourse, and institutional discourse on human rights into academic discourse on human rights, the underlying theoretical foundations that permeate it must be considered. For example, in political discourse on human rights, the statement the right to survival and development is the primary basic human right would need to be translated in policy discourse on human rights as prioritizing the promotion of the right to survival and development in the human rights development strategy. In the institutional discourse on human rights, it would require a further transformation into effectively guaranteeing the rights to basic living standards, health, social security, education, employment, participation, etc., for citizens. Another example is the statement in political discourse on human rights, The happiness of the people is the greatest human right. In policy discourse on human rights, it would be translated as the sense of achievement, happiness, and security of the people are important indicators for assessing the realization of human rights. In the institutional discourse on human rights, it would be further transformed into everyone has the right to pursue happiness.

Accurate conversion of different types of human rights discourse relies on specific mechanisms tailored to each category. The conversion of academic discourse on human rights should be based on academic research institutions for human rights, such as the China Society of Human Rights Studies. The conversion of institutional discourse on human rights should rely on dedicated legislative bodies, such as specialized committees within the National People s Congress that deal with human rights issues. The conversion of policy discourse and political discourse on human rights should rely on human rights-related departments established by the Party Central Committee or the State Council.

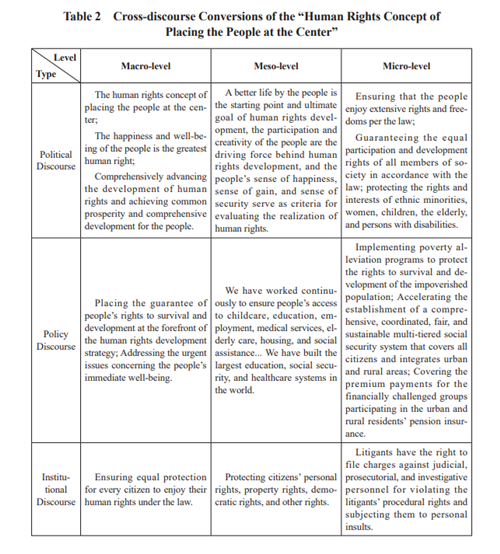

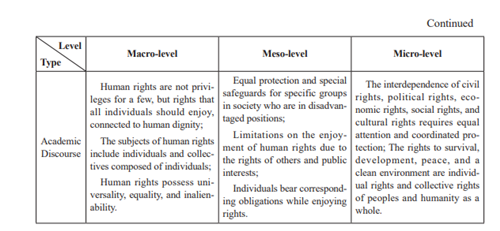

C. Cross-discourse conversions of human rights discourses: taking placing the people at the center as an example

To further illustrate the conversion between different types of human rights discourses, this article takes The human rights concept of placing the people at the center as an example and attempts to analyze how it can be translated into policy discourse, institutional discourse, and academic discourse on human rights. Details are provided in Table 2.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the concept of placing the people at the center has been put forward as a guiding ideology in the development of socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era, representing the core values and direction of Xi Jinping's Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. The human rights concept of placing the people at the center is a specific embodiment of this ideology in the field of human rights, which is also a macro-level political discourse. In the macro-level political discourse, this concept is further expressed as the happiness and well-being of the people is the greatest human right and comprehensively advancing the development of human rights and achieving common prosperity and comprehensive development for the people. At the meso level, it can be further interpreted based on the development concept of development for the people, relying on the people, and sharing the fruits of development with the people. This interpretation highlights that the pursuit of a better life by the people is the starting point and ultimate goal of human rights development, the participation and creativity of the people are the driving force behind human rights development, and the people s sense of happiness, sense of gain, and sense of security serve as criteria for evaluating the realization of human rights. At the micro level, this concept is more specifically expressed as ensuring that the people enjoy extensive rights and freedoms in accordance with the law, guaranteeing the equal participation and development rights of all members of society in accordance with the law, and protecting the rights and interests of ethnic minorities, women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities.

In terms of policy discourse, the interpretation should be based on policy orientation and more specific policy arrangements. At the macro level, it can be expressed as placing the guarantee of people s rights to survival and development at the forefront of the human rights development strategy and addressing the urgent issues concerning the people’s immediate well-being. At the meso level, it is further elaborated in the report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China as worked continuously to ensure people's access to childcare, education, employment, medical services, elderly care, housing, and social assistance... We have built the largest education, social security, and healthcare systems in the world. At the micro level, it should include more specific policy measures such as implementing poverty alleviation programs to protect the rights to survival and development of the impoverished population and accelerating the establishment of a comprehensive, coordinated, fair, and sustainable multi-tiered social security system that covers all citizens, integrates urban and rural areas. Additionally, it can include specific measures such as covering the premium payments for the financially challenged groups participating in the urban and rural residents pension insurance.

Using institutional discourse to translate the concept should consider its universality and feasibility from a regulatory perspective. At the macro level, it can be translated as ensuring equal protection for every citizen to enjoy their human rights under the law. At the meso level, it can be further specified as protecting citizens personal rights, property rights, democratic rights, and other rights. At the micro level, it requires more specific articulation, such as litigants have the right to file charges against judicial, prosecutorial, and investigative personnel for violating the litigants procedural rights and subjecting them to personal insults.

Using academic discourse to analyze and explain this concept requires adhering to the basic paradigms of academic discourse. At the macro level, it can be expressed as human rights are not privileges for a few, but rights that all individuals should enjoy, connected to human dignity, the subjects of human rights include individuals and collectives composed of individuals, human rights possess universality, equality, and inalienability, and so on. At the meso level, it would involve concepts such as equal protection and special safeguards for specific groups in society who are in disadvantaged positions, limitations on the enjoyment of human rights due to the rights of others and public interests, and individuals bearing corresponding obligations while enjoying rights. At the micro level, it would encompass ideas like the interdependence of civil rights, political rights, economic rights, social rights, and cultural rights, requiring equal attention and coordinated protection, and the rights to survival, development, peace, and a clean environment are individual rights and collective rights of peoples and humanity as a whole.

In conclusion, the construction of a human rights discourse system must take into account the differences and interrelationships among different discourses, and strive to build a complementary and synergistic relationship among them, promoting the coordinated development of various human rights discourses.

(Translated by LI Donglin)

* CHANG Jian (常健), Director of the Centre for the Study of Human Rights (National Human Rights Education and Training Base) at Nankai University, Professor at the Zhou Enlai School of Government Management, Nankai University. This article represents a phased outcome of the research project Research on the Practice of Human Rights in China Promoting and Enriching Shared Values for All Humanity funded by the National Social Science Fund of China under project approval No. 22ZDA127.

1. Xi Jinping, “Steadfastly Following the Chinese Path to Promote Further Progress in Human Rights,” Qiushi 12 (2022): 9.

2. The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China, Progress in China's Human Rights (White Paper) (Beijing: People‘s Publishing House, 1995), 1.

3. Article 14 of Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China.

4. Article 12 of Criminal Procedure Law of the People‘s Republic of China.

5. Article 200 (3) of Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China.

6. The State Council Information Office of the People‘s Republic of China, Human Rights Action Plan of China (2021-2025) (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 2021), 5.